Most of us by now are familiar with how our national press and media worked to shape public opinion immediately after both the police assault on picket lines at Orgreave Colliery in 1984 that resulted in niney-five charges of riot being made against striking miners, and the death of ninety-six football supporters in the Hillsborough Stadium in 1989 that resulted in fans being accused of drunkenness and hooliganism, with neither injustice having subsequently led to a single policeman or politician being convicted of a crime. Since the Grenfell Tower fire officially left seventy-two people dead in June 2017, only six people have been convicted of criminal offences, and that for varying degrees of indecent or fraudulent behaviour in what were non-violent crimes. Reprehensible as their actions were and disrespectful to survivors and the bereaved of North Kensington, the fraudsters have been handed extraordinarily punitive sentences of between 18 months and 4½ years apparently designed to slake the public’s thirst for justice. These have echoes of the similarly exaggerated sentences handed out following the Tottenham riots in 2011, when within six months nearly a thousand working-class and black kids were given custodial sentences on average four times the length handed out for similar offences the year before, with one man jailed for six-months for stealing a bottle of water. It’s hard to avoid the suspicion that when property developers claim millions of pounds of public money for their private enterprises it’s called a Private Finance Initiative, but when the poor try to do the same it’s called theft and fraud.

In the meantime, not one of the more than sixty professional contractors, consultants, TMO board members, council officers, councillors, civil servants and politicians responsible in varying degrees for the Grenfell Tower fire that killed over seventy people and made hundreds homeless has even been arrested, let alone sentenced. The findings of the Grenfell inquiry, which only began to listen to evidence last week nearly a year after the fire, cannot rule on either civil or criminal liability even within its drastically narrowed terms of reference. And the Metropolitan Police Service has said that its detectives are a long way from handing over evidence to the Crown Prosecution Service, and that the criminal investigation will take years. Again, it’s hard to avoid the suspicion that the wheels of justice turn at very different speeds depending on who’s in their path. There’s a sizeable portion of the British public that wants – if not expects – that criminal investigation to be on charges of misconduct in public office or gross negligence manslaughter (both of which carry a criminal sentence) rather than corporate manslaughter (which only carries a fine). To prepare the way for that not to happen, and for the perpetrators of this crime to walk away free from the crematorium of Grenfell Tower, a radical change in the public’s opinion of those responsible will be required. Enter Andrew O’Hagan . . .

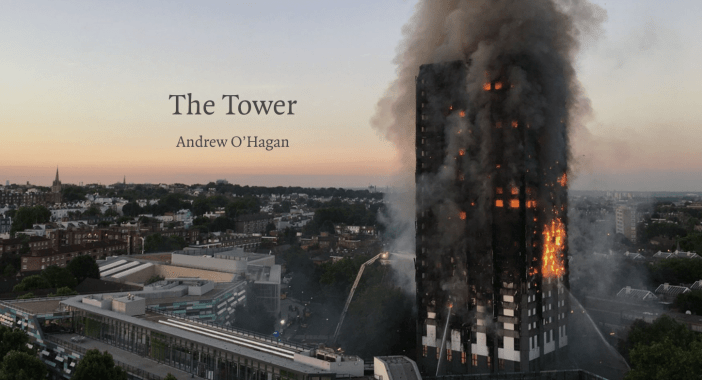

1. The Tower

On Thursday, 22 June, 2017, in response to the Grenfell Tower fire the previous Wednesday, Architects for Social Housing held an open meeting in the Residents Centre of Cotton Gardens estate in Lambeth. Around 80 people turned up and contributed to the discussion – residents, housing campaigners, journalists, lawyers, academics, engineers and architects. The meeting was filmed by WoolfeVision, and has subsequently been viewed over 20,000 times on YouTube. On 21 July, five weeks after the disaster, partly in response to the disinformation being spread about the tower by Labour politicans who were trying to separate the disaster from the estate regeneration programme their councils are primarily responsible for implementing across London, ASH published its report, ‘The Truth about Grenfell Tower’. We sent this report to Joe Delaney from the Grenfell Action Group, and both they and ASH submitted it for consideration as part of the consultation on the terms of reference for the Grenfell Inquiry, to whom the housing and human rights lawyer, Jamie Burton, wrote on our behalf:

‘This report deals with the causes of the fire at Grenfell. It also speaks to recent government policy, both central and local, towards social housing and council estates in particular. Notably, since the fire, many politicians and commentators have stated publically that the fire was in some way indicative of problems common to all tower blocks and council housing estates. Many of these people assume that council and housing association estates are unsafe, inherently flawed in their design, breeding grounds for anti-social behaviour, and generally undesirable places to live. In fact, the evidence clearly demonstrates the opposite to be true. When properly maintained and refurbished, council estates are excellent places for people to live. The problems that do exist in council estates stem not from their inherent design or purpose, but flawed government policy towards them and their residents – policy that the Grenfell Tower fire has brought into focus.

‘It is unclear whether or not the Grenfell Inquiry will consider existing public policy towards council housing and/or tower blocks generally. We consider that it should, as it is critical to a proper understanding of what happened to the residents of Grenfell Tower on 14 June, 2017. However, if the inquiry is not broadened in this way, then at the very least it must avoid adopting any of the unjustified assumptions some people hold about council housing estates and the tower blocks within them.’

Following the publication of the ASH report, which has since been visited over 15,000 times on our blog, we were contacted for interviews by a wide range of journalists and filmmakers, including from BBC Home Affairs, Panorama, Channel 4 News, the Financial Times, RT News, Al Jazeera, Novara Media, and many other people besides. These included two journalists from the London Review of Books, Josh Stupple and Anthony Wilks, to whom I gave a three-hour interview at the end of August that they filmed, they said, as part of the research they were doing for a long-form article on the fire to be published in the new year. As often happens, many of these interviews came to nothing: the sensationalist Panorama documentary went ahead, but without input from us; and when we refused to toe the Labour opposition’s widely accepted line that the Conservative government’s austerity cuts were to blame for the fire the interview requests dried up too. However, I’m a subscriber to the LRB, which I receive through the letter-box every fortnight, and when the new year had come and gone and the article still hadn’t appeared, I wrote to the editor in March, 2018, not in the hope of being published in its letters section, but as a genuine inquiry about their silence on this event:

‘I’ve lost track of how many articles on Brexit the London Review of Books has published since that fateful June day in the summer of 2016, so I was a little surprised to see yet another in the last issue (‘Fall Out: A Year of Political Mayhem’, vol. 40, no. 2, January 2018). But this one, at least, contained the first mention that I have read in your pages of that other incident in the history of the UK that occurred a year later, but about which the LRB has remained steadfastly silent. Following our report into its causes and those responsible, I was interviewed last year about the Grenfell Tower fire by an LRB journalist, who promised me an article would be out in the new year. Brexit, no doubt, has gripped the attention of the LRB’s middle-class readership, who might imagine themselves immune to the causes and consequences of this fire, but there can be few events in the past year on which so many strands of British life converge: the housing crisis, the privatisation of our public land and assets, unaccountability in local and central government, deregulation, foreign investment in London property, the mass loss of social housing, and the estate regeneration programme in which they all meet. For those who think the Golden Age of pre-Brexit UK is something to be missed, Grenfell is a sharp reminder to the contrary, and the failure of the LRB to report on this disaster has become something of an elephant in your offices, which I’ll hope you’ll soon chase away. This may help you.’

To which I attached the link to the ASH report. In reply I received an e-mail from Paul Myerscough, one of the senior editors at the LRB:

‘Thanks for your note. I can’t promise that we will rein in our coverage of Brexit, but I can promise that we shall carry something on Grenfell – by, I imagine, the writer who interviewed you – sometime in the next few months, and that it will be a substantial piece of work.’

As the anniversary of the Grenfell Tower fire approached it became apparent that this would also be when the LRB broke its long silence. And sure enough, this Friday the expected feature-length article arrived, titled ‘The Tower’ and written by the novelist and essayist Andrew O’Hagan, who is listed on the contents page as an editor-at-large. At nearly 60,000 words it’s twice the length of the ASH report, and according to the Channel 4 journalist, Jon Snow, whom it paints in unflattering colours, O’Hagan had a team of researchers at his disposal, presumably including the two I spoke to. Neither my interview nor the ASH report is referenced in O’Hagan’s article, for reasons that will be obvious to anyone who has read the two texts, but he does make numerous references to the accusations levelled against Kensington and Chelsea council, which he dismisses as the ‘ingrained resentment’ of ‘agitators’ – and other, equally pejorative, descriptions of activists that wouldn’t look out of place in the Daily Mail. So I feel that, although O’Hagan has completely ignored all the evidence of the council’s responsibility for the fire that we compiled and discussed over the course of our report, the conclusions he reaches are very much directed at discrediting those we reached, and that we therefore have a case to answer. It isn’t hard to recognise an unflattering portrait of ASH among O’Hagan’s contemptuous description of what he calls the ‘battalion of “local experts” and “community leaders”, quite a few from other areas, keen to speak on behalf of the victims before appearing on the news to denounce the guilty parties.’

More than this, though, I’m genuinely surprised ‘The Tower’ has been published by the London Review of Books, which is itself something of an ivory tower of political correctness and middle-class consciousness, but is always assiduous in dotting the i’s in its well-mannered liberalism. O’Hagan’s article, by contrast, reads like something penned by Boris Johnson for the Telegraph. After writing the ASH report on Grenfell Tower I never wanted to return to it again; but this is such a hatchet job I feel I have to. Given the magnitude of what he’s writing about and the flippancy of his argument, it’s one of the worst pieces of journalism I’ve read – written by a writer who, by his own admission, was looking to move on after the fallout from being Wikileaks founder Julian Assange’s ghost writer, and was doubtless aware of the publicity he’s now getting from being controversial about this most contentious of events. But equally probably, his article is also a strong indication of where the public inquiry will lead in apportioning blame and exonerating guilt. I had thought that one of the reasons the LRB hadn’t written about the fire is that, strictly speaking, it’s a journal for book reviews. So this is my review – which I will be submitting to the LRB – of what I wouldn’t be surprised to learn will turn into Andrew O’Hagan’s best-selling novel The Tower: Rewriting Grenfell.

2. The Novella

There can be few people in London not aware that our Mayor, Sadiq Khan, grew up in a council house. He rarely fails to mention it in his prefaces to the latest bit of housing policy coming out of the Greater London Authority designed to facilitate the demolition and redevelopment of even more council estates. Fewer will have heard of Andrew Adonis, another council estate kid, who has some claim to be the architect of the estate demolition programme, which he was one of the first to propose in 2015 in the IPPR report City Villages: More homes, better communities. Both politicians refer to their backgrounds as some sort of assurance that they have our best wishes in mind, that council estates are what they stand for, where they come from, what they want to make better – that they are, in short, on our side. It wasn’t surprising, therefore, that in his article on the Grenfell Tower fire Andrew O’Hagan repeatedly refers to his own childhood on the Kilwinning council estate in Scotland – not only (as he does) to plug his debut novel, Our Fathers, which is set in these estates, but to assure us that he understands what life on an estate is like, and though he’s now a ‘well-known writer’ – as he expressed it in a text to one interviewee – he’s still got the common touch. Our testimony, is the implication, is safe with him.

But there’s another subtext to this trip down memory lane. Andrew O’Hagan now lives in what the Times newspaper described as ‘an arts and crafts-style house’ in Primrose Hill. From a Glasgow estate to a North London terrace in a single generation – comes the appreciative murmur – not bad! Or as the conservative narrative of social progress inscribed more noisily in our increasingly punitive benefits system spells it out: ‘If I can do this, you can too!’ The arc of this story of self-improvement runs through O’Hagan’s article, which opens with the information that one of the residents who died in the fire, Rania Ibrahim, although she lived on the 23rd floor of Grenfell Tower, ‘liked to imagine that one day she would live in a house’. This is reiterated in the second paragraph, when O’Hagan relates that Mrs. Ibrahim’s friend told him: ‘She did have a preference for small Victorian terraces’. And she’s not alone. Three pages later, he tells us that Sepideh Minaei-Moghaddam, despite living on the first floor, ‘never really wanted to be in a tower. She said she always dreamed of living in a place with a garden.’ Drawn from the same well of aspiration, such dreams are sold to us by estate agents and the think tanks that parrot their sales patter into policy. When Andrew Gimson, the journalist and biographer of Boris Johnson, visited Grenfell Tower after the fire he confidentally wrote in the London Evening Standard: ‘I would not ever want to live in any of those towers. I prefer my little terraced house. So, if they can, do most people.’ O’Hagan clearly thinks the same. On page 13 Mrs. Ibrahim is reintroduced as the woman ‘who dreamed of living in a small Victorian house’ – perhaps one just like Andrew O’Hagan’s. And finally, on page 43 – which is the length of a novella – the story comes to an end with Mrs. Minaei-Moghaddam relocated to ‘a white bungalow surrounded by rosemary bushes out in Twickenham’.

When the previous issue of the London Review of Books finally announced that the next issue would contain ‘Andrew O’Hagan’s investigation into the Grenfell Tower fire and its political aftermath’, I wondered why they’d asked a novelist to write about a disaster which, as I had written to the editors, brought together so many of the political issues surrounding the housing crisis in this country; particularly when the absence of correlation between the official discourse on social housing repeated by government, councils, developers and our national press and the reality of what is being done is anything but common knowledge. Anyone new to this, I thought, will have a hell of time bringing himself up to speed not only on the technical causes of this disaster, but also on the bureaucratic contexts and political decisions that put those causes in place with such terrible consequences. When I started to read O’Hagan’s article, though, I understood why he’d been chosen. As a review journal, the LRB likes to take a narrative approach to its commentary on contemporary political matters, but this is usually confined to an opening paragraph in which the author drops a name or two and a personal anecdote about their interest. But in O’Hagan’s case this is extended to the first two pages of his article. It’s not until we’re into page 3 – the length of some of the shorter articles in the LRB – that the fire even begins.

I know how this works. It’s the compliment that gets paid before the ‘but’ that takes it away. And I can imagine the advice O’Hagan received from fellow writers on how to approach such a politically inflammatory subject: ‘In the name of Allah, make sure you get the residents on your side!’ So he writes about what he’s been told about their lives and what he imagines about their dreams – which, unsurprisingly, turn out to be just like his (a Victorian house with a garden). In doing so, however, O’Hagan adopts the novelist’s convention of calling the residents by their first names – while the councillors he introduces later are always referred to by their surnames. I was reminded of that anecdote of an announcer at Lord’s back in the 1950s – when amateur gentlemen and working-class professionals in the same cricket whites required distinguishing on the field of play – correcting the programme that read ‘Smith, J.’ to ‘John Smith’ – the address by surname being reserved for the gentry and senior staff, while chambermaids, under-butlers, kitchen hands, gardeners and chauffeurs were always addressed by their Christian names. Here the names are mostly Muslim rather than Christian, but the class distinction is just the same: Paget-Brown, Feilding-Mellon, Holgate, Taylor-Smith, Campbell / Rania, Alison, Karen, Miguel, Zainab.

My point in making this observation is that O’Hagan’s article is written not as the ‘investigation’ into the Grenfell Tower fire the LRB described it as, but as a tragic novella, with its powerful and manipulative villains (the government and industry lobbyists), its fateful protagonists (the London Fire Brigade), its troublemaking outsiders (the activists), its blameless victims (the residents), and – and this is the selling point of his novella – its unjustly vilified heroes (the council). Rather like Jane Austen’s equally fictitious Mr. Darcy, these latter are possibly arrogant and undoubtedly socially awkward members of the ruling class rather bamboozled by the mores of our times, but noble in character and deed, as Mr. O’Hagan’s novella (soon to be published by Faber and Faber) will reveal. Indeed, in Chapter VI of his roman numeral-numbered novella, when he writes his own romantic description of the ‘rebellious’ history of North Kensington, O’Hagan doesn’t draw on social histories and economic records of the area but on the novels of Martin Amis, Muriel Spark, Virginia Woolf and Charles Dickens. It’s worth recalling that, in addition to writing novels, O’Hagan teaches creative writing at King’s College London. ‘People tell the stories they need to tell,’ he writes, ‘ones that match their own disbelief, and it doesn’t matter if they’re true.’

O’Hagan’s writes this about the widely-reported anecdote of a resident throwing their child out of a burning window and into the arms of another resident. The fact this turns out not to have happened is emblematic, for O’Hagan, of the stories that sprang up around Grenfell Tower from the moment the fire caught in its cladding. But all those stories are so many plot-strands to the metanarrative, which is what he has decided it is his duty to expose, sifting the false stories from the true, the dead ends from the open doors, the lies – whether deliberate or misguided – from the truth. But like all metanarratives, the story O’Hagan tells is written to give legitimacy to the existing social order, in the same way that the narrative of austerity – which has written our fiscal policies for a decade – draws on the metanarrative that wealth is built on hard work and poverty is a failing of the individual. And like all best-sellers, the purchase O’Hagan’s fiction has on fact is subordinate to the ability of the author to convince his reader to suspend their disbelief at the tale he’s telling, enter into his story, and see the world they thought they knew through his eyes.

That’s not quite true. O’Hagan also refers to Lynsey Hanley’s popular Estates: An Intimate History and Anna Minton’s Big Capital: Who is London For?, both written by journalists, and both very much the introductory texts to the crisis in social housing. But what knowledge he may have taken from these and other texts is dismissed with a politician’s sleight of hand:

‘All of this true and all of it is crucial, and I wonder whether it has a defining part to play in our understanding of the Grenfell Tower fire and its aftermath.’

His readers will never know, as O’Hagan doesn’t apply the criticisms of housing policy in these books to the aftermath of the fire, let alone to its causes, about which he says almost nothing, and what he does say is based on opinions rather than facts. Like all interviewers O’Hagan abjures factual research for personal interviews, perhaps because it makes for better dialogue. Like all journalists he denounces the lies of journalism while telling his own. Like all journalism his only criterion for truth is to balance the testimony of the victims against that of the perpetrators – with the latter, in this case, far outweighing the former. And like all novelists his truth is that of subjective experience, not objective fact. But this, and not an investigation into its causes, is the narrative framework of O’Hagan’s article. Again, it’s worth recalling that, in his article in the London Review of Books about ‘Ghosting’ Julian Assange’s autobiography, O’Hagan writes that he took the job because of his ‘instinct to walk the unstable border between fiction and non-fiction.’

Fiction, as we know, may have little foundation in reality, but that doesn’t stop it bending reality to its requirements and role. Rather than merely marking the anniversary of the fire, it cannot be coincidental that this text has been published to wide coverage in our national press in the same week the Grenfell Inquiry finally began its evidential hearings. No doubt the editors at the LRB recognised the publicity this convergence would bring them; but it is equally doubtless that O’Hagan’s article has been written and published in order to influence public opinion as the public inquiry gets underway. It is unlikely that a factual report – such as, for instance, the one written by ASH – would have achieved these ends. The public has trouble getting through a Twitter post, let alone a 28,000-word article on the technical, bueaucratic and political causes of a man-made disaster. But we continue to devour novels – particularly those based on conspiracy theories, with their dramatic opening scenes (Chapter I: ‘The Fire’), their heroic narrators (Chapter II: ‘The Building’), their selective relationship to reality (Chapter III. ‘The Aftermath’), the twists and turns of their plots (Chapter IV: ‘The Narrative’), their shock surprises (Chapter V: ‘Whose Fault?’), their sifting of truth from lies (Chapter VI: ‘The Rebellion’), and, finally, their comfortable reassurances (Chapter VII: ‘The Facts’). These inevitably conclude that – yes, what we have always believed is still true; that the people who should be are still in charge; that the guilty will be brought to justice by due process; that those who try to challenge this process are well-intentioned, perhaps, but mistaken; that the social order we thought was in peril is back in safe hands; that the people in authority are still watching over us; that the Grenfell Tower fire was a tragedy, certainly, but the country we live in is still ruled by law and order, and we can sleep safe in our beds at night, not wondering whether we’re going to wake up in flames. Who better to tell this story that we know so well but need telling over and over again than a novelist? And what better hook to hang it on than the revelation that the bad guys everyone wanted to see in the dock turn out to be our saviours and the heroes are really the culprits? ‘Mr. O’Hagan, you’ve got yourself a book deal!’

First, though, how to clear the facts for this new story? How can you, when over the past year so many articles on the Grenfell Tower fire have been published, so many facts have been accumulated, so many testimonies of survivors and witnesses recorded? One thing’s for sure, going through them all will lose you readers, not to mention credibility. So let’s create this thing called ‘the narrative’.

What’s ‘the narrative’? O’Hagan first mentions it in Chapter III of his novella (‘The Aftermath’), the second longest of the seven chapters, when he establishes through conversations with council workers that, contrary to the accusations of survivors, the council did a great job of looking after them, finding them beds, visiting them in hospital, distributing the emergency funds, and allocating them housing. ‘But there was a narrative forming,’ he relates a council worker telling him (to these O’Hagan gives pseudonyms – by implication to protect them from the baying mob of his imagination, but he’s still on first-name terms with them). ‘What narrative?’ he asks, his novelist’s antennae pulsing with anticipation. A few more anecdotes of compassionate council workers being pilloried by the press, and the accusation returns with a definite article attached. ‘It doesn’t fit the narrative’, says another. ‘It was just not what they wanted. It wasn’t the narrative.’ Sensing a dramatic turn in an otherwise familiar story, O’Hagan adds inverted commas:

‘But something strange began to happen. A feeling turned into a slogan, and suddenly the ‘narrative’ the social workers talked about was in place.’

But he’s not done yet. Enter a surprising villain, the newly elected MP Emma Dent Coad, who has attained almost saint-like status among the Labour-voting electorate of North Kensington, and who has accused the council she once worked for of ignoring residents’ warnings about the fire. ‘That was the narrative,’ another council workers says. ‘It was the story they wanted: the richest borough neglects people in social housing’. And we haven’t even reached the chapter titled ‘The Narrative’. All O’Hagan needs in order to seal his metaphor to reality is a quotation – which he duly supplies:

‘It was W. B. Yeats’s tower where we each “pace upon the battlements and stare/On the foundations of a house”, sending our imaginations forth to “call/Images and memories/From ruin.”’

It’s an odd quote to slip into an ‘investigation’ into the ‘political aftermath’ of a man-made disaster, but it’s quite at home in a novelist’s musings on that disaster, the kind of quote you’ll find by another Irish writer, James Joyce, as the epigraph to O’Hagan’s non-fiction book The Missing. Facts, however, are not made in fiction, and an investigation into the complex mass of government legislation, GLA policies and council practices that made the Grenfell Tower fire – as an architect and fire-expert O’Hagan doesn’t quote said – ‘a disaster waiting to happen’ should not confuse the two. Perhaps a better quote from Yeat’s The Tower for O’Hagan’s failure to consider this testimony would have been:

If on the lost, admit you turned aside

From a great labyrinth out of pride

Cowardice, some silly over-subtle thought

Or anything called conscience once

Even in a work of fiction such as this, only pride, cowardice, silliness or a lack of conscience could possibly explain O’Hagan’s statement in this chapter that the ‘biggest mistake’ made by the council whose refurbishment of a tower block in their housing stock killed 72 people ‘was perhaps in not looking sufficiently guilty in front of the cameras’. I’d like to know how he got that past the LRB editorial board.

But he isn’t finished yet. In the next chapter (‘The Narrative’), O’Hagan doesn’t shrink from using his own childhood as an example of how fiction becomes accepted as fact, citing an apocryphal story from the Second World War about his grandfather, who it turns out didn’t die trying to save his comrades but rather getting pissed in the hold of a torpedoed cruiser. ‘In every situation pertaining to a public event,’ he concludes from this sobering revelation, ‘people, often with the best intentions, tell lies.’ Well, yes they do, but in O’Hagan’s account it’s only certain kinds of people – specifically, those he addresses by their real first names; the testimonies of the pseudonymous and the surnamed are all, without exception, taken at face value. Whether he’s ever considered that it’s the latter that have the most cause to tell lies I don’t know. Apart from ‘The Tower’ and ‘Ghosting’, I’ve never read O’Hagan’s writing, and so I’m not aware of whether the literary device of an unreliable narrator is one he’s experimented with; but his refusal to countenance the unreliability of the testimony of the councillors and council workers he interviews, or to check their protestations of innocence against the huge weight of documentary evidence, suggests he doesn’t. I think there’s a less sophisticated and more cynical use of the novel form to divide his characters into those whose testimony we can unquestioningly trust and those we should, with his help, interrogate. It’s in this clear division, perhaps, that the ideological role of O’Hagan’s novella is most explicit, and which is most clearly revealed in this chapter in a series of statements which, in their relation to reality and their class loyalty, wouldn’t sound out of place in the mouth of George Carman QC, recommending Jeremy Thorpe MP to Mr. Justice Cantley at the former’s trial in 1979:

‘Paget-Brown isn’t everybody’s cup of tea as a politician. But his dedication to the borough was total.’

‘His gentle manners precede him, in the style of a decently prepped, slightly fogeyish man of the 1950s.’

‘Self-sustaining decency was a commodity in short supply, and I found I liked Paget-Brown.’

‘He has given thirty years of his life as a councillor, and you don’t do that out of a sense of noblesse oblige.’

‘Local authorities work every day in Britain, often demonstrating grace under pressure.’

‘People with decades of experience in public service, employees who really cared for people in social housing, and worked for them every day.’

‘The unluckily posh-seeming leaders of a rich-seeming council, who just happen to have the wrong names at the right time.’

‘People required an answer. So we dried their eyes and blamed the council.’

I’d liked to have heard what the late Peter Cook would have done with such a summary, but perhaps only someone who lives on a council estate can fully appreciate this description of the career politicians, real estate consultants, property developers, landlords and lobbyists for the building industry that sit on the cabinets of our local authorities. Clearly that no longer includes O’Hagan. Interestingly, the main contractors for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment, including Rydon Construction, CEP Architectural Facades, Harley Facades and Studio E Architects, have all refused to make a statement at the public inquiry, presumably because, just like Jeremy Thorpe, they fear saying something that will incriminate themselves. Also interestingly, though, when this last line by O’Hagan is quoted on the front cover of the London Review of Books the editors, perhaps sensing the paternal arrogance in that class division between ‘we’ and the ‘people’, changed it to: ‘So we wiped our eyes and blamed the council.’ Better to be politically correct than sorry. But it’s too late. It doesn’t matter how many times O’Hagan reminds us he grew up on an Ayrshire council estate when he comes out with statements like: ‘The narrative had become part of the common air.’ The credibility of witness testimony, in other words, is determined by O’Hagan not according to its corroboration by anything as vulgar as facts, but by the air they breathe: the common air of the community, whose brief testimonies in their rapid procession in and out of the witness stand he airily dismisses; and the rarefied air of the surnamed, who are given page after page by a fawning O’Hagan to defend their actions and deny the accusations against them.

3. The Smear Campaign

Now for the cross-examination. As anyone will know who has watched the trial of Jeremy Thorpe in the recently aired BBC mini-series A Very English Scandal, or seen the documentaries about the acquittal of O. J. Simpson, or perhaps more pertinently the trial that never happened except on television of former Prime Minister Tony Blair, the best way to defend a guilty man is to undermine the credibility of the prosecution witnesses. This is the task O’Hagan sums up in Chapter VI, which he characteristically titles ‘The Rebellion’, so we know who it is he’s put in the witness box; but it starts much earlier in his defence of Kensington and Chelsea council. Remember that the rhetorical flourishes, the Latin phrases and the Irish poetry are for the judge and the press, but in a case of manslaughter it’s the jury that decides the verdict, and they speak another language altogether.

The residents of Grenfell Tower, as O’Hagan knows, both living and dead, are untouchable; so, as is standard practice – whether he knows it or not – among London councils pushing through estate demolition schemes against the wishes of residents, his invective is directed at what he calls ‘the activists’. This begins, however, with a resident, and one who died in the fire, Steven Power. ‘He hated the way the building had been refurbished’, writes O’Hagan; ‘they say it was a thing with him, complaining about the building.’ But that’s okay, because he owned two bull terriers other residents were scared of, didn’t work and drank both inside his flat and out on the street. It’s a risky move by O’Hagan, describing a victim in this way; but in doing so he’s drawn a template into which all other complainants will be fitted.

Joe Delaney, who lived in the neighbouring Brandon Walk of Lancaster West estate, is introduced in the long Chapter I (‘The Fire’), as is Edward Daffarn, who escaped from the 16th floor of Grenfell Tower; and initially both seem to stand in the role-call of victims – those who lost their homes if not their lives. But both, we soon learn, are also local campaigners and members of the Grenfell Action Group, and Eddie ‘had issued warnings about the safety of the building for years’. By Chapter II (‘The Building’), however, the smear campaign to discredit them has begun:

‘The Grenfell Action Group hate the Tory council.’

‘Over many years, the council had been the enemy and to them every move it makes stinks of corruption.’

Like the council, O’Hagan tries to separate activists from the residents, even when they are drawn from among them, asserting – without any evidence to prove his claim – that:

‘The group had never been very popular on the estate. They had struggled to get anybody to listen to them. But that is the lot of many activist groupings.’

In fact, in July 2013, 94 residents from Grenfell Tower’s 120 households signed a petition to the Kensington and Chelsea Housing and Property Scrutiny Committee, expressing their fears about the fire safety of their homes. In response, Laura Johnson, the TMO’s Director of Housing, dismissed the complaints as the troublemaking of ‘a small number of residents’ – so we know where O’Hagan got that narrative from – and two residents who subsequently died in the fire, Mariem Elgwahry and Nadia Choucair, were threatened with legal action by Vimal Sarna from the council’s Legal Services. Nearly two years later, in March 2015 nearly 100 residents representing over 50 households in Grenfell Tower gathered in the Community Rooms to discuss the problems the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower was causing them; so clearly quite a few residents were listening. O’Hagan, however, isn’t, as it doesn’t fit his narrative.

Instead he continues with his smear campaign against activists. No longer a survivor of a fire that nearly killed him, killed dozens of his neighbours, and turned his every worldly possession to ashes, Edward Daffarn, along with his fellow Grenfell Action Group blogger, Francis O’Connor, are now:

‘Committed local agitators with a deep disgust at what the council and its TMO was failing to do for the poorer people of the borough.’

‘I spoke with the targets of their accusations, and it’s clear there were prejudices.’

Hate, disgust, prejudice: these are the driving force of the herd mentality. And there’s more:

‘In November 2016, the action group’s long history of accusations against the council and the TMO came to a head.’

‘It was merely the latest in a barrage of complaints going back to 2013.’

‘But this Grenfell group was political. They hated everything the council and the TMO did, no matter what.’

‘That was their view and they pursued it obsessively.’

Repetitive, aggressive, obsessive and politically motivated by accusations O’Hagan breezily dismisses with this flourish of his barrister’s wig:

‘In any event, whatever the arguments, the members of the group, who would come to be seen as the wise men and women of the disaster, had a long history of objecting to the council and its representatives.’

For O’Hagan, this repeated reference to how long the Grenfell Action Group had been making its objections are indicative of their passion for doing so, rather than the refusal of the council and TMO to address their complaints. Like Steven Power, is the implication, complaining was ‘a thing’ with them.

And the Grenfell Action Group aren’t the only activists to be smeared by O’Hagan. In Chapter III (‘The Aftermath’), introducing Grenfell United – which was formed after the fire by survivors, the bereaved and the local community – as a ‘secretive, slightly exclusive’ group that filled ‘both ears’ of the Prime Minister with ‘stories of how much they hate the council’, O’Hagan goes out of his way to write that ‘many of the survivors I spoke to had nothing to do with the group.’ And that when he ‘mentioned some activists’ their press contact replied that ‘those people you mention aren’t necessarily involved in what we’re doing.’ Grenfell United, concludes O’Hagan, who implies that he knows all about their kind:

‘Soon became the kind of group that wants to know you’re on its side before it will answer your questions.’

Given his descriptions of them and other activists, perhaps he’d now concede they have a point. Edward Daffarn, meanwhile, was no longer responding to O’Hagan’s questions – not because he was recovering from the trauma of the fire under the glare of the world’s press while struggling to find a home and get justice for his community. No, it was because, O’Hagan contemptuously writes:

‘Daffarn’s days writing to the council were long gone, and now he did half-hour interviews with Jon Snow on Channel Four News unchallenged.’

I know Ed from ASH’s involvement with the neighbouring Silchester estate, whose residents he invited me to come and speak with, and more generally in resisting the estate regeneration programme that threatens to demolish it. Despite the protracted degradation of his living conditions, first by the long construction of the Kensington Aldridge Academy and then by the fatal refurbishment of Grenfell Tower itself, he has always been a happy and friendly person, positive in resisting the injustices against which he struggled. Like many of us who feared for his safety, I was hugely relieved to learn of his almost miraculous escape from the fire, which he relates in harrowing detail in his interview with Jon Snow. But a month after the fire I caught up with him at the demonstration outside Kensington and Chelsea town hall on 19 July when the council announced its new Cabinet. Together with four other survivors of the fire, he had just spoken passionately and incisively in the town hall and looked a different man, still trembling weeks after the disaster, fraught, drawn, hunted, even, by the press. And well he might, after what he’s gone and continues to go through. To impute, as O’Hagan does, that Ed is somehow milking his new-found fame or enjoying his time in the glare of publicity shows only the desire with which O’Hagan himself longs for that publicity, and what he is willing to do or write to get it. And yet it is he who has the temerity to write that:

‘Journalism, hour by hour and day by day, showed by its feasting on half-baked items that it has lost the power to treat reality fairly.’

Indeed it has, and nowhere more so than in this jealous smear against the character of Edward Daffarn and his attempts, in the face of loss O’Hagan can only imagine, to find justice for the dead and the survivors of this terrible fire.

If you’re wondering where this smear campaign conducted against residents who dared to become activists came from, O’Hagan unwittingly gives the answer in his interviews with one of the primary objects of their complaints. Unlike his anonymous subordinates, Nicholas Holgate, the former Town Clerk of Kensington and Chelsea council – about whose forced resignation at the hands of Sajid Javid, then the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, O’Hagan devotes more pages than to any of the series of fatal decisions made by the council that paid him £193,000 per year to be its Chief Executive – is quoted by name:

‘Holgate would later say there was a group of local people who had “an idée fixe” about the council and the management organisation.’

‘Holgate came to suspect that their “deeply felt antagonism” might well be seized upon by the press.’

It has apparently never occurred to O’Hagan that this attempt by Holgate and other council officers to pathologise the opinions of activists is something that requires investigation and corroboration, rather than being quoted verbatim and without question as fact. But to repeat my earlier point, that would be the duty of an investigative journalist researching the causes of the Grenfell Tower fire, not a story spun out of its aftermath by a novelist looking for a new book deal.

By now the pathology of the individual activist has been extended to the mentality of the mob. ‘Community leaders’ are mocked with the addition of inverted commas. The anger of the community is attributed to a ‘limitless disgust’. And celebrities lending their fame to the demands of the residents are ‘stoking misunderstanding in the name of political progress’. It’s hard not to laugh, though, as O’Hagan digs into his deepest drawer of popular tearjerkers to lament:

‘I wondered if the general election, as well as Brexit and austerity, had left the liberal conscience estranged from reality.’

Or perhaps – just maybe – it’s that 23-storey crematorium they see every day, as large as death and just as real. Judging by the reactions of the liberal establishment – from the lamentations of Labourites in the Guardian to the year-long silence of the London Review of Books – I have no doubt the liberal conscience was and still is estranged from the political reality of the Grenfell Tower fire. But those who saw and predicted its eventuality – who lived through and reported its warnings rather than read about them in the paper, and whose anger is not founded on hate, obsession, prejudice, fixed ideas, antagonism, disgust, politics or misunderstanding but on the arrogance, unaccountability and impunity to prosecution of those they know to be responsible for the deaths of 72 people and the violence done to their community by the Grenfell Tower fire – are anything but estranged from reality.

Chapter IV (‘The Narrative’) reads like a copper’s court testimony about the behaviour of activists his squad beat up; or – which is essentially the same thing – a news report about how a small gang of violent troublemakers tried to turn an otherwise orderly demonstration to their own ends (but were bravely contained by our boys in blue). O’Hagan’s in his element here, following the scenes as they unfold before his imaginative eye, and it’s the details in the narrative that hold the subtext for his audience. The day after the fire, he reports, council workers with 25 years of experience were ‘being spat on’. Feilding-Mellen is ‘tremendously upset’ at being presented as a ‘cold-blooded capitalist’. Families made homeless by the fire are accused of wanting ‘a four-bedroom house’ costing ‘two million pound’ rather than the single hotel rooms they’d been crammed into. Paget-Brown is called a ‘murderer’, twice. On the first Friday protesters gather outside the town hall, where the Gold Command installed by the Prime Minister is having its first meeting. Unless he went round an identified each one of them I’m not sure how he established this, but O’Hagan confidently writes that:

‘The crowd wasn’t made up of survivors so much as people who thought like the survivors, or like they thought the survivors ought to think.’

The list of mob invective continues: ‘Murderers!’ ‘Get them out!’ ‘Liars!’ ‘Shame on the media!’ You can tell O’Hagan is enjoying this. This could be his A Tale of Two Cities. ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . .’ A phalanx of police are ‘jostled out of the way’, which must be a first for the Met. More cries of ‘Fuck the system!’ and ‘Get them out! Get them out!’ Next thing we know the police have been ‘overrun’ – another first – and the mob has ‘smashed’ through into the civic suite, ‘smashed’ a glass cabinet containing a bowl presented to mark one of Margaret Thatcher’s anniversaries (have they no respect!), and with a roar ‘broke’ into the office of Paget-Brown (or should I call him Nick?), where they ‘broke’ water jugs and coffee mugs, ‘smashing’ a television set.

I’m not familiar with the exact charges, but so far we’ve got assaulting a council officer, multiple assaults PC, engaging in anti-social behaviour likely to cause offence, breaking and entering, aggravated trespass and criminal damage, all of which O’Hagan lists with a barrister’s deliberation. But it’s not counter charges he’s got his eye on, but rather the character of the protesters, who in their anonymity include anyone protesting at any time, before or after the fire, about the council. This includes, of course, those residents from the Grenfell Action Group, Grenfell United, and any of the other groups that sprang up after the disaster. That includes – let’s name names since O’Hagan has – Joe Delaney, Edward Daffarn, Francis O’Connor and Piers Thompson, the local resident and housing campaigner guilty, in O’Hagan’s account, of shaking hands with Jeremy Corbyn.

But O’Hagan hasn’t finished. A quick trip down memory lane back to his childhood and a time when ‘we didn’t fight a general war with the council’ and ‘the council was on our side’, and he launches into an extended account of the attempts to defraud the funds made available for survivors, by both outsiders and the families of survivors themselves. ‘These allegations are not typical’, O’Hagan writes, ‘so I won’t go into any more of them here,’ which rather begs the question why he raised the issue in the first place. But that doesn’t stop him adding that ‘not one activist I met ever wanted to speak about fraudsters in the community’. If that isn’t an attempt to tar activists and fraudsters with the same brush I don’t know what is. What O’Hagan doesn’t mention, however, are the entirely false accusations of fraud directed against Joe Delaney in a sustained smear campaign by the Daily Mail, The Sun, The Times and The Express, all of which have welcomed O’Hagan’s article with roars of approval and relief. But right on cue, the Thursday after the article was published eight men and one woman were arrested by Scotland Yard in a series of dawn raids on allegations of fraud in connection with the Grenfell fire. This should give us some indication of both the weight O’Hagan’s account carries and the role it is playing.

There’s a passing chance, in Chapter V (‘Whose Fault?), to describe the protest at the town hall as a ‘riot’, a quick reference to the ‘ingrained hatred’ in the local community in Chapter VI (‘The Rebellion’), and a scene of working–class racism as cynical in its implications as the reference to the fraudsters, and we’ve finally reached Chapter VII (‘The Facts’), the last in O’Hagan’s novella.

By the time Sir Martin Moore-Brick had been made chairman of the public inquiry ‘council workers’, O’Hagan tells us, ‘had long since stopped wearing their ID badges because they were being spat at.’ The lawyers have moved in, and are advising survivors living in hotel rooms to reject the council offers of temporary housing in the expectation, O’Hagan writes, ‘they would be permitted to buy new, expensive flats at the same Right to Buy prices as obtained when they lived in Grenfell Tower.’ Once a scrounger, M’Lud, always a scrounger. But there’s more.

Having found Paget-Brown and Feilding-Mellen to be capital fellows, O’Hagan turns to the defence of the new council leader, Elizabeth Campbell, a photograph of whom at this point in the online version of ‘The Tower’ shows her looking frail but concerned, a picture of decency in the face of the intolerable boorishness of her constituents. You can imagine O’Hagan, one thumb tucked behind his gown, addressing the gallery with an air of dawning revelation:

‘It was odd suddenly to be in the company of so many people who hated councils. I began to wonder if it really was the council that people were angry with, or was it authority in general or unfairness in principle. Were they visiting their frustration about the global order on a well-spoken mother of four?’

A final summing up, a final character assassination of the ringleaders, and the whole case against the council will collapse. Edward Daffarn is called back into the dock, only now he’s a ‘key weapon’ in the campaign to save Worthington College from demolition, someone of whom councillors and even government ministers are now ‘terrified’. There’s that word. Terror. But now, apparently, ‘even the groups themselves began to suspect each other of using the fire as an excuse to do politics.’ This is O’Hagan’s cue for further platitudes straight out of the estate demolition handbook:

‘In any situation where local activism has a part to play, in any workplace, on any housing estate, it is the more vocal and radical figures who attract the media. There were always a few residents who were unhappy and they were the ones who wrote blogs and emails to the council and who went on the news after the fire.’

Such accusations are standard fare for councils intent on dividing residents from the support of activists while at the same time denouncing that support as noisily unrepresentative of what they condescendingly call ‘the silent majority’. As emblematic of his perpetually unhappy kind, Joe Delaney, writes O’Hagan, ‘appears to enjoy being a thorn in the side of councillors and officers.’ And though a logical speaker, ‘he only had time for the convenient end of any argument.’ O’Hagan’s judgement is final and damning. ‘This makes him a politician.’

The defence rests, M’Lud.

4. The Factoids

To turn his description of the deceased Grenfell Tower resident Steven Power against him, Andrew O’Hagan has a thing about facts: he can’t stop mentioning their absence but he never gives any himself. In fact, thanks to word search, I can relate that he mentions facts 39 times in his article. Five of those are in his opening lines:

‘From her flat on the 23rd floor, Rania texted one of her best friends from back home and they talked about facts. Who you love is a fact and the meals you cook are facts. When the sun shines it is a fact of God and England is a fact of life.’

The metaphor’s a bit clunky, but you get his point. Facts are important in different ways to different people. For believers God is a fact. For patriots England is a fact. For lovers it’s love. So what kinds of facts are important to O’Hagan?

Well, the first, in Chapter I (‘The Fire’), is that:

‘These blocks are supposed to be built in such a way that a fire can’t spread in them, so the firefighters, most of them (there were about two hundred by two o’clock in the morning), were putting people in “safe” flats that weren’t in fact safe.’

It’s customary to refer to council housing as a ‘block’ when you’re intent on maligning some aspect of it, but Grenfell Tower was constructed with fire safety measures built into its architecture; it was the cladding that wasn’t safe, circumventing and rendering all those measures redundant.

The second, in Chapter II (‘The Building’), relating to the refurbishment of the tower is that:

‘The many bodies doing the work would pass along false options, for example, between this metal and that metal; one of them may be marginally more fire-resistant than the other, but both ‘of course’ meet industry regulations. In fact neither truly meets the standards by any true measure, and in any event the regulations aren’t properly enforced.’

Which is closely followed by O’Hagan’s third fact:

‘The fact that no inspector will deeply investigate the flammability and contradict the choices made is chiefly the result of privatisation.’

That’s largely true, but avoids the fact that it was the council that privatised the management of its housing stock, which it still, nevertheless, owns. The fourth fact is rather less deniable, but that’s because it’s a quote from an e-mail sent by the Grenfell Action Group to Ben Dewis, fire safety team leader at the London Fire Brigade:

‘A number of residents of Grenfell Tower are very concerned at the fact that the new improvement works to Grenfell Tower have turned our building into a fire trap.’

But that’s enough for O’Hagan. There are facts and facts. Theirs and his. We still haven’t heard what his are based on, but theirs! Well, it’s that liberal conscience again, factually estranged (twice) from reality:

‘Reality wasn’t good enough, the tragedy wasn’t bad enough, it had to be augmented, it had to be blown up, facts couldn’t be gleaned quickly enough, and stories went without investigation, research, tact or even checking. In a world of perpetual commentary in which everyone and anyone is allowed their own facts, accusation stands as evidence.’

Which is a bit rich coming from him. Chapter III (‘The Aftermath’), and we’re back on ‘the narrative’:

‘“It doesn’t fit the narrative”, another one said, “but in actual fact there were too many helpers. And there were too many donations. And there were too many crazies. But you won’t hear that on Newsnight.”’

Damn those crazies with their alternative facts and their fake news. Though we still haven’t heard what makes O’Hagan’s facts different (apart from the fact he lives in an arts and crafts-style house in Primrose Hill). Then he’s back on that fake story about a child being thrown out of a burning window:

‘Police have no record of any such incident and “witnesses” later asked themselves whether they had, in fact, seen anything of the sort. The paper had photographs to accompany the story, purporting to be of “Pat” and the “dropped tot”; in fact the man was Oluwaseun Talabi, the man from the 14th floor who had tried to save his daughter from the burning tower by climbing down bedsheets with her clinging to his back.’

Which itself sounds incredible enough to me, so it’s not clear why O’Hagan belabours the point except to undermine the testimony of witnesses. But why believe one story and not another when neither bear on the credibility of testimony to what is the focus of his defence – the behaviour of the council in the aftermath of the fire?

Now we’re on Chapter IV (‘The Narrative’), and more trite speculation from O’Hagan on the psychological origins of fake facts:

‘In fact, 72 people is a huge number of people to die as a result of negligence. Saying that number made many people angry, but, if you stuck around and asked more questions, you began to see that it was the anger that was limitless, not the number of victims.’

Having accepted which opinion as fact, it’s now that the screw of O’Hagan’s plot turns:

‘People want to disimprison the facts, as they see them, and division came very quickly to Grenfell over what was real and what wasn’t. Who was really helping the victims, and who wasn’t? Who actually was a victim, and who wasn’t?’

But if the council workers (this insinuates) are the ones who are, in fact, helping the victims, then everything said by the other victims – who actually aren’t victims and aren’t helping – must be a lie, and the real victims are . . . the council. It’s a subtle argument by m’learned friend, which condemns one group of people as liars as it elevates the other group to truth-tellers; but it lacks one thing to make it convincing. Facts.

Next we’re on to the source of Theresa May’s unhappiness with the council in the unhappiness of ‘the community’ – those quotation marks placing even the fact of its existence in question:

‘When I asked Paget-Brown about this conversation he didn’t dispute the facts, but he tried to be kind about the prime minister, saying that it was very soon after a close general election and she had cause to be nervous.’

So some facts, it seems, are politically expedient when not saying them is an act of kindness. Unlike others. When the Grime artist Stormzy, during his performance at the Brit Awards, demands: ‘Yo, Theresa May, where’s the money for Grenfell?’, O’Hagan wipes the sides of his mouth and responds:

‘The words got a big cheer and an even bigger cheer all over the internet, but there wasn’t, in fact, a single pertinent syllable in them. It was just another rich pop star taking advantage of people’s pain to sound relevant.’

Which apparently is nothing like a ‘well-known writer’ taking advantage of people’s pain to sound controversial. Then it’s Chapter V (‘Whose Fault?’), which you’d hope would draw forth some facts. And it does, starting with this one about the responsibility of Rock Feilding-Mellen, Kensington and Chelsea council’s former Deputy Leader and Cabinet Member for Housing, Property and Regeneration, for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower between 2014 and 2016 and the selection of the cheaper, less fire-retardant cladding that went up like a tinder box and left 72 people in ashes. You’d think the answer was in his job title, but no:

‘In fact, Feilding-Mellen, far from wanting to save money, states in his email of 18 July that he would support the more expensive option.’

This is clearly important to O’Hagan, as he repeats it again at the end of the chapter:

‘They were not on a mission to cut costs: in fact they raised the amount spent on the refurbishment by £4 million.’

But it’s not these facts that are O’Hagan’s real concern. The real facts, for him, like the fact of God for believers, is determined by where your allegiances lie, and his are clearly with the behaviour of the upper classes he so admires:

‘More even than Aberfan or Hillsborough, the public discussion of Grenfell was political from start to finish, and the fact that Paget-Brown refused to get involved in political mud-slinging, or tried to rise above it, was about to bring his career to an end.’

Well played that man. At which point, like many a commissioned officer before him (including, most famously, our Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson), Paget-Brown issues his stirring call to the troops. ‘Pickanninies on the town-hall steps! Form square! Fix bayonets! Prepare to repel fake news!’

‘“This was the most serious thing that had ever happened in the borough,” he said. “I wanted to get all the councillors in and hear what they had to say. And I wanted to give them some basic facts.”’

And like many a loyal unionist before him, C/Sgt-Major O’Hagan comes running to defend the Queen’s colours. ‘The trouble is, Sir, the bloody natives have done a deal with the government behind our backs and got their hands on some ordnance. I fear we may be facing another Isandlwana. Not only that, but the senior officers and subalterns are abandoning their posts!’ O’Hagan brushes a manly tear from his cheek, straightens his neck stock, pulls out an 1879 edition of The Illustrated London News and pens a scene worthy of the Decline and Fall of the British Empire:

‘Feilding-Mellen stood up and scratched his head, before walking out with his colleagues. It was extraordinary that, after receiving word of an injunction, the council’s law officers had not gone immediately to the chair to say the meeting couldn’t go ahead. Now, on top of everything else, the leaders appeared to be censoring the facts. It was a shambles.’

This pathos, remember, is not for the survivors of a fire that reached 2,000 degrees centigrade; not for the 223 residents who lost every material possession they owned to the flames; not for the 82 households who are still living in emergency accommodation a year later; and not for the 72 dead who went to bed and woke up in ashes. It’s for the council careers of Nicholas Paget-Brown, who is Managing Director at Pelham Research, which analyses government policy and offers management briefings on public policy for businesses and local authorities, and Rock Feilding-Mellen, who is Director of a range of companies, including property developers Socially Conscious Capital Ltd, SCC Longniddry Ltd, Vilnius Investment Management Ltd, and UAB May Fair Investments, which is registered in Lithuania. Oh, the humanity.

In Chapter VI (‘The Rebellion’), there’s just enough time for some more pretty dubious facts to excuse the council from privatising and demolishing its housing stock:

‘In fact, London has never not had a housing crisis.’

‘Amid the accusations of social cleansing and profiteering, official housing figures suggest that Kensington and Chelsea Council has a pretty good record of protecting social housing. In fact the social housing stock has actually gone up over the past twenty years by about two hundred dwellings.’

So that’s 10 new homes per year. Another 320 years and the 3,324 households on the council’s housing waiting list will be housed! Finally we’ve reached Chapter VII (‘The Facts’). Yet, despite its title, facts are conspicuous by their absence. Indeed, it is in the assertion of their absence rather than the corroboration of their presence that facts play their role in O’Hagan’s novella, in which this chapter opens with an evocative description of his increasingly heroic quest as a latter-day Stephen Dedalus:

‘I’d walk around the tower, sometimes at the crack of dawn, trying to work it out, listening to new voices or veteran complainants or going into bunkers with the council, taking trains to sources and specialists, and staying up late with maps and plans. Looking for facts: asking what they meant and what the opposite meant and going back to the start. It seemed pointless sometimes, as if I was rehearsing an old way of doing things, hunting for facts, believing in them, when the news was all fiction and the story was sorted.’

‘Signatures of all things I am here to read.’ Indeed. But perhaps, if he was less intent on writing another Ulysses and more committed to researching the Grenfell Tower fire O’Hagan might have written a less flowery but more factual account of its causes. But that, as we have seen, is not what he is interested in. Quite the contrary:

‘I met with countless activists, and recorded what they said, checking it as I did with every witness. They had loud voices and good causes but what they didn’t have was facts. I have quoted from their blogs and referred to their accusations, but I had trouble substantiating them. At times they seemed to be throwing accusations into the air like confetti at a whore’s wedding, but when I tried to follow them up, I couldn’t prove them right.’

It’s a strange metaphor for his own failures as a researcher – which I’ll leave it to O’Hagan to defend as a writer. But let’s give the young Dedalus a hand and lead him, Bloom-like, not to the whore-house of his imagination but to the evidence of his assertions.

5. The Evidence

So let’s start with the one I quoted at the end of the previous section about Joe Delaney, about whom O’Hagan writes:

‘Delaney claims, contra what I later found, that the council didn’t help residents into hotels after the fire and didn’t prove easy with its financial payments and other support. He provided no evidence.’

Now, this is a big issue for O’Hagan. Indeed, the bulk of his article is devoted to a defence of the council’s actions in the aftermath of the fire (he says almost nothing of its actions before, but I’ll come to that later). It is primarily the accusations by survivors such as Edward Daffarn, the press that published them and the government that accepted them as truth that constitutes, in O’Hagan’s reading, ‘the narrative’. And the bulk of his research appears to have been interviews with council workers whose testimony contradicts these accusations. So there’s a lot riding on his claim that Delaney ‘provided no evidence’.

In response to this claim, which appears on the second-last page of O’Hagan’s article with all the resonance that gives it in the minds of the jury, Delaney wrote on his Twitter account last Sunday:

‘I gave O’Hagan recordings of some of the many calls I made on behalf of neighbours to “helpful” RBKC staff in the days & weeks after the disaster to obtain accommodation – they were utterly useless.’

‘If anyone at LRB is paying attention, I will happily write something in response – with evidence – to show how inadequate the response from RBKC was (and continues to be) to all those affected by the Grenfell Tower disaster.’

Which sounds very much like a challenge, and it’ll be interesting to see if the London Review of Books accepts it. But more importantly, for our purposes, the two claims are incompatible, and either Joe Delaney or Andrew O’Hagan is lying. I’ve only met Joe once, so I don’t know what he’s like, but apart from the ordeal he’s gone and is going through, not only from the trauma of the fire but from the aftermath of living in a single hotel room over the past year, he has also, as I’ve mentioned, become a target for the right-wing press, who have accused him of living in the lap of luxury at the tax payer’s expense. He’s also been involved in giving witness testimony to the Metropolitan Police for the public inquiry. He is, therefore, under considerable public scrutiny, and I’d be very surprised if he told a lie in public about the evidence O’Hagan claims he didn’t provide.

O’Hagan, by contrast, appears to be rather less careful with his facts. His article was barely out when the Channel 4 journalist Jon Snow responded that far from doing ‘a series of un-challenging interviews with Eddy Daffarn’, the only interview Ed gave was on 21 May, 2018, less than two weeks before O’Hagan’s article was published. In addition, Melanie Coles, a local resident and teacher – some of whose pupils died in the fire – has accused O’Hagan of misquoting her and other inaccuracies, she writes, ‘that could be seen as damaging to the credibility of our community at a time it is essential our voices are heard.’ And Luke Barratt, a journalist for Inside Housing, has listed a number of factual errors in O’Hagan’s article relating to the fire risk assessment of the refurbished tower, and specifically the absence of proof for O’Hagan’s claim that a desktop study was made of the cladding, which the inquiry has already revealed wasn’t done. He also challenges the factual inaccuracy of O’Hagan’s claim that a fire risk assessment wasn’t made after the cladding was applied, for which Barratt, along with Pete Apps and Sophie Barnes, have produced evidence that the Fire Risk Assessor, Carl Stokes, assessed the building in 2016, after the cladding had been applied to Grenfell Tower, but for some reason he will hopefully have to explain at the inquiry didn’t include the cladding in his assessment.

So just on these initial responses to the factual accuracy of O’Hagan’s claims, his repeated dismissal of the claims of residents and activists as being without evidence is looking, at best, like the pot calling the kettle black, at worst as a deliberate attempt to deny that evidence to further his own attempt, in this article, to undermine the credibility of their testimony. Now, not having lived in either Grenfell Tower or North Kensington, I have no personal knowledge of the credibility of those claims, and I won’t try to pre-empt what I hope the inquiry will reveal about their truth. But I do want to look at what I do know about the factual basis of O’Hagan’s claims. This is difficult, however, because O’Hagan is pretty guarded about what he concedes as evidence:

‘Many people believe, and there is some evidence for it, that the positioning of the new academy school knocked out too much space for fire vehicles to park.’

Indeed there is, and in January 2013 the Grenfell Action Group wrote a warning about precisely this to the Tenant Management Organisation. Mostly, though, O’Hagan only concedes the existence of evidence when it serves his argument that responsibility for the deaths in the Grenfell Tower fire lies with the deregulation of fire safety by the government:

‘The [2009 Lakanal House] fire was evidence that regulations were being ignored by a construction industry keen to maximise profit.’

‘There is strong evidence that a concatenation of failures at the level of industry regulation and building controls, more than anything else, caused the inferno that killed 72 people.’

He’ll get little argument from me there. But in contrast, when it documents the seven years and hundreds of ignored complaints issued by the Grenfell Action Group against the TMO and council, the evidence is diminished into irrelevance, denounced as politically biased or dismissed as populist sentiment with such phrases as:

‘There is evidence that the organisation, although it included residents, wasn’t too keen on those who vocalised objections to it.’

‘The evidence he showed me demonstrated several instances of rudeness and slipshod behaviour and minor incompetence on the part of the council, but no homicidal intent.’

‘The fire gave the opportunity to say boldly – with new, terrible evidence – what they’d always been trying to say about the Tories.’

‘With no evidence beyond a few blog posts and the converging astringencies of ‘public opinion’

‘In a world of perpetual commentary in which everyone and anyone is allowed their own facts, accusation stands as evidence.’

‘“Evidence” for true believers gathers in the space between assertions.’

All of which sets up another opportunity for O’Hagan to characterise deceivers of the council’s original innocence with a reptilian and suggestively Biblical metaphor for the dishonesty and greed of their accusers:

‘Many people liked being asked to provide opinions, but they didn’t want to be asked to provide evidence, and they gently slid away.’

‘I have evidence of several lawyers advising their clients to reject flats in the expectation that down the road they would be permitted to buy new, expensive flats.’

In contrast to which, once again, O’Hagan’s commitment to the council workers is very different:

‘They were relieved to speak, at last, and I set out to corroborate everything they said with documentary evidence.’

As is his prima facie acceptance of the truth of what they say about themselves, such as this from Nicholas Holgate:

‘As a civil servant for 24 years and a local government officer for eight and a half years I was trained to be impartial, objective and evidence-driven.’

Which – as anyone who has had to deal with these unelected council officers being paid quarter of a million pound salaries and more from our council tax will know – contradicts the evidence O’Hagan never produces to corroborate or question these self-regarding claims. These are matched by his own unshakeable faith in the innocence of the councillor and cabinet member whose job it was to oversee the fatal refurbishment:

‘Feilding-Mellen had overseen the decision, and after the fire it was taken as further evidence of the council’s arrogant approach.’

‘Feilding-Mellen was being roundly hated in the press before any of the evidence had been presented, and vilified by the activists.’

‘There is no evidence that Feilding-Mellen ever aimed permanently to displace the residents of the tower.’

‘It helps people to think of it that way, even if there is no evidence for anything of the sort.’

In fact, there is ample evidence to the contrary, much of it collected in the ASH report, but again, O’Hagan never addresses it. Even the accusation that a council which chose an estimate by Rydon that undercut its competitor by £2.6 million for the refurbishment of Grenfell Tower at the time had £283 million in capital reserves and £21 million in its Housing Revenue Account is turned into evidence of its efficiency:

‘A council’s reserves are usually taken to be evidence of good management.’

And it’s not as if O’Hagan didn’t try (he says) to find the evidence to corroborate the accusations of activists against the council. Indeed, with a nod to his working-class roots he tells us that initially, ‘like everyone else’, he thought: ‘Let’s get the bastards who did this’. But as his middle-class individuality pushed through the green fuse he begins to question the narrative:

‘I asked the council’s severest critics for evidence to back their claims [but they] found it difficult to supply them.’

Cue another round of adjectives describing these claims for the benefit of the jury: ‘colourful’, ‘provocative’, ‘damning’, ‘suggestive’, ‘robust speculation without evidence’. Unfortunately, since O’Hagan doesn’t identify or discuss any of this evidence, let alone disprove its veracity with his own research, we have to take him at his word – which, as we have seen, is that of a novelist. And yet it is he who writes that the accusations of these critics:

‘Depended on one’s mind already being made up before one considered what [they] supplied as “evidence”.’

One of the most extraordinary things about O’Hagan’s extraordinary article is that in its 60,000 words – more than twice the length of the ASH report – almost no facts or evidence are presented: only emotive, unsubstantiated, occasionally slanderous and overwhelmingly class-based attributions of truth or falsehood based on who is laying claim to either. On the one side are the residents, the activist groups, the community, the press, the government, the people, all of whom speak falsehoods; on the other are the council and its workers, all of whom speak the truth. Where the Tenant Management Organisation or the private contractors and consultants they hired stand in this simplistic division isn’t clear because, even more extraordinarily, O’Hagan barely mentions them in his novella. Or rather, they are excised from his narrative for the obvious reason that, were they allowed to take the witness stand, O’Hagan’s account of the innocence of unfairly accused councillors and workers would be revealed to be the fiction that it is. In this alone, perhaps, does O’Hagan’s novella bare comparison with reality, since holding their silence is precisely what the private contractors and consultants responsible for managing, designing, constructing, applying and signing off the deadly cladding to Grenfell Tower have done since the day of the fire. The fact they universally claimed to be doing so either as a ‘mark of respect to the people of Grenfell Tower’ or because they didn’t want to ‘prejudice the public inquiry’ has been shown to be the self-serving lie it is by their refusal, this week, to speak at that inquiry.

So what is the evidence in the case of Mr. O’Hagan?

6. Who’s Guilty?

Without waiting for the deliberations of the jury, O’Hagan reaches his conclusion at the end of Chapter IV (‘The Narrative’), which he states unequivocally:

‘The council leaders did not cause that fire.’

So who did? O’Hagan makes his accusation early on in Chapter II (‘The Building’), which he states with equal certainty:

‘We don’t like to say these things, but events on 14 June show that, regardless of our affection for them, the professional fire services’ response to the fire at Grenfell Tower was anything but strong. The biggest weakness, all my sources agreed, was the slowness in telling residents to evacuate. Quite simply it caused nearly all of the 72 deaths.’

It’s typical of O’Hagan’s scattergun approach to deflecting blame away from the council that two paragraphs later he’s laying it elsewhere:

‘Other people would be found to blame, but manufacturers, and those who help them get away with unacceptable standards of fire safety, are the culprits in this case.’

And on the following page it’s no longer the fire services’ response to the fire but the writers of building regulations and building control inspectors that are responsible:

‘There is strong evidence that a concatenation of failures at the level of industry regulation and building controls, more than anything else, caused the inferno that killed 72 people.’

However, this is old news, told numerous times, in varying degrees of accuracy, over the past year. What O’Hagan is after is something new, something controversial, something that will get him noticed, something no one has said before. And it’s on his accusation against the firefighters – so beloved of the community O’Hagan places in inverted commas – on which his plot turns. O’Hagan devotes the whole of Chapter II to making this accusation, for which his novelistic description of the fire in Chapter I (‘The Fire’) serves as evidence.