Uranium, plutonium, polonium, beryllium, all contain the Latin suffix ‘ium’ from Greek ‘ion’, which is used to form English nouns from Greek or Latin words, including biological structure (mycelium), regions of the body (pericardium) and metallic elements (sodium). Yet, for some reason, 335 million Americans say ‘aluminum’ instead of ‘aluminium’. Why?

1. Americanspeak

American, as it is spoken today, is a relatively new dialect of English. Contemporary American is significantly different from the post-war American spoken as late as the 1970s, and almost unrecogniseable from that spoken before the Second World War. Of course, the sibilant twang of the Californian is as different from the growled consonants of the Mid-Westerner as it is from the nasal vowels of the New Yorker or the Texan drawl. What I am referring to is not accent but grammar and syntax, with which contemporary American has colonised the people of the United States through its media and entertainment industries. A product of the neoliberalisation of US culture since the 1980s, contemporary American works to sever its speakers from the thousands of years of European culture from which both they and the language emerged.

I worked in US academia for two years in the early 2000s, and I was struck by how even the most educated Americans — professors and students alike — struggled to articulate themselves. In their mouths, American was a foreign object rather than their native tongue. That’s because American, as spoken today, is not an organically developed language — neither a national nor a regional dialect — but rather an ideological tool of US hegemony.

Incorrect words universally used in American include ‘America’ (the continent) for the United States of America; ‘buffalo’ (an animal of the ox family in India and Africa) for bison (an animal of the ox family in Europe and America); ‘ass’ (an older term for a donkey) for arse (a slang word for the buttocks); ‘phenomena’ (the plural) for phenomenon (the singular); ‘alternate’ (describing the movement between two things) for alternative (designating another choice of something); ‘people’ (a collective noun) for persons (the plural of person); ‘momentarily’ (a brief period of time) for soon (an imminent occurrence); ‘superlative’ (the end term of a grammatical progression: e.g. good, better, best, bested), for superb or best; ‘problematic’ (a noun derived from the French problématique referring to a theoretical context) for contentious or difficult; ‘regular’ (a quality) for medium (a size); ‘learn’ (a passive verb) for teach (an active verb); ‘good’ (an adjective) for well (an adverb); as well as such mangled neologisms and mispronunciations as ‘irregardless’ for regardless, ‘expiration’ for expiry, ‘toleration’ for tolerance, ‘homogenous’ for homogeneous, ‘foilage’ for foliage, ‘nucular’ for nuclear, ‘Isreal’ for Israel, and, of course, ‘mispronounciation’. No doubt there are dozens — perhaps hundreds — more.

But Americanisms go far beyond the misuse, mispronunciation or misspelling of English words. Ostensibly obeying the same rules of grammar, American sentence structure in spoken and written practice is completely different to English. Importantly, this is not a signifier of class, intelligence or education, with presidents, professors and street kids all speaking much the same jargon. Listen to any interview with Bill Gates, who was born into the US upper-middle-class and educated at a private school and Harvard University, and you can hear (and see, as he flails his hands through the air) the struggle that even the wealthiest and best-educated Americans have with their language.

Typical American syntactical structures include ‘Can I get’ (for a request to have something), ‘I need you to’ (for a request to do something), ‘I’d gotten’ (for becoming, owning or developing something) ‘grow your’ (for expand, increase or extend something), ‘my bad’ (for admitting a mistake), ‘takeaways’ (for conclusions), ‘do the math’ for calculate, ‘I could care less’ (to mean one couldn’t care less); while grammatical mistakes entrenched in American include mistaking verbs for nouns (‘batter’ for batsman), the addition of the suffixes ‘ize’ to turn nouns into verbs (‘burglarize’) and ‘wise’ to mean with respect to (‘comfortwise’), and, since the 1990s, the word ‘like’ inserted several times into every sentence, sometimes in place of a preposition or conjunction, but more often as a kind of verbal tic that reduces American speech to absurdity. ‘Like, you know, I just, like, wanna, like, be myself. Like, freedom is, like, my right as, like, an American. Do you, like, know what I mean?’

I do — just; but my question is why such rudimentary sentiments require such a tortured syntax, as though the speaker were grappling with the limits of language in a proposition of Heideggerian complexity, rather than repeating the trite vocabulary of US advertising. The struggle sounds Herculean in the effort required, but it’s the speech of an infant struggling to articulate its basic desires, a dribbling mouth longing for its mother’s breast, and with the same conviction that nothing in the world can possibly be as important as expressing them.

As a result of this lack of grammatical knowledge — which is greater even than native English speakers, few of whom know an adjective from an adverb, a definite article from a past participle — few Americans write in sentences or paragraphs. The one-sentence paragraph without a verb is a product of American, and is now used in everything from academic papers and newspaper editorials to ministerial speeches. The grammar of American is designed to hinder articulation, clarification, precision, description, innovation, discussion. Its contrary purpose is the unthinking repetition of cultural clichés (‘America is the leader of the free world’), the entrenchment of fabricated social norms (‘transwomen are women’), and the naturalisation of contingent political truisms (‘Isreal has a right to defend itself’), that both prohibit and relieve the speaker from the burden of thinking.

As an example of which, I recently came across an article by a Hong Kong academic who has been educated in universities in North America — both the USA and Canada — as well as in Hong Kong. The title of her article was: ‘Regional impact of rail network accessibility on residential property price: Modelling spatial heterogeneous capitalisation effects in Hong Kong’. The lack of clarity in this title falls on whether the adjective ‘regional’, which qualifies a noun, describes the ‘rail network’ or the ‘residential property’. It cannot describe, as its place in the sentence implies, the ‘impact’ the accessibility of rail networks have on the price of those properties. Even worse, ‘spatial heterogeneous capitalisation’ is a meaningless concatenation of words (presumably it is the space that is heterogeneous rather than its capitalisation, which is what the syntax suggests), to which the addition of the word ‘effects’ doesn’t impose a grammatical structure.

Because of this, it’s unclear from the words alone to what, exactly, this title refers; but in English it might read: ‘The impact of the accessibility of regional rail networks on the price of residential properties: Modelling the effects of the capitalisation of heterogeneous spaces in Hong Kong’. Whether or not this is what the author of the article meant, the English title clearly indicates what the article is about, which is not the case with the American title. The fact this article was written not by a native English speaker but by someone who, presumably, learned her English in the US or from an American teacher, or at least learned her academic English in the US, shows how effective a tool contemporary American is in inculcating its speakers, writers and readers into its grammatical habits of thought.

Thought is made in language, and without the language in which to think, Americans and those who learn their language across the world — rather than grammatically-correct English — cannot think, cannot question, cannot oppose its indoctrinated orthodoxies with new thoughts. All they can do is speak American.

2. American Imperialism

Someone once sang that there’s no sadder sight than that of an Englishman in a baseball cap; but far sadder, for those of us who still speak English, is the sound of an Englishman speaking American. If you’re looking for a reason why the English today — and particularly our youth — are so compliant and ignorant — and so ignorant in our compliance, so sure that our opinions are our own and not those we have been indoctrinated into repeating — one of its causes is the language we’ve been taught to speak, not only in English schools, but above all by the US cultural and entertainment industries that have colonised our now redundant English equivalents.

American is a tool in the formation of the West during the Cold War out of Western Europe, Australasia and the USA to the exclusion of Eastern Europe, including, especially, the Soviet Union and now Russia. And just as US consumerism has colonised Europe not only with its commodities but also with its values, so too the people of Europe have learned to speak its jargon, the purpose of which is to prevent them from thinking critically. And the first thing we have been prohibited from thinking about is our own colonisation.

The exception is France, which recognised post-war US consumer culture and the American language for what they are, and tried — unsuccessfully — to protect their own culture and language from its influence. Significantly, it has been through immigrants from France’s former colonies in North Africa that US ideology, in the form of Hip-Hop music and culture, has entered France.

If we were to stop and think in English for a moment, we might recognise the artificiality of the West as a geopolitical construct: that, for instance, 75 per cent of Russians live in Europe; that Russians constitute 15 per cent of the population of Europe; and that European Russia — that is to say, west of the Ural Mountains — covers 40 per cent of Europe’s landmass. Indeed, European Russia is the largest and, with 110 million people, the most populous country in Europe. Moreover, the history of Europe is unthinkable without Russia, culturally, religiously and militarily. Russia fought on the UK’s side in two World Wars in the Twentieth Century, and without it Europe would already be fascist. Yet this is the nation that the USA, a country of immigrants on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, tells us is the East and a threat to Europe.

If we were to think in English, rather than speak in American, we would be able to draw conclusions from the fact that, in its 240-year history, the USA has not been at war for only 16 of them; that the USA has waged 80 per cent of the conflicts across the globe since World War Two; and that since 1945 the USA has tried to overthrow more than 50 foreign governments, interfered with elections in 30 foreign countries, and made attempts to assassinate around 50 foreign leaders.

The conclusions we could draw in English from these facts might include that Europe, today, is occupied by a foreign army, but it isn’t Russian. Far from being the liberators and defenders of Europe it constantly tells us it is, the USA, having placed the combatant countries in their debt, arrived late to both World Wars once the victor was clear, and with the purpose of establishing a military foothold in Europe that it has never relinquished. The sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipeline between Russia and Germany that has forced Europe into energy dependency on the USA, and the waging of yet another US war on European soil this time (rather than its usual killing fields in the Middle East, South America and South-east Asia), announced clearly — to those who understand English — what the relation is between Europe and the US, which is that of colonised to coloniser.

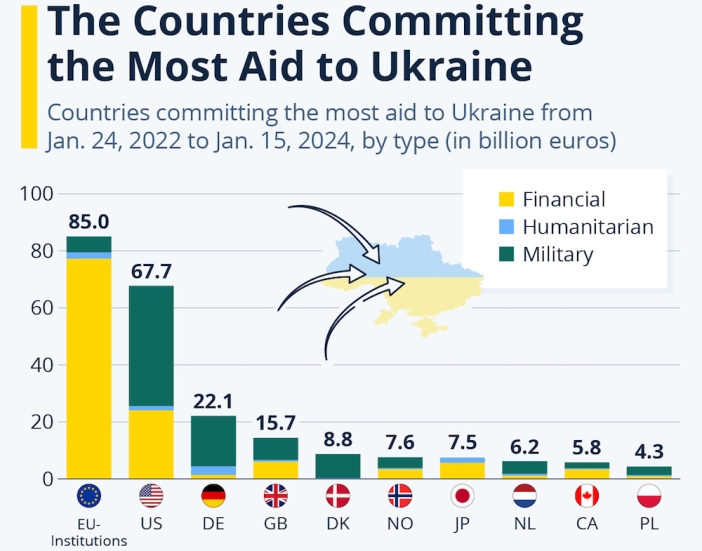

Europe, today, is under imminent threat of another invasion by the USA as it expands its military occupation of Europe — better known as the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation — eastwards to the last border with Russia. Indeed, by staying out of World War Two while selling arms and supplies to the UK and USSR, then putting war-devastated Europe in its debt for the next 50 years under the investment terms of the Marshal Plan, the US created a model of capitalist speculation in proxy-wars that, faced with its own $35 trillion of national debt today, it has revived in the Ukraine.

And yet, confronted by this history of US militarism, espionage and criminality and the logical conclusions to be drawn from it, American teaches us to repeat its idiotic mantras: ‘I stand with Ukraine’; ‘For as long as it takes’; ‘Russian aggression’; ‘Putin apologist’. This is the American language in the speech of US hegemony, and it is obediently and unquestioningly repeated by politicians, journalists and ideologues of US imperialism in the UK, Europe and across the West. There is, literally, no way to question this political hegemony in the American language, because American is the language in which we have been taught not to question, not to disagree, not to think, but instead to repeat, to agree, to comply.

3. The Orthodoxies of Not Thinking

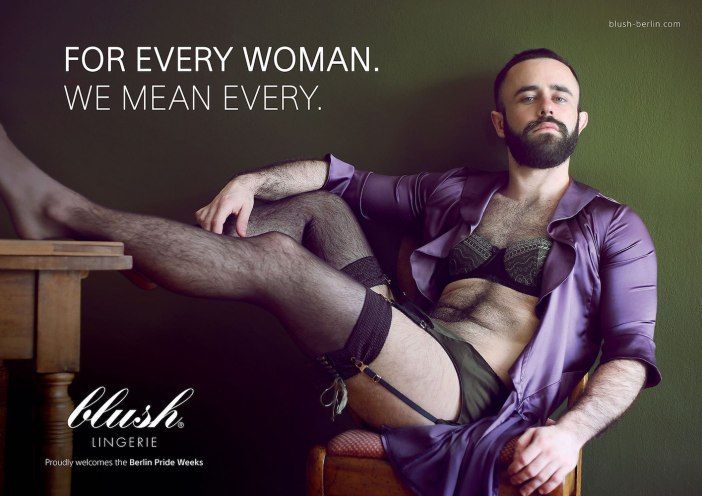

If American is the language of our indoctrination, woke is its lexicographer. It’s not by chance that the writing of woke into our laws and language — both what we are prohibited from saying and what we are compelled to say — is written in American. These include such woke terminology as ‘person of colour’ and ‘non-binary’, grammatically incorrect pronouns (‘they’ for he or she), fabricated prefixes (‘cis’, ‘trans’), or contested orthodoxies. These latter include, but are not limited to, ‘global boiling’ for cyclical changes in the earth’s climate; ‘pandemic’ for a viral disease with the infection fatality rate of seasonal influenza; ‘masking’ for the public demonstration of compliance, ‘social distancing’ for the prohibition of human interaction; ‘lockdown’ for the illegal removal of our human rights; ‘vaccine’ for experimental gene therapies; ‘long-COVID’ for the damage these cause; ‘gender’ for a consumer choice of sexual identities; ‘woman’ for a masquerade of femininity; ‘diversity’ for the censorship of differing views; ‘inclusivity’ for the criminalisation of non-compliance, and ‘sustainable’ for compliance with the policies and legislation of environmental fundamentalism.

We heard under lockdown how Americanisms both prohibited questions from the non-compliant (‘conspiracy theorist’, ‘covidiot’, ‘anti-vaxxer’) and provided a vocabulary in which the compliant could turn their cowardice, cruelty and stupidity into virtues (‘Stay Home’, ‘Protect the NHS’, ‘Save Lives’). And we’ve seen the same impoverishment of language used to silence opponents of everything from the privatisation of the world’s natural resources by global corporations (‘climate denialist’), the technocratic rule of national populations by the transnational apparatuses of biopower (‘COVID denialist’), the orthodoxies of transgenderism written into our laws and educational curricula (‘transphobic’), the immigration policies of the West (‘racist’), the neoliberalisation of the Ukraine (‘Putin apologist’), US imperialism in the Middle East (‘Hamas apologist’) to the crimes of the State of Israel (‘anti-Semitic’) and the even longer list of crimes of which the US is the perpetrator (‘anti-Americanism’).

American, in this respect, is the Newspeak of our time, the purpose of which, as George Orwell wrote in Nineteen Eighty-four, is to impoverish language, to remove all the words in which opinions prohibited by the state (for which he coined the prophetic term ‘thoughtcrime’) can be spoken, and in doing so to narrow the range of human consciousness. There’s a passage in Orwell’s novel that every speaker of English should refer to when they notice the intrusion of American into their speech, their reading, their thoughts. The scene is a discussion between the protagonist, Winston Smith, and an editor of the 11th edition of the dictionary of Newspeak:

‘We’re getting the language into its final shape — the shape it’s going to have when nobody speaks anything else. When we’ve finished with it, people will have to learn it all over again. You think, I dare say, that our chief job is inventing new words. Not a bit of it! We’re destroying words — scores of them, hundreds of them, every day. We’re cutting language down to the bone.

‘Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thoughtcrime impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller.

‘By 2050 — probably earlier — all real knowledge of Oldspeak will have disappeared. The whole literature of the past will have been destroyed. Chaucer, Shakespeare, Milton, Byron — they’ll exist only in Newspeak versions, not merely changed into something different, but actually changed into something contradictory of what they used to be. Even the slogans will change. How could you have a slogan like “freedom is slavery” when the concept of freedom has been abolished? The whole climate of thought will be different. In fact there will be no thought, as we understand it now. Orthodoxy means not thinking — not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness.’

We don’t have to recall the recently rewritten woke versions of Roald Dahl and Ian Fleming novels, or the fact that the UK Government’s anti-terrorism unit, Prevent, has placed Chaucer, Shakespeare and Milton on a list of books whose reading is flagged as an indication of ‘far-Right’ radicalisation, to demonstrate the realisation of Orwell’s predictions today. When we speak American we speak the language of our masters, of Washington, the US military, the CIA, of the United Nations, the European Commission, the World Economic Forum, of Google, YouTube, Facebook, X. The censorship mechanisms of social media, like the new legislation supressing our freedom of speech, aren’t there to stop us spreading ‘disinformation’; they’re there to change the way we think.

Again, as an example of which, in response to my first articulations of this argument on my X page, someone who uses a pseudonymous account wrote:

‘Sorry but this is a really stupid take. Many Americans possess a masterful command of the English language. We just speak it a bit differently than you Brits do. Language is a living thing that varies depending on geography and culture.’

In response, I pointed out that ‘Brit’ is an Americanism, derived from the Irish, who have more reason than most to hate the British. But my argument is about American, not Americans. Of course some Americans speak English well (not ‘good’, as they ungrammatically say). The point of my argument is that contemporary American is not a ‘living thing’ but a manufactured tool. As this response demonstrated, the corollary of being unable to speak is being unable to read. The readiness with which speakers of American — which includes, now, most of the British people under the age of 40 — cannot understand anything that deviates from its orthodoxies is another characteristic of woke, and further demonstrates its ideological purpose. This argument isn’t a ‘take’, as my critic described it, which connotes selecting an opinion from a set of predetermined choices, and is therefore another characteristic of US consumerism. It is an analysis of the linguistic structures of an ideology that has colonised most of the world, and which my interlocutor’s choice of word exemplifies.

4. US Exceptionalism

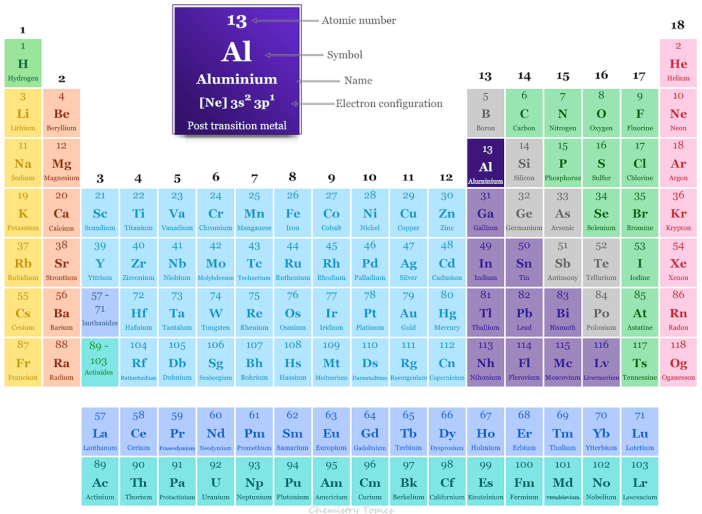

So, why do Americans say ‘aluminum’? Aluminium does not occur in metallic form in nature but is a compound found in almost all rocks, as well as in plants and animals. The word ‘alumina’, which refers to the oxide of aluminium, has been in use since 1595, when it was proposed by the German alchemist, Andreas Libavius, as the name for the as-yet-unidentified soil that formed the base of ‘alum’. Over two centuries later, in 1808, the British chemist, Humphry Davy, proposed to the Royal Society that the new elements he was attempting to isolate should be referred to as ‘silicium, alumium, glucium and zirconium’. Although he did not use ‘aluminium’, therefore, Davy recognised that the name of the new element, in common with the other elements, must contain the Latin suffix ‘ium’. This was unsurprising, since Davy had also coined the names ‘potassium’ and ‘sodium’.

New words, in order to have meaning in the language in which they’re spoken, must be made from the constituent elements of that language, whose etymology can be traced through the history of their emergence, coining and use. ‘Aluminum’ isn’t a variation: it’s the wrong word, in the same way that the animals Americans call ‘buffalos’ aren’t buffalos, which are significantly different animals that live in Africa and India. When words are separated from their history, they lose their consensual meaning. Or, more accurately, their meanings and referents are determined by those with the power to impose them on those required to speak them, whether they consent to or not. The meaning of words matter. Tens of thousands of Palestinian children have been killed by the Israel Defense (sic) Forces with complete impunity because the Western world has learned to respond to every accusation of genocide with the question: ‘Do you condemn Hamas?’

Confusingly, four years later, in Elements of Chemical Philosophy (1812), Davy used the word ‘aluminum’. Whether or not this was a typographical error, in 1828 Noah Webster, in his pointedly titled American Dictionary of the English Language, also used ‘aluminum’. In 1909, by which time the United States of America had surpassed the British Empire in its gross domestic product, Webster’s New International Dictionary — whose title signalled the intention of the USA to export its dominance of America to the rest of the world — noted that ‘aluminum’ was in common use in the USA in mining, manufacturing and trade, whereas ‘aluminium’ was preferred by chemists. Apparently happy with having two words with a single referent, by 1934 Webster overcame this anomaly by describing the latter as ‘especially British’. This effectively consigned ‘aluminium’ to the dustbin of history the US was beginning to write. So although, as recently as 1990, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry — a federation formed for the advancement of the chemical sciences, including nomenclature and terminology — made ‘aluminium’ the international standard, Webster continues to use ‘aluminum’.

It may be no more than a symptom of the fact that the notoriously tongue-tied Americans can’t get their mouths around a five-syllable word without having to remove their gum; but this retention of ‘aluminum’, I would argue, is the linguistic equivalent to the US, against the votes of the other members, vetoing UN Security Council Resolutions for a ceasefire in the Gaza Strip four times while delivering more than 100 separate arms deals to Israel since 7 October, 2023; or, in 2018, threatening to arrest judges from the International Criminal Court if they pursued an investigation of US military personnel for war crimes committed in Afghanistan; or, in 2020, imposing sanctions against two ICC judges for investigating human rights violations by the US military; or again, this year, US Senators threatening to ‘target’ members of the International Court of Justice who issued arrests for the Israel war cabinet responsible for the genocide in Gaza.

The correct spelling of ‘aluminium’ only matters to those who care about language and perhaps about the consensual basis to scientific method; but the imposition of American exceptionalism on the rest of the world at the point of a gun and now the threat of nuclear war should be of concern to all of us. American is the tool for the cultural and political construction of the West by the USA, a product of its financial power to sanction those individuals, organisations and nations that don’t comply, and the justification for its arrest, assassination, overthrow or military invasion of those who dare to resist. To use the appropriate Americanism, the USA doesn’t ‘do’ consensus.

Simon Elmer

One thought on “American Newspeak: US hegemony, woke lexicography and the end of thinking”