At the invitation of the Architecture Society of the University of Cambridge, it was announced that, on 13 May 2019, Patrik Schumacher, the Principal at Zaha Hadid Architects, gave a lecture titled ‘Architecture and Urbanism in the 21st Century’ in the Department of Architecture. In response, a group of postgraduate students invited Architects for Social Housing to give a presentation that would introduce students to the writings of Patrik Schumacher. ASH presentation was in two parts: the first offering a critique of Patrik’s various statements about UK housing provision; the second presenting an alternative model of architectural practice to the neo-liberal architecture of Schumacher’s Parametricism. We titled our lecture ‘For a Socialist Architecture.’

1. The Duties of an Architect

In December 2015 the International Trade Union Confederation predicted that 7,000 construction workers will die on building sites in preparation for the 2022 Football World Cup in Qatar, where 1.8 million migrant workers from India, Nepal, the Philippines, Egypt, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan are kept in conditions of semi-slavery, with pay withheld, their passports confiscated, living in cramped work camps and labouring in 50 degree heat. In contrast, Qatar’s 278,000 citizens have the highest per capita income in the world. When criticised for the conditions of these workers in relation to her design for the Al Wakrah football stadium (above), one of eight being built for the tournament, Zaha Hadid responded:

‘I have nothing to do with the workers. I think that’s an issue the government should pick up. It’s not my duty as an architect to look at it.’

Regardless of the fact that Zaha Hadid Architects’ project hadn’t gone on site yet, so neither the practice not she personally could have been responsible for any of the estimated 1,200 deaths at that time (although construction workers have died on the Al Wakrah site since), ASH argues that the basic sentiment Hadid expressed goes against the principles of a socialist architecture. Indeed, the first principle of a socialist architecture must be to look – as Hadid is not alone in refusing to do – at the sources of funding, labour relations and working and living conditions under which their architecture is being produced, and take into consideration all those who will produce and use that architecture.

But if we can’t look to so-called ‘Starchitects’ like the late Zaha Hadid to give social guidance to architectural practice, can we look for it in the architectural establishment, and specifically to the Code of Conduct drawn up by the Architects Registration Board? If we did, we would find that, rather than promoting practices with social value, over the past two decades the ARB has been gradually removing any reference to the social impact of an architect’s work. The ARB Code of Conduct 2002 at least mentions taking in to consideration the people ‘who may reasonably be expected to use or enjoy the products’ of an architect’s work (end users, residents, neighbours, etc);

‘In carrying out or agreeing to carry out professional work, Architects should pay due regard to the interests of anyone who may reasonably be expected to use or enjoy the products of their own work. Whilst Architects’ primary responsibility is to their clients, they should nevertheless have due regard to their wider responsibility to conserve and enhance the quality of the environment and its natural resources.’

However, following the revision of this duty in the Code of Conduct 2010, any reference to people has been removed and refocused on the environment:

‘Whilst your primary responsibility is to your clients, you should take into account the environmental impact of your professional activities.’

Which leads us to the Code of Conduct 2017, the current version, which has the following:

‘Where appropriate, you should advise your client how best to conserve and enhance the quality of the environment and its natural resources.’

Standard 5, moreover, is the shortest code of all, comprising only a single sentence, while Standard 4, in contrast, on the ‘Competent management of your business’, has 6 points and takes up an entire page. These revisions have effectively allowed the substitution of the architect’s ‘regard’ for people with, first, ‘taking into account’ the impact of their work on the environment, and, finally, ‘advising the client’ on how to conserve the environment. Is it any wonder Zaha Hadid did not see it as her duty to ‘look’ at the workers (shown above) constructing the Al Wakrah stadium she had designed? The ARB’s erasure of any human presence for consideration other than that of the client from the duties of an architect, and the decline of those duties from responsibility for the use of their work to the considerations of an accountant and a consultant, tells us a lot about what ground – both moral and statutory – has been yielded by the profession.

The duties of an architect don’t end with the construction or completion of the building; and the more an architect understands how buildings, communities or a neighbourhood work in practice, the better their architectural solutions will be. An ongoing relationship, therefore, with both the client and those expected to use the architecture (as ASH has with residents of the Patmore Co-operative above), is always preferred. In this respect, I’ve never understood how prizes can be awarded for buildings that have only just been completed, when in many cases those buildings quite rapidly reveal fundamental flaws. This is the case with the award-winning Bridport House, designed by Karakusevic Carson Architects as part of the regeneration of the Colville estate in Hoxton. Celebrated as the first council housing to be built in Hackney in four decades, 7 years later Bridport House is under scaffolding for repairs throughout 2019, and every resident has had to be rehoused while engineers establish whether the building can be repaired and whether the cladding meets fire-safety regulations.

Contrary to this indifference of the profession to the producers, users and uses of an architect’s work, ASH maintains that a socialist architecture is one in which the processes of funding, procurement, design, construction, management, maintenance, use and re-use of the architecture take precedence over the purely formal qualities of the architectural object. Architects often argue that they are called in, much like doctors in the middle of the night, to fix a problem and are given little influence on the brief or the parameters of the questions they are paid to solve. A socialist architecture must be critical of, and involve itself in, the development of a client’s brief, and where necessary be prepared to reject the commission when it fails to meet the standards practitioners of a socialist architecture must set for themselves.

2. Refurbishment versus Demolition

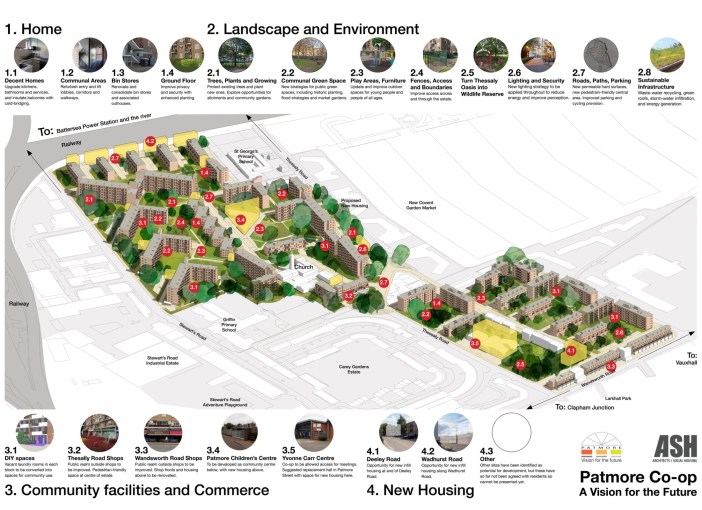

For the past two years ASH has been working with the Patmore Co-operative in Wandsworth to come up with a ‘vision for the future’ of the estate. Although not directly threatened with demolition yet, the estate is in the middle of the Vauxhall, Battersea, Nine Elms Opportunity Area, and has been starved of investment for years. Our proposals, accordingly, bring together an array of works to the homes, the landscape, the environment and the communal facilities. Many of these proposed works – such as the re-purposing of disused laundry rooms across the estate as collective ‘DIY spaces’, or new lighting schemes – are small adjustments, but are essential to the future success of the estate and the sense of pride and collective identity residents wish to recover. How a building is maintained, how it will evolve over time, how it is looked after, used and re-used are all intrinsic to a socialist architecture.

The obvious way to fund the homes for social rent that constitutes that greatest housing needs in the UK is for the Government to invest in it sufficiently, as it should any essential infrastructure, thereby removing new-build housing provision from the market altogether. In the absence of such funding, however, or anything like it, ASH has found itself asking whether a socialist architecture can exist within a capitalist system; and, if it can, what would it look like? The key to answering this question lies in the way in which projects are financed. One of the first things residents are always told by local authorities embarking on estate regeneration schemes is that there simply aren’t the funds available from central government to refurbish the estate or build the new homes Londoners need. The only option, the council decides in advance, is demolition and redevelopment.

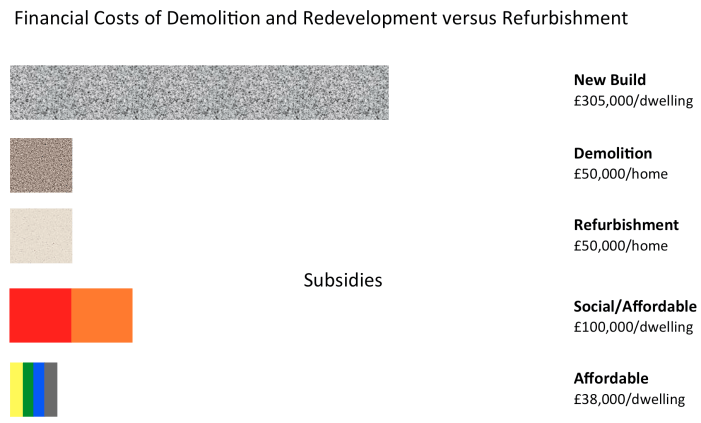

However, ASH’s research into the costs of estate regeneration shows that the eventual tenure of the homes that are built on an estate regeneration project are dictated entirely by this prior and unilateral decision to demolish the existing estate; and that what is consistently being built in place of our demolished council homes is not housing that the majority of Londoners can afford either to rent or buy. Given the costs of compensation for residents, of the demolition of the existing estate, of the construction of the new development, of the profits demanded by the private developers, contractors and investors, and the insufficient Government funding for socially rented housing, at least 50 per cent of a new development must be for market sale, with the remainder being a mixture of affordable homes, around half of which are typically for shared ownership, with the resulting mass loss of homes for social rent. Indeed, the demolition and redevelopment of structurally-sound council housing requires such a huge financial commitment that every local authority or housing association undertaking such a regeneration scheme is effectively betting on house prices rising in order to fund the redevelopment in the form of cross subsidisation, which in turn inflates house prices even further.

ASH’s response to this is simple. Do not demolish structurally-sound dwellings in which people have made their homes and communities, but refurbish them and – where possible and with the consent of the residents – increase housing capacity on the estate with infill and roof extensions. The fact that the cost of demolition is equal to or more than the cost of refurbishing a home up to the Decent Homes Standard plus should be argument enough that, as an option for regeneration, demolition does not make financial sense for public bodies interested in housing rather than property prices.

The architectural profession’s current culture of demolition and redevelopment – of the erasure of the historical layers of the city and the construction of the always new commodity – is driven not by concern for the most efficient solution to a brief, but by the desire to make and maintain a name for an architectural practice with a recognisable brand or – when that brand has already been established – to meet the developer’s desire for a signature building, whether it’s the by-now identikit Meccano of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners, the curvilinear latticed facades of Foster + Partners, or the parametric blancmanges of Zaha Hadid Architects, which behind the infinite variety of their computer-generated forms all belong to an instantly identifiable commodity brand. A socialist architecture, by contrast, subordinates such marketing concerns to the use and function of the building in meeting the total requirements of the scheme; and in estate regeneration the decision not to demolish, but to refurbish, to improve, and where possible to add, must be the default point of departure.

3. The Total Costs of Architecture

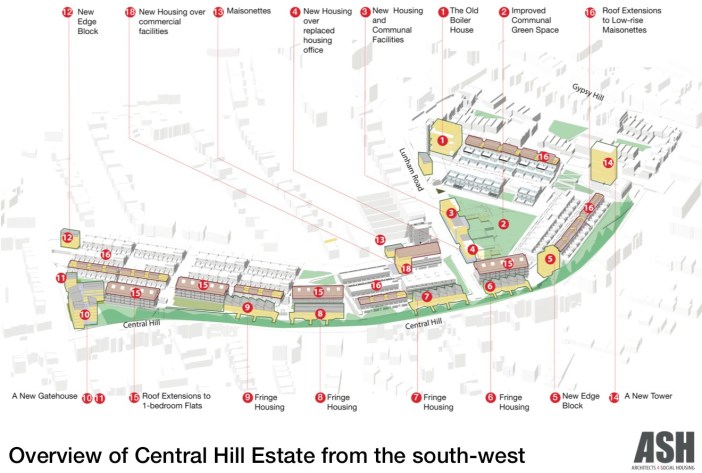

Central Hill estate in Crystal Palace (above) was designed in the 1960s by Ted Hollamby and Rosemary Sternstedt around the existing trees and steep landscape. It is made up of pedestrian pathways, off which pairs of stacked maisonettes are arranged across the South London hillside, with each home having the same view of Central London to the north and a courtyard facing the sun to the south. Designed to the socialist principles that had currency in Lambeth’s Architecture Department at the time, the estate maximises its relationship to both the landscape and the environment, and is very popular with the residents, who enjoy the variety of private and communal outdoor spaces, while also achieving a high density of housing unusual for such a low-rise estate.

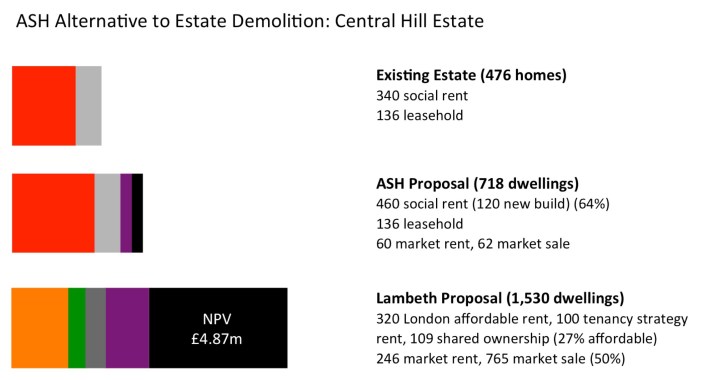

Central Hill estate consists of 456 homes ranging from studio flats to 6-bedroom houses, plus communal facilities that include a communal green, shops, a sports court and community hall. The entire estate is currently condemned to demolition by Lambeth Council, which has proposed redeveloping the estate via a special-purpose vehicle called ‘Homes for Lambeth’. This is a wholly-owned but private company with which the council plans to build around 1,500 new dwellings on the site, half of which will be for market sale, and the remainder an assortment of market rent and various ‘affordable’ tenures, including shared ownership, tenancy strategy rent and the London Mayor’s new London affordable rent (above). Under these plans, the existing 340 demolished homes for social rent will be replaced by 320 homes for London affordable rent, which according to the London Renters Union is on average 60 per cent higher than social rent. So even in the unlikely event that existing council tenants, currently on secure tenancies, return to the estate once the redevelopment is complete in 5, 10 or 15 years time, it is highly unlikely they will be able to afford the increased rents and service charges, and would now be living in a housing association, which under existing legislation cannot issue tenants secure tenancies.

In contrast to this proposal, the feasibility study for which was designed by PRP Architects, ASH’s proposal retains and refurbishes all the existing homes, keeps as many of the existing trees as possible, while making all necessary improvements to the landscape and community facilities. Priced by quantity surveyors Robert Martell and Partners at £97 million, the ASH proposal would be paid off in around 25 years by the social rent and market sale – in roughly equal measures – of the new-build dwellings. The end result of the ASH scheme would be an increase in the number of home for social rent (indicated in red above), and nearly 50 per cent more (140 homes) than even Lambeth council’s proposed quota of London affordable rent (indicated in orange).

In addition to this increase in homes for social rent, ASH’s proposal identifies the possibility for a total of 242 new homes on Central Hill estate – an increase of around 50 per cent on the existing provision. Infill housing (indicated in yellow above) would be built on unused and derelict sites; while roof extensions (indicated in pink), consisting of one or two additional light-weight prefabricated floors on top of some of the existing flats, would be located on the edges of the estate where they do not obscure existing views and sight-lines.

Issues that residents have with the existing layout or design of the estate have also been addressed through refurbishment and thoughtful interventions. These include reinforcing the edges of the estate with a series of taller edge-blocks, with strips of housing along the perimeter roads providing wheel-chair access accommodation and improved access onto the estate; the consolidation of community facilities in order to increase the communal green space in the centre of the estate; the re-use of an existing disused boiler house; and the refurbishment of the existing homes and landscape, both of which have been run down by the council through a process of managed decline over the past decade.

In contrast to the estimated total cost of £97 million for the ASH proposal, the cost to Lambeth council just to demolish and rebuild the 456 existing homes would be over £200 million, more than twice the cost of our entire proposal; while to match the 718 dwellings the ASH proposal provides would cost nearly £300 million, three times the cost of our scheme. In order to recoup these costs, however, the Lambeth council proposal of 1,530 new-build dwellings, of which half would be for market sale at upwards of half a million pounds each, would cost over £570 million, paid over a 60-year span, which is more than twice the time of the ASH proposal.

It’s no surprise, therefore, that we have recently heard that Lambeth council are now having second thoughts, and may be going back to re-start their 5-year, £1 million consultation with residents all over again, though with the intention, this time, of genuinely looking at a refurbishment and infill option. ASH’s in-depth case study of the Central Hill regeneration, which includes both our own proposal and that of Lambeth council, demonstrates that, even within the current economic and political climate, with the lack of funding and disastrous policies, it is still entirely possible to finance a socialist architecture that will build, rather than demolish, the homes in which Londoners can afford to live.

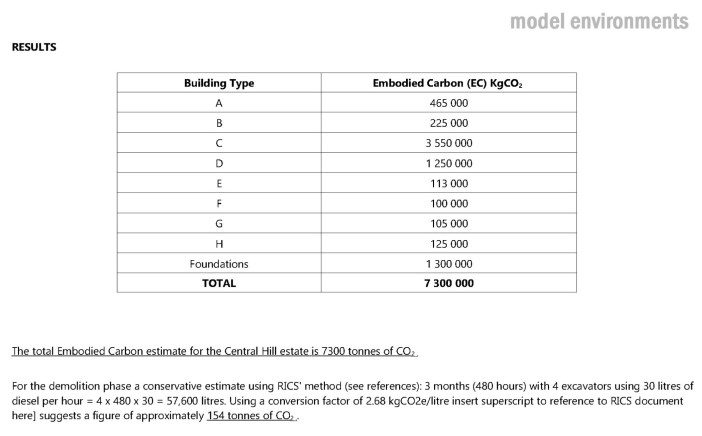

But in addition to the huge financial costs and debt risk associated with demolition and redevelopment, the environmental costs of both are huge, ranging from the loss of the embodied carbon in the existing buildings to the pollution in the air from demolition, to the environmental impact of the new buildings. To estimate what these are, ASH commissioned a report by engineers Model Environments, who calculated that:

‘A conservative estimate for the embodied carbon of Central Hill estate would be around 7,300 tonnes of CO2e, similar emissions to those from heating 600 detached homes for a year using electric heating, or the emissions savings made by the London Mayor’s RE:NEW retrofitting scheme in a year and a quarter. Annual domestic emissions per capita in Lambeth are 1.8 tonnes. The emissions associated with the demolition of Central Hill estate, therefore, equate to the annual emissions of over 4,000 Lambeth residents.’

As Chris Jofeh of Arups engineers has testified, it would take at least 30 years for the more environmentally efficient buildings one might expect to be built on new developments to recoup the environmental losses caused by the demolition of existing estates. So if both local authorities and central government are serious about a commitment to reducing carbon emissions, stopping existing and future demolition schemes must be at the top of their list of actions.

A commitment to the environment and to policies of de-growth is inevitably a socialist concern, not least because damage to the environment has enormous collective social and economic consequences; but also because only a socialist economy can hope to re-order the relations of production to sustainable levels of consumption. Under capitalism, the global consequences of expansion are not estimated in individual project costs but deferred, manifesting themselves in the health or social well-being of future generations, or in contributions to the long-term destruction of our global environment. The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, makes a start in asking all public bodies to consider the social and environmental impact of what they do. A socialist architecture must similarly calculate and mitigate the social and environmental costs of a project.

When working on an estate regeneration scheme, architects must produce an impact assessment of the financial costs, to the council and residents, both existing and future; the social costs, for existing residents of the estate as well as those who live in the neighbourhood and will be affected by any new development; and the environmental costs, not only of the embodied carbon lost, but the carbon emissions from demolition and construction, and the environmental impact of the use of additional buildings, in terms of both energy use and carbon emissions from, for instance, increased car use, as well as the impact on local services, such as roads, schools, clinics, hospitals, police and fire services. Such impact assessments are different from a financial viability assessment calculating the net present value of an estate against possible future returns; or calculating, for example, the additional income to the chain stores and supermarkets that will benefit from the gentrification of a neighbourhood consequent upon building high-value property in the area; or again the rise in house and land values for property- and land-owners who will benefit according to what Savills estate agents has calculated as the land value uplift in an area consequent upon the demolition and redevelopment of its council estates.

4. Use Value versus Exchange Value

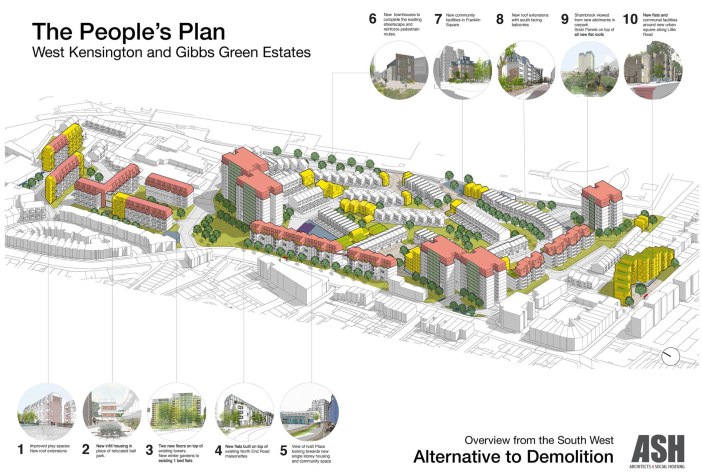

West Kensington and Gibbs Green (above) are two adjoining council estates in the London borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. Comprising around 760 homes completed between the 1950s and the 1970s, the buildings range from 4- to 5-storey blocks of maisonettes to 11- to 12-storey point blocks and 2 to 3-storey townhouses, all of which are home to a strong community of around 2,000 residents. However, following the council selling the land to the developer Capco, and the ensuing threat of demolition and redevelopment, the residents of West Kensington and Gibbs Green Estates formed a Community Land Trust, and in summer 2015 approached ASH to carry out a feasibility study for the refurbishment and improvement of their estates. This study forms the central part of their application to the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government for the Right to Transfer the two estates into their own ownership, and in doing save them from demolition.

ASH’s feasibility study demonstrates that we are able to add up to around 327 additional homes to the existing estate (around 40 per cent of the existing total) without demolishing a single home (above). These proposals have been costed, and a viability assessment has confirmed that the funds from the sale and rent of the new homes, added to the government subsidies for affordable housing provision, would pay for the construction of the 327 new-build dwellings, the refurbishment of all 760 existing homes, as well as the improvements to the landscape and community facilities that were identified by over 200 residents over 6 months of design workshops.

ASH’s designs proposals include refurbishment of, and new roof extensions (above) to, the low-rise maisonettes and point blocks, plus the addition of winter gardens that would provided additional space to the 1-bedroom flats in the point blocks.

ASH also proposed designs for a number of single-storey, sheltered housing for elderly or disabled residents (above). These would free up some of the larger homes on the estate that are currently under-occupied, which could in turn be used to house over-crowded households elsewhere on the estate. Over- and under-occupation, which is regularly cited by councils as a reason to demolish housing estates, is nothing of the sort, and can easily be addressed through infill development responsive to the housing needs of residents.

ASH also proposed new infill-housing above an existing carpark on the estate (above), with a new community facility below.

Finally, on the site of the current community centre, new high-density housing blocks (above) would provide a new entry to the estate around a public square and communal or commercial facilities on the main road.

ASH’s proposal enables residents to remain in their homes and communities rather that being scattered across the borough or further afield, which will be the inevitable result of the developer’s proposal for demolition and redevelopment; so this is clearly the most socially, as well as environmentally and financially, sustainable option for the future of the estate community. Again this demonstrates that, even within existing economic conditions, it is entirely possible to produce a socialist architecture that is financially viable, and which works with the community and environment, and not against it. The residents’ Right to Transfer application is currently under consideration by the Secretary of State, and four years after ASH was brought into the campaign both estates are still standing.

In contrast to the ASH proposal, the properties proposed by Capco developers, which have already been built on phase 2 of the development, were advertised at £800,000 for a 1-bedroom apartment, £1.2 million for a 2-bedroom apartment, and £1.7 million for a 3-bedroom apartment. And when the projected value of the properties on the future developments fell following Brexit, Capco responded by proposing a further increase in the number of overall properties, built at higher densities and with correspondingly greater environmental impact, in order to recover their anticipated revenues, with no consideration of the further deleterious impact on the existing residents or the surrounding area. In this can be seen, once again, the inadequacy of the supply and demand model of housing provision, which is exposed not as a mechanism for reducing house prices, but as an excuse for increasing the profits of developers and investors. A socialist architecture, in contrast, must look at the use-value of the buildings as, in this case, homes, and not merely at their exchange-value as commodities.

5. Users versus Client

I’ll now discuss briefly some of the other projects ASH has worked on, and which have had some positive outcomes. In 2015 residents of Knight’s walk in Kennington, South London, were desperate, having been informed by Lambeth council that the only option for their homes was total demolition. Knight’s walk is, in fact, not a separate estate but forms the low-rise component of the Cotton Gardens estate, which comprises a range of housing typologies, including three point-blocks of 1- and 2-bedroom maisonettes, as well as, originally, 3-bedroom townhouses. During the lead-up to the regeneration process, Knight’s Walk, which is largely composed of 3-bedroom bungalows together with some 1-bedroom flats, was isolated from the rest of the estate and taken out of the larger context, so that the council could argue that the buildings were too low-density and therefore must be demolished to make way for increased density.

Working with the predominantly elderly and disabled residents, ASH demonstrated that we could add an additional 80 dwellings to the existing 33, without demolishing a single home. All the proposed new-builds were lightweight, prefabricated modular units, dual aspect, and met all the local planning regulations such as the right to light and privacy of existing residents. Even though Lambeth council didn’t adopt ASH’s scheme, as a result of our proposals the council retracted its full demolition scheme, and half the estate has been saved from demolition.

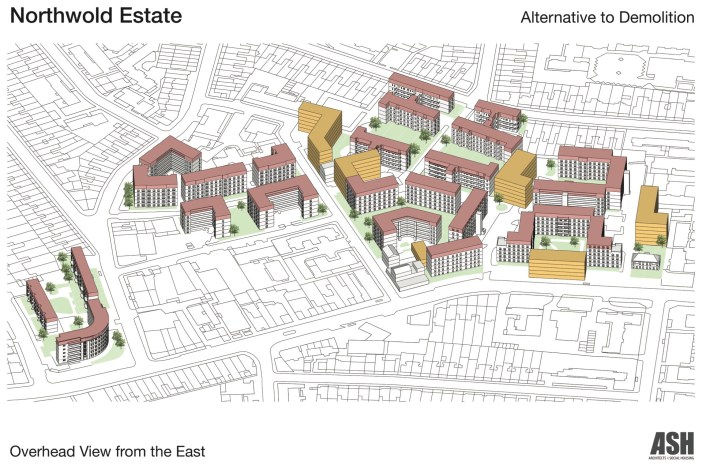

On our proposals for the Northwold estate in Hackney, ASH again demonstrated that we could increase the capacity of the existing estate by over 40 per cent without demolishing any of the existing homes. Indeed, the 245 additional homes we were able to add to the existing 580 was identical to the number of homes that Guinness Trust, the landlord, were planning to add through the demolition and redevelopment of half the estate. Unlike these, however, at least half the dwellings proposed by ASH could be for social rent, while the cost of demolishing the 154 homes targeted by the Guinness Trust would mean at least half their replacement would have to be for market sale. Like Lambeth council the Guinness Trust have now cancelled their plans to demolish the Northwold estate, and are also now pursuing an infill and refurbishment scheme very similar to the one proposed by ASH.

In contrast to the infill possibilities established by ASH, TM Architects, who were employed by the Guinness Trust to draw up the options for the regeneration of the Northwold estate, found room for only 40-60 new dwellings in their infill option, compared to the 245 found by ASH. It seems clear that they had been instructed by the client that this option was not to be properly explored, but merely used as a tick-box exercise to convince residents this possible solution had been considered and dismissed. Unfortunately, this is common practice among architectural practices engaged in estate regeneration schemes. ASH was told by one young architect who had just graduated that, by himself, his practice had given him the brief for a similar infill option, and allocated a single day in which to produce it. Clearly, such abdication of the duties of an architect toward the users of their product – in this case the existing and future residents of the Northwold estate – is socially (and perhaps morally and legally) indefensible. A socialist architecture, by contrast, must always interrogate the client’s brief, and take responsibility for producing the option best suited to the needs of the users of their architecture.

6. Community-led Housing

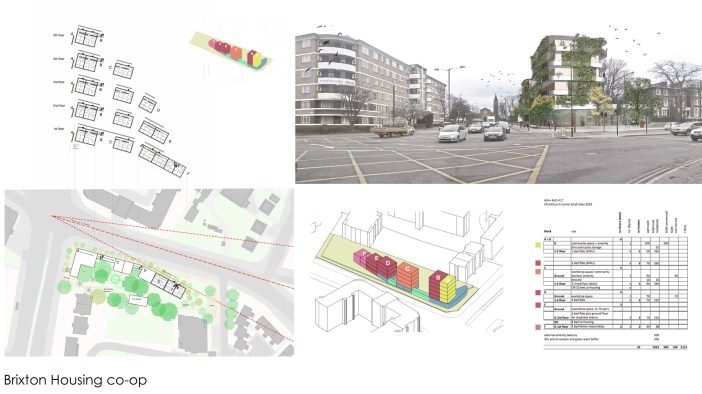

Over the past two years ASH has also been exploring new forms of housing provision. This is our proposal for the Mayor’s Small Sites x Small Buildings scheme, on which we collaborated with Brixton Housing Co-operative in 2018. This scheme was launched by the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, supposedly in order to give community-led housing groups the opportunities to bid on small parcels of TFL land across London.

Co-ops for London introduced ASH to the Brixton housing co-operative with a view to collaborating on a submission for the Small Sites x Small Builders scheme, and we identified a stretch of brownfield land located that had become available on the edge of Brixton in South London, and which the GLA had specified must be 100 per cent ‘affordable’ housing. The Brixton Housing Co-op is a long standing Brixton co-operative with a high percentage of elderly, LGBT and BME residents, communities on whom the gentrification of Brixton is having a disproportionately negative effect, and this site was exactly what they were looking for in order to expand their housing capacity and serve their local community.

Our proposal, which we named Brixton Gardens, occupied the northern edges of the site, which is on the edge of the South Circular. The buildings incorporated a community hall and workshops on the ground floor that would be for low-cost rent for the local community, and accommodation ranging from 3-bedroom family maisonettes, 1- and 2- bedroom flats, and an 8-10 bedroom co-housing unit, all sharing a south-facing communal garden.

Inspired partly by the Mietshäuser Syndikat in Germany, in which co-operatives pool resources across member co-ops, the project would be primarily funded by the Brixton Housing Co-op, which had access to capital from their existing housing stock in Brixton. Through the creation of a community land trust whose members were housing co-operatives, our proposal would gain the benefits of the CLT by putting the land in trust, while managing the homes as co-operative, socially-rented homes. This differs considerably from the majority of homes developed by CLTs, which are typically for shared ownership schemes, and therefore, although officially ‘affordable housing’, far beyond the reach of most people on London’s council housing waiting lists. By contrast, housing co-operatives are composed of low-cost rental accommodation, the tenancy type in most demand in London, and it was this we proposed building on Brixton Gardens.

Unfortunately, the ASH/Brixton Co-ops bid was not successful. The reason, we were told, was that we simply hadn’t offered enough money for the land. Given the ‘community-led’ banner under which the scheme was being promoted and funded by the London Mayor, we assumed that the judging criteria would take into account the social, economic and environmental benefits the project would provide for the local community, but this turned out not to be the case. The fact our scheme accommodated a wide provision of community facilities and was to be 100 per cent for social rented, while the winning scheme proposed 100 per cent properties for shared ownership and is therefore targeted at middle-income owners, apparently played no part in the estimation of the relative bids. If the London Mayor is serious about supporting community led development, then criteria that acknowledges the social and economic benefits such a scheme is offering must be factored into the allocation of rare public land, above and beyond the purely economic offer on the land.

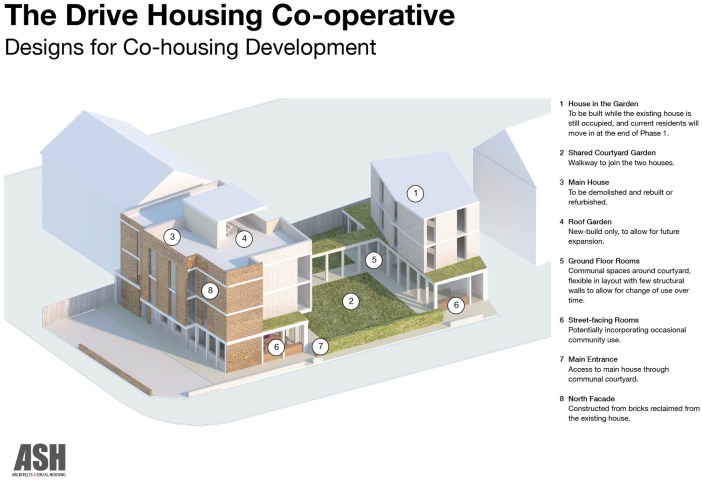

And finally, over the past 18 months ASH has been working with a co-housing co-operative in North London to double the size of their existing housing capacity by accommodating an additional twenty residents, with all tenancies at social-rent levels. Co-housing is emerging as an economically efficient and socially beneficial way of providing low-cost housing. Although typically sharing a range of communal facilities, co-operative co-housing differs from ‘micro homes’ in that the former’s housing is rented, not sold, and owned collectively, not privately, by residents who share the responsibility for its construction, design, management and maintenance.

It is important that ‘community-led housing’ is not allowed to become just another term in the increasingly duplicitous lexicon of UK housing policies designed – like ‘affordable housing’ and ‘estate regeneration’ itself – to hand public land and funding over to private developers and investors, but uses that public land for the benefit of the community of users. To this end, a socialist architecture must apply pressure on both the Greater London Authority and the UK Government to write policy and legislation that will make it possible to pursue socialist practices further within our current capitalist system. Voting for this or that political party or waiting for changes in legislation or policy isn’t enough when there is a cross-party consensus on the marketisation of housing provision.

7. For a Socialist Architecture

Among the various roles that together make up the building industry, all of whose interest in that industry are primarily commercial, only the architect has a duty of care to the users of its products, and not just their customers. As we are witnessing in the public inquiry into the Grenfell Tower fire, clients and contractors can point to inadequate and failed building regulations to excuse their abnegation of responsibility for their work. But a socialist architecture must have a duty beyond meeting policies specifically designed to remove any curbing of market forces: a duty that begins with the well-being, safety and lives of the users of their products and extends out to encompass the total social, financial and environmental impacts of the work in which they participate from its inception and construction through the whole lifespan of its use and re-use.

A socialist architecture is one that priorities residents and users over the profits of developers; recognises that the question of how to save the environment is an economic question and that the architecture of Neo-liberalism is contributing to its destruction; and that, within the specificity of the estate regeneration scheme, it is possible to design for the housing needs of communities as well as significantly increasing the number of homes for social rent on existing estates even within the existing economic system. Hopefully, with Brexit threatening global speculation in the UK property market and the environmental and social consequences of doing so becoming harder and harder for politicians to ignore, councils will start to realise that, rather than further deregulation of a market made dysfunctional by global capital investment, these alternatives are the most socially, financially and environmentally sustainable answer to London’s crisis of housing affordability. In summary:

- A socialist architecture must be critical of, and involve itself in, the funding, procurement, design, construction, management, maintenance, use and re-use of its product, which must take precedence over the purely formal qualities of the architectural object.

- A socialist architecture must take the refurbishment of existing homes, the improvement of communal amenities and, where possible and with the agreement of existing residents, the infill of additional housing as its default option in any estate regeneration scheme, rather than the current orthodoxy of demolition and redevelopment.

- A socialist architecture must consider the impact of, and respond to, the social, financial and environmental costs of its product, to both users and those affected by it, from the moment of its proposition through the lifetime of its use and after.

- A socialist architecture must prioritise the use-value of its products over their exchange-value as commodities.

- A socialist architecture must interrogate the client’s brief, and be prepared to reject a commission when it fails to produce the option best suited to the needs of the users of its products.

- A socialist architecture must apply political and cultural pressure for the legislative and policy changes that will make it possible to further socialist practices within our current capitalist system.

This summer ASH will be taking up a month’s residency in the 221a Gallery in Vancouver, Canada, where we plan to further formulate what we have learned from the practices of ASH and other architects into principles For a Socialist Architecture. Under this title, this text will be published by the gallery and made available to council estate residents facing the demolition of their homes, to policy-makers looking for alternatives to selling off what’s left of our public land and housing for private investment, and, yes, to architects wondering if there is an alternative to the Brave New World that is all-too-familiar of Patrik Schumacher.

Architects of the world, unite! You have nothing to lose but the manacles you are forging for your own hands.

Geraldine Dening and Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

P.S. A Note on Terminology. ASH is trying to formulate what a socialist architecture would be under capitalism. The advancement of the estate regeneration programme and the state of the housing crisis means it’s far too late to wait around for the promise of socialism from neo-liberals masquerading as social democrats (i.e. the Labour Party). But we’ve also taken care not to refer to ‘socialist architects’. Even though many of the architects of UK council estates were explicitly socialist (George Finch, Kate Macintosh, Denys Lasdun, Ralph Erskine, Neave Brown, Ernö Goldfinger), or even communist (Ted Hollamby, Berthold Lubetkin), nowadays, after forty years of neo-liberal propaganda, most architects seem to equate socialism with either Stalinist totalitarianism or, alternatively, social-democratic liberalism. We’re not interested in identities (the Labour-voting housing activists who identify themselves as ‘anarchist’ or ‘socialist’), but in practices. A socialist architecture is not dependent for its existence upon a socialist government, a socialist economic system or even socialist architects. It’s existence is manifested through practice alone. So, hopefully, whether or not an architect identifies personally as a ‘socialist’ (whatever that may mean to them), ASH formulating the principles of a socialist architecture will show that it is possible to practice architecture as something other than the obedient tool of capitalism with its fingers crossed for the election of Jeremy Corbyn (and other get-out clauses of middle-class bad faith).

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

Interesting items! Some 50 years ago, I was building a medium-rise office building in Thailand when 7 workers died while they were dismantling bamboo scafolding on completion of the building. They were playing the fool, pretending to be monkeys when one of them, who was not participating in the fun, cut a key joint. The whole lot collapsed. I was severly shocked and I got the quantity surveyor to put into all future contracts a warning about ‘taking all due care about dismantling items, about demolition work, scaffolding erection and dismantling and erecting and removing cranes and the requirement that full details of this kind of work should be submitted to the architect and/or the engineer for approval. Interestingly, this is now a legal requirement by the local authorities. Accidents still happen and contractors have gone to jail for negligence.

On a different note, on another building project in Thailand, a murder occured on a building site and all work stopped for a week because the workers refused to continue work until the Brahmins had conducted an exorcism of the poor victim’s spirit. Again, I asked the QS to insert a suitable clause into all future contracts to cover exorcisms. He assured me that this was the first time ever, that a QS had to write such a clause. Certainly, Schumacher has moral obligation to ensure that all normal health and safety regulations should be followed as a contractual obligation.

Best Wishes, David Russell

LikeLike