1. The Estate Regeneration Programme

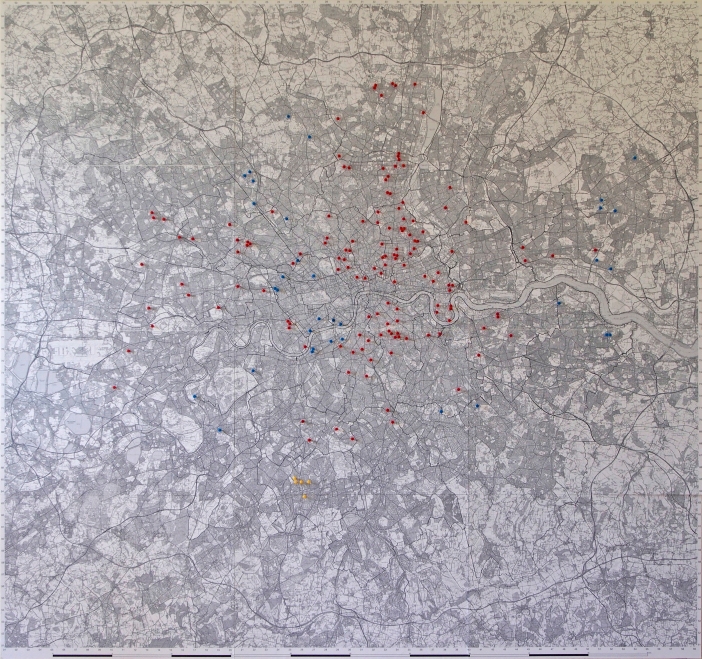

In September 2017, as part of our residency at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, Architects for Social Housing (ASH) mapped out London’s estate regeneration programme. Our research identified 237 housing estates that have recently undergone, are currently undergoing, or are threatened with regeneration, demolition or privatisation with the resulting loss of homes for council or social rent. In one borough alone, no less than 9,500 such homes are being lost to Southwark council’s estate regeneration programme. These figures are not anomalies, but accord with the targets of estate regeneration. These have been laid out in such policy-defining publications as City Villages: More homes, better communities (published in March 2015), which recommended reclassifying existing council estates as ‘brownfield land’ – a term usually applied to ex-industrial or commercial land that requires decontamination before use; and the report to the Government’s Cabinet Office titled Completing London’s Streets: How the regeneration and intensification of housing estates could increase London’s supply of homes and benefit residents (January 2016), which recommended demolishing the council homes of over 400,000 Londoners. In practice, if not in name, the estate ‘regeneration’ programme means the demolition and redevelopment of housing estates for capital investment by offshore companies, buy-to-let landlords and home ownership. Only a small percentage of the new-builds end up as so-called ‘affordable’ housing, and this newly designated category increasingly means shared-ownership properties, rent-to-buy products or affordable rents set at 80 per cent of market rate. Few if any homes for social rent, fixed at 30 per cent of market rate, are being built to replace the thousands being lost. The effect of this programme, which every council in London is implementing on their housing stock, has been described with a term that still causes anger and furious denials in those carrying it out, but which has been universally adopted by both residents and campaigners resisting it: social cleansing.

ASH was set up in March 2015 to offer an architectural alternative to this estate regeneration programme, one that addresses London’s need not only for low-cost housing to buy, but also for more – not less – homes for council and social rent. London’s housing crisis is a crisis of affordability, not of supply, with the numbers of unaffordable, uninhabited prime and sub-prime properties far outstripping demand. According to research by Savills real estate firm into housing provision in London between 2017 and 2021, 58 per cent of demand in London is for homes for sub-market rent and lower-mainstream properties priced below £450 per square foot (the conversion to Euros is currently 1.16); yet only a quarter of the approximately 38,500 properties set to be built over the next five years will be available at this price. Instead, in 2017 builders started work on 1,900 properties in London priced at more than £1,500 per square foot – over three times as much. As of January this year, only 900 of these prime properties had been sold; and there were an additional 14,000 unsold lower-prime properties on the market for between £1,000-£1,500 per square foot. And despite a demand for 20,000 homes for social rent in London, not a single such home was built in the capital in the year up to October 2017, and a mere 5,700 are planned to replace the tens of thousands that are being demolished. It stands to reason that during such a crisis of affordability, which is pushing increasing numbers of Londoners into housing poverty and homelessness, the last thing we should be doing is demolishing the city’s dwindling number of council estates.

Nor is it necessary to do so. Over the past three years ASH has designed alternatives to demolition up to feasibility study not only for Central Hill – the subject of our case study – but also for the West Kensington and Gibbs Green estates (top left), and as options for Knight’s Walk (top right), the Northwold estate (bottom left) and the Patmore estate (bottom right). Through these design proposals, ASH has demonstrated that, without demolishing a single home or evicting a single resident, we can increase the housing capacity on these estates by between 40 and 50 per cent. In addition, by selling and renting around half of the new builds on London’s private market, we can raise the funds necessary to carry out the long-neglected maintenance and refurbishment of the existing estate; with the other half of the new builds supplying the homes for council and social rent for which there is so great a demand. Not only that, but pricings of our proposals have consistently shown that the financial cost of the infill and refurbishment of these estates is a fraction of the cost of their demolition and redevelopment.

Our aim in drawing up these proposals has been twofold. On the one hand, we wanted to provide practical and financially viable options for the refurbishment and increased housing capacity of these estates to be used by residents in their campaigns to try and save their homes and communities. We call this model ‘Resistance by Design’. But we also wanted to demonstrate publicly and in detail that – far from being an economic necessity enforced by central government cuts to council budgets that preclude the maintenance of existing homes, or imposed by government restrictions on councils borrowing against their assets to build new council homes – the estate regeneration programme in its current form is a political choice, made in response to the enormous profits being made on London’s hugely lucrative housing market.

Increasing numbers of architectural practices are being drawn into this programme and the housing crisis it has done so much to create: not only as designers but as mediators between councils and the residents their designs will evict from their homes. In the three years that ASH has been in practice, the role of the architectural profession in this process has been one of quiet complicity, with an on-going refusal to look outside the parameters of the client brief or accept responsibility for its results. ASH believes this is an abnegation of the duties of the architect – duties that were no better performed than in the design of the post-war council estates that are being lost to the demolition programme, and which envisioned and provided a new model of community living actively opposed to the current conception of architecture as embodied capital.

2. The Central Hill Community

In April 2015, ASH was contacted by residents of Central Hill, a council estate in Crystal Palace, South London. A core group of around 40 residents had started the ‘Save Central Hill Community’ campaign that February, and were fighting to save their homes from demolition at the hands of Lambeth council, which had formally added the estate to its regeneration programme in December 2014. Central Hill is an extremely well-designed estate whose masterplan, drawn up by architect Rosemary Stjernstedt – a member of Lambeth’s Architects Department under the celebrated architect Ted Hollamby – is an exemplar of community living and estate planning. Built between 1966 and 1974 in response to Hollamby’s reservations about housing families in tower blocks, Central Hill’s low-rise, high-density blocks contain 476 maisonettes and flats that are home to an established community of over 1,200 residents, many of whom have lived there since the estate was completed.

One of the immediate hurdles we faced was that Lambeth council had prohibited residents from using the estate’s community hall except on council business, so there was nowhere for us to meet with them. Moreover, the residents who sat on the Residents Engagement Panel, which included Lambeth councillors, regeneration officers and independent resident advisors, were not given the means to convey the information to the residents they were supposed to be representing. Initially, therefore, we met in a back room of the local Gypsy Hill Tavern, where we held workshops with residents. These helped us get to know the estate and how it worked, as well as listen to residents concerns about the council’s consultation process. The workshops were complemented by resident-led tours, during which we mapped the estate and its uses, and by November ASH had drawn up a series of design proposals and possible initiatives.

From this process emerged a new model of consultation. While architectural practices typically come into estate regeneration with a fixed set of objectives supplied by the council for the demolition and rebuilding of the existing estate, and then use the consultation process to generate the reasons to justify this, ASH, in contrast, started by asking the residents about their needs and wishes, then used these to generate objectives and the way to bring this about. This is a process that moves from the inside to the outside – from the community to a genuine estate regeneration that works for the benefit and continuation of the existing community.

In contrast, PRP, the architectural practice that had been commissioned by Lambeth council to design the redevelopment options, began their consultation with the residents by posting on their Twitter account a photograph taken of the estate at night with the caption: ‘Would you walk down this alleyway!’ However, following ASH’s publicity campaign for Central Hill, in January 2016 the architectural critic, Rowan Moore, published an article, illustrated with photographs taken by us, in which he was critical of the council’s plans to demolish the estate. In response, Lambeth’s Cabinet Member for Housing retorted with a blog post illustrated with a photo of mould in a resident’s home, which he claimed as evidence that the estate had to be demolished. That same month the Prime Minister, David Cameron, enshrined this emotive narrative of ‘sink estates’ in the government’s Estate Regeneration National Strategy. To counter these negative representations of council estates – which are targeted at the communities and much as their homes – in February 2016 ASH published a series of photographs of Central Hill estate bathed in sunshine and filled with life. To expose the economic and political motivations behind estate demolition, we captioned these photographs with stereotypical statements made by the government, mayor, councils, developers, journalists and architects as part of the propaganda that is crucial to winning public acceptance for this programme.

Many of these photographs had been taken the previous June at Open Garden Estates, a London-wide annual event that ASH has organised for the past three years, and which has so far been hosted by 18 estates, including Central Hill, that are threatened with demolition. Open Garden Estates is an opportunity for residents to open up their estate’s green areas, communal spaces and private gardens to the public, and in doing so help change the widely held but inaccurate perception of council estates as ‘concrete jungles’. Walking tours for visitors organised by residents, and with maps made by ASH, show how well the estates are designed for community living, and increase awareness of the strong and mixed communities that live on them.

Above all, Open Garden Estates has been a chance for estate communities to meet fellow residents, make connections with other campaigns and co-ordinate their efforts to save their homes. In 2015 the Central Hill community held a barbeque and puppet show on the slopes of their playing grounds, and in 2016 residents exhibited ASH’s designs in a marquee. This allowed large numbers of people to hear about the campaign, with over 100 residents and members of the public attending, effectively circumventing the council’s closure of the community hall.

In February 2016, ASH presented our architectural proposals for the continuation and future of the Central Hill estate community at an exhibition and meeting held in the local church. This meeting also functioned as a consultation workshop, with residents and community members writing down their comments and opinions about the proposals, which were subsequently incorporated into our designs. One of these said: ‘This is the first time architects have taken a real interest in the existing qualities [of the estate]’. Attended by over 120 residents and members of the Crystal Palace community, the ASH proposals received overwhelming support, and continue to be part of the campaign to save the estate from demolition, having received over 700 signatures in support of our plans, and a further 2,400 against the demolition of the estate. A ballot of residents conducted by the Save Central Hill Community campaign has shown that 77 per cent of residents have voted against demolition and for the refurbishment of the estate.

3. The Alternative to Demolition

ASH’s proposals for Central Hill estate are designed to respect and continue the existing architecture, both in its design intentions and its social vision. Laid out along the north face of a tree-lined ridge, these include the democratic access of all residents both to the panoramic views of London to the north (that make it such a coveted location for developers), and the sunlight from the south; the well-proportioned interiors designed to an interlocking, stepped design; the numerous outdoor and communal spaces; the car-free places where children can play in safety; and the many green passages that run through the estate, linking it to Crystal Palace Park to the east and Norwood Park to the west. Far from demolishing the estate, ASH believes we should be exporting Central Hill as a model of council housing that can meet London’s current housing needs.

ASH’s design proposals were made with three objectives:

- The continuation and improvement of the existing estate, with an increase in the number of homes;

- The generation of the funds to pay for its refurbishment;

- The continued existence of the community for which it is home.

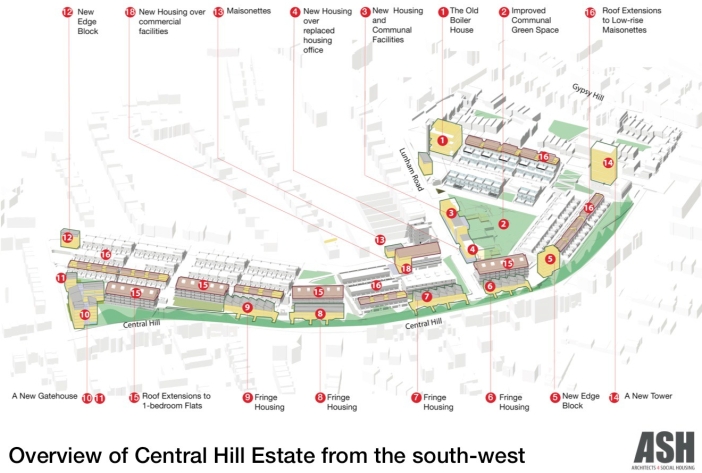

Through a combination of infill new builds (marked in yellow) on sites identified by residents, and roof extensions (marked in pink) to some of the existing blocks, ASH’s designs propose increasing the housing capacity of the estate by up to 242 homes. The sale or rent of a percentage of these on the private market will provide the funds to refurbish the existing 476 council homes, as well as increasing the number of homes for council rent. And, most importantly of all, these proposals keep the existing estate community together while also providing housing for newcomers. ASH has consulted Arups, the original engineers for Central Hill estate, on the viability of our designs for roof extensions, and they have approved our proposal. In addition to these fundamental aims, ASH’s designs also propose new community and commercial facilities for the estate, improve and expand its green and play areas, and, as part of our refurbishment strategy, address design and maintenance issues like refuse disposal, wheelchair access, poor lighting, uneven walkways, condensation and leaking roofs, all while maintaining and reaffirming the principles of the original design.

The new buildings ASH proposes for the estate fall into two main categories: infill and roof extensions. The proposed infill homes (Sites 1-14 and 18 in yellow) are situated on currently underused spaces around the estate that were identified to ASH by residents on walking workshops during the summer of 2015, and are generally located around the periphery of the estate, and creates new street edges. This design strategy addresses a common criticism of housing estates, and of Central Hill in particular: that they don’t have clearly defined edges or straightforward relationships to the traditional street patterns surrounding them. The infill architecture, accordingly, creates material and formal links between Central Hill estate and the neighbouring areas, both knitting it into the traditional street fabric and distinguishing clear entry points, while also reinforcing the design of the existing architecture and its distinct sense of place.

The proposed roof extensions (in pink) are limited to 1-storey extensions on the top of some of the 4-storey blocks (Site 15) and 1-2-storeys on the outer ring of low-rise housing (Site 16). The roof extensions, accordingly, are placed intermittently and with an undulating roof-line, to ensure a broken pattern of light penetrates the houses below, keeping the reduction of light and obstruction of views to a minimum.

Cities are not bland, homogeneous places but the site of cumulative memory and history. Rather than erasing this history, our proposal celebrates and supports the existing architecture and community while at the same time offering the potential for a significant number of new homes. The distinctive character of Crystal Palace is rooted in the diverse and eclectic range of architectural styles that have emerged as the area has evolved. From Victorian mansions to 1960s towers and the award-winning Central Hill estate itself, the on-going palimpsest of Central Hill is in keeping with the history of the area.

Our proposal retains and supports the local community and environment, which has matured and bonded over the past 40 years. The role of the existing community in the formulation and execution of the regeneration of Central Hill is a fundamental aspect of ASH’s proposal. The engagement of this long-standing community in the process has enhanced community cohesion, and a sense of ownership over these proposals has emerged. Rather than erasing its memory from the area like some forgotten mistake, these proposals will contribute to the on-going success of Central Hill, and have an impact on the effective use, maintenance and safety of its communal spaces.

ASH’s proposal for Site 1 is to retain the old boiler house chimneys, and establish a new entrance to the estate from the north while celebrating and remembering its past. The existing structure of the boiler house would be retained as far as is practical; with the lower, double-height space divided into two floors.

Two lifts would facilitate an additional 7 floors of wheelchair-accessible housing in this block, with the top floor set back to reduce its impact on the surroundings. Subject to resident and local neighbourhood consultation, the lower floor could be renovated for commercial use, or as a communal workshop – a proposal that came directly from the estate community.

ASH has undertaken a preliminary ‘right to light’ exercise that illustrates the new buildings will not have a significant impact on the closest adjacent buildings to be affected. We have illustrated the example of occupying the maximum footprint of the boiler house, generating a mix of wheelchair accessible homes.

The existing community facilities, which include a day-care centre, nursery and community hall, currently occupy a large area at the centre of Central Hill estate (Site 2). ASH proposes that these are demolished and re-provided at the edge of the estate along Lunham Road (Sites 3 and 4). This would increase the size of the green space and improve play facilities for the estate’s many children. In addition, we propose that the existing housing office be demolished and also be moved to Lunham Road, further freeing up green space for residents.

Above these new community facilities we propose building new housing with a total of 38 new flats of varying sizes. The deliberately fragmented character of our proposed new developments is a defining feature of the existing estate, which our designs seek to emulate. In addition, the discontinuous plan of the blocks mirrors the detached houses on the other side of Lunham Road. The heights of the proposed blocks are also variable, creating a punctured skyline when viewed from the estate, and ensuring that every resident retains their views of London across and between the new undulating roof-scape.

Central Hill is steep and, at the top, considerably higher than the access road onto the estate. In order to address the difficulty of disabled access into the estate at this point, we propose a new block that would incorporate a double lift core, enabling wheelchair and elderly accessibility not only into this block, but also into the rest of the estate below.

Access would be by foot directly off Central Hill (the main road) with parking below. The proposed 6-storey building is relatively small in plan and located on the edge of the estate. Nestled well within the existing trees like all the buildings along the Central Hill main road it wouldn’t affect access to light and existing views of surrounding properties, or views from and of London and the trees. Being predominantly adjacent to flank walls, it would have negligible impact on the existing neighbouring blocks on Central Hill estate itself.

For new infill housing along Central Hill road ASH proposes terraces of maisonettes elevated above the access road. These would retain the existing tree line, and views to and from Central London, while clearly reinforcing the edge of the estate.

Short walkways and ramps would connect the new buildings and the estate to the main road, both improving the permeability of the estate and providing improved access for elderly and disabled residents. Formally, the zinc saw-tooth profile of the proposed fringe housing roof-scape is intended to reference the architecture of the later Gipsy Hill section of the estate to the east, while maximising the light into the rest of the estate behind and providing a durable, low-maintenance roof.

At the south-west corner of the estate on the site of an existing hostel, ASH proposes the construction of a new 5-7-storey block of flats (Site 10), as well as a smaller block closer to the low-rise housing to the north (Site 11). These sites are immediately adjacent to wide roads, so the buildings would not have any detrimental impact on any of the existing neighbouring houses. In order to establish a sensitive relationship with their surroundings, the form and material of the new development could emulate those of the existing buildings. Roofs could either be pitched to correspond with the proposed roof extensions to the existing adjacent blocks, or turned into green roofs – or a combination of the two. We would also use materials and forms that create relationships between the old and the new; such as making use of white flint lime bricks of the existing buildings.

On site 12, assuming the existing parking space is required, ASH proposes a small 3-4 storey block of flats above the existing car park. Although it would not noticeably affect light on the surroundings, a taller building may be less appropriate in this location, so we have reduced the height of this block to minimise its impact on the neighbouring buildings.

The new gateway to the estate on site 10 is designed to ensure the minimal loss of trees and the creation of a communal courtyard garden for the flats, as well as individual back gardens for the ground-floor maisonettes. Two lifts would allow this whole block to be wheelchair accessible, with maisonettes on the ground floor would be accessed directly from the street, enabling an architectural transition from the urban space of the street to that of the estate. These new buildings would reinforce the boundaries of the estate and link it closer to the neighbouring streetscape.

ASH originally proposed a new tower on the site to the rear of the old Gipsy Hill police station. The front of the police station would remain as part of the existing streetscape with the new taller building built behind with an additional 20-25 new homes. This proposal has subsequently been omitted due to the fact the land is not owned by Lambeth council. However, we note this has not stopped the council from issuing compulsory purchase orders on other privately-owned property in other estate regeneration schemes; so this is a reflection of the council’s lack of will, rather than an unsurpassable obstacle to building the many new homes that could be accommodated on this site. Indeed, under new government guidelines on disused sites, councils have a duty to identify and make available all such land for redevelopment.

Here one additional floor is proposed on top of some of the existing 4-storey blocks. Access to this additional floor would be by extending the already existing staircases and, where necessary, adding lifts to the side of the blocks. Materially, these extensions would be made of prefabricated timber, or similar lightweight construction, and craned onto site. This construction method is not only quick, but also minimises the amount of dust and noise for the existing residents, keeping disruption to a minimum.

The durable zinc pitched roofs we propose would allow daylight to pass through to the flats to the north, as well as requiring lower maintenance than the existing flat roofs. Structurally, the existing 3-4 storey blocks have been surveyed by Arups, the engineers of the original estate, who declared them capable of accommodating at least one additional storey.

ASH proposes the addition of between 1 and 2 floors on top of some of the existing homes around the edges of the estate, but only where this doesn’t affect existing views within the estate. This housing would again be light-weight and prefabricated. The design of these new homes and the use of pitched zinc roofs, means that the additional housing would not present a single monolithic block, but would undulate, minimising the impact on the light of the existing homes below.

Access to these new prefabricated flats would vary for each block, but typically it would be via a new stairwell located either centrally within the ‘ways’ or to one side. The individual flats would be accessed via a deck and overlooking into the gardens below would be moderated by the use of deep built-in plant boxes where necessary. Roof gardens would be provided for each new flat, which would formally break up the mass of the new additions. The new roof extensions on top of the existing low-rise blocks would also increase the number of ‘eyes on the street’ and improve the self-regulation of the pedestrian ways that traverse the site.

Dependent on structural capacity, there is also an option to add 2-storey homes to the existing flats. As with the single-storey option, the low-rise extensions would be punctuated by roof gardens to break up the massing, and as before, views from these gardens and homes could be moderated by the use of deep plant boxes. The designs of these new roof extensions would need to carefully relate to the homes below through sensitive use of proportion, fenestration and material.

One of the criticisms of Central Hill estate made by Lambeth council is the steepness of the site and the difficulties of navigating the pedestrian routes. In reality, the rich relationship of the architecture to the steep site is a unique feature of the estate, and should be dealt with sensitively and celebrated, not obliterated.

The lighting on the estate is currently poor, and well-designed up-lighting would eliminate glare, and address concerns people may have about walking around the estate at night. Another proposal made by residents is the possibility of reducing the heights of the garden gates and bin stores, enabling greater visibility from kitchens through the front gardens onto the internal streets. Trellises could be installed for growing plants, but would still allow for a more open relationship to the pedestrian ways.

Following conversations with residents of Central Hill estate, ASH is aware there are problems with the existing homes, such as mould and condensation. These are common problems, however, typically caused by badly designed and poorly fitted windows being installed in place of the original ones, and are very easily remedied by well-designed and careful refurbishment. This problem is neither peculiar to council estates nor a justification for their demolition, as has been suggested by Lambeth council.

The very simple solutions are improved ventilation strategies, better double-glazing and local insulation to cold bridges. The tops of walls need to be adequately protected from water ingress, and the glazing to the balconies needs to be replaced. Roofs and floors to balconies will also need to be re-made throughout. The key to quality construction is to ensure good workmanship and warranties to the work.

In accordance with our proposal for roof extensions, all the roofs on the outer ring of blocks would be replaced and green roofs installed across the remaining refurbished, low-rise, flat roofs. Photo-voltaic panels, solar heating and hot water could additionally be installed, where appropriate, on all new pitched roofs, and the possibility for sustainable energy resources should be investigated further.

ASH has also identified opportunities to extend the existing maisonettes onto the balconies, increasing the available floor space of the existing homes by around 20 square metres. The capacity of the existing estate architecture to accommodate this kind of increase in additional floor space illustrates the flexibility of the existing structure and layout.

ASH has worked closely with Central Hill residents to come up with proposals for improvements to the landscape of the estate including new designs for balconies and patios, the introduction of a marketplace in the main square, vegetable gardens and playground improvements, as well as proposals for the reuse of the sculptural recycling castles, some of which the residents are already putting in motion.

We also propose reinstating the wonderful planting which was a key design element of the original estate. As part of the managed decline of the estate, this is currently being destroyed by Lambeth council, who have dug up trees and bushes without consultation, removed plant boxes and roof gardens and torn down ivy-grown trellises.

5. The Costs of Demolition

It was important for us that ASH’s proposals were not merely defensive and reactive, and that we also challenged the suppositions on which Lambeth’s estate regeneration programme had been launched in October 2012. In August 2016, therefore, we published an article that counted the costs of demolishing Central Hill estate:

- Socially, to the current residents of the estate;

- Financially, to both residents and the council;

- Environmentally, to the wider Crystal Palace community.

Lambeth council proposes developing the new housing complex under a Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) which they have called ‘Homes for Lambeth’. This is a holding company in which the council will hold 100 per cent of the shares, but which is a private company that will contract out development, construction and management to other private companies. Residents fear the privatisation of the proposed new development will not only lead to the dispersal of the Central Hill community, but will replicate the same unaccountability in management and cost-cutting in maintenance that led to the fire in Grenfell Tower last year that killed over 70 people.

What is certain is that this decision has condemned tenants not only to the loss of their secure tenancies, but also to rent and service charge increases sufficient to exclude many – if not all of them – from exercising their ‘right to return’ to the new development. Meanwhile the compensation the council has offered to leaseholders for their demolished homes is around a quarter of what is required to buy their replacements under a shared ownership scheme in which they would have no more security than an assured tenancy. Under the business plan for Homes for Lambeth, the management of what is currently a council estate but will become a housing association is contractually obliged to extract the greatest profit from a new clientele of property investors, buy-to-let landlords and home owners. The social cost of the so-called ‘regeneration’ of Central Hill estate, therefore, as on so many other similar schemes, will be the break-up of the long-established community and the dispersal of its members across the borough and beyond – in some cases out of London altogether.

So what of the financial cost of demolition, which amongst its criteria Lambeth council specifies must be ‘good value for money’? Savills real estate firm, which is advising Lambeth council on setting up Homes for Lambeth, have estimated the cost of demolishing council homes at £50,000 per unit. This means that demolishing the 456 council homes they have targeted on Central Hill estate will cost the council £22.8 million. And at an average construction cost of between £225,000 and 240,000 per property, rebuilding the 456 existing homes alone will cost from £100-110 million. Add on design fees and management costs, together with decanting, land acquisition and compensation costs, and that figure is likely to be closer to £295,000 per new build property. This means a total cost to the council of over £157 million before a single additional property has been built.

In contrast to this huge sum, Robert Martell and Partners, an independent firm of chartered surveyors, has undertaken a pricing of ASH’s design proposals, and has costed the 242 new builds we have proposed at £45 million. Lambeth council’s own surveyor has estimated the cost of refurbishing the estate at £18.5 million – around £40,000 per home, £10,000 less than the cost of demolishing them. Together with external works and services, professional fees and contingency funds, the ASH scheme has been costed at a total of £77.5 million. That’s less than half the financial cost of merely demolishing and rebuilding the existing homes in every one of the redevelopment schemes proposed by the council.

As for the environmental cost of demolition, at our request engineers Model Environments have produced an ‘Embodied Carbon Estimation for Central Hill Estate’, in which they concluded:

‘A conservative estimate for the embodied carbon of Central Hill estate would be around 7000 tonnes of CO2e. These are similar emissions to those from heating 600 detached homes for a year using electric heating. Annual domestic emissions per capita in Lambeth are 1.8 tonnes in 2012. Therefore, the emissions associated with the demolition of Central Hill estate equate to the annual emissions of over 4,000 Lambeth residents.’

As Model Environments emphasise, this is a conservative estimate of the effects of demolition, and says nothing about the carbon emissions, dust and particulates from the redevelopment, or from the increased traffic on Crystal Palace’s already overloaded roads from the addition of well over a thousand new residents. In July 2014, at a Housing Committee meeting convened by the London Assembly, Chris Jofeh, the Director of Arups, testified that it could take 30 years before gaining any environmental benefit from the demolition of council estates and their replacement with more energy-efficient buildings.

5. Viability, Confidentiality & Transparency

So what went wrong? Why – given a design proposal that has been hailed by other architects, planners, engineers, quantity surveyors, environmentalists, academics, housing campaigners and the residents themselves, even by politicians, as the preferable, most sustainable, most financially prudent, most environmentally friendly, most socially just option for the future of Central Hill estate – why was the ASH proposal rejected out of hand by Lambeth council?

Well, for a start, not a single one of Lambeth’s 63 councillors attended the presentation of our proposals in February 2016, not one even of the ward councillors for Crystal Palace, which included the Cabinet Member for Housing. This wasn’t surprising, as the council’s comments on ASH, even before they had seen our proposals, had been unremittingly negative. It wasn’t until that May that we were finally able to organise a second presentation, this time to the Central Hill estate Residents Engagement Panel – at which, once again, not a single Lambeth councillor was present. That didn’t stop Lambeth council, the following month, from releasing a brief report declaring our proposals to be ‘financially unviable’. They backed up this claim with a Draft Feasibility Report produced by chartered surveyors Airey Miller. Our inspection of this report, however, revealed it not only to be based on miscalculated figures, inaccurate assessments, incompatible assumptions, false claims and deliberate misunderstandings of ASH’s proposal, but that the figures on which its financial feasibility had been dismissed had been redacted across no less than 23 pages.

The first thing we did in response, therefore, was to publish a point-by-point refutation of the inaccuracies in the feasibility report on which Lambeth council’s dismissal of our proposal was based. We never received any response to this. Nor were we invited to the subsequent meetings at which the council discussed and dismissed our proposals with the Resident Engagement Panel. So we also initiated a long struggle, which continues to this day, to get Lambeth council to make the redacted financial information public. Despite our appeals to both the Greater London Authority and the Information Commissioner’s Office, Lambeth council continues to refuse to supply us with this information. Their argument for doing so is that Homes for Lambeth, the company under which Central Hill estate will be redeveloped, marketed and managed by private development partners and financiers, is a commercial project. Therefore, despite the fact that their regeneration scheme will lead to the demolition of 456 council homes and the privatisation of a council estate of over 1,200 people, not only the financial information about Homes for Lambeth, but also the redacted figures in the feasibility study of ASH’s proposal, is judged by them to be ‘commercially confidential’.

In the middle of this struggle for information that should clearly be made public, in March 2017, some 8 months after we made our Freedom of Information request and 10 months since we had presented our proposals to the Resident Engagement Panel, Lambeth Cabinet announced its decision to demolish Central Hill estate. Objections to the decision by residents and campaigners were dismissed out of hand and for the last time at the overview and scrutiny hearing the following May. Finally, therefore, in October 2017, ASH published a long report on the rejection of our Freedom of Information request, and our attempts to pull back the cloak of commercial confidentiality behind which our proposal for the refurbishment, infill and maintenance of Central Hill estate has been dismissed by Lambeth council without either verifiable justification or recourse to public scrutiny.

6. The Housing Crisis

There is nothing in the Mayor’s London Plan or the Greater London Authority’s Good Practice Guide to Estate Regeneration, in the Government’s Estate Regeneration National Strategy, the Housing and Planning Act 2016 or in the housing manifestos of the Conservative, Labour or Liberal Democrat parties, that will do anything to stop other estates being demolished on the basis of the same unverifiable claims, through the same or a similar process, and with the same results. We already have examples of what these will be in such notorious ‘regenerations’ as those implemented against the more than 5,000 residents of the Ferrier estate, where over 1,700 homes for council rent were lost; and the 3,000 residents of the Heygate estate, where nearly 1,000 homes for council rent were lost:

- The demolition of London’s council and social housing stock in the middle of a crisis of housing affordability;

- The social cleansing of the existing communities from their homes;

- The replacement of council-owned housing stock with properties for capital investment by offshore companies, buy-to-let landlords and home ownership unaffordable either to the existing residents or to most Londoners;

- The privatisation of public land, the new developments built on them and their management, resulting in greater unaccountability to residents;

- The driving up of London house prices to some of the most expensive in the world;

- And the increase in the number of Londoners being pushed into an unregulated private rental market that is causing increased housing poverty and homelessness.

London house prices have risen by 86 per cent since 2009, and at an average asking price of over £600,000 now cost more than seventeen times the average London salary of £35,000. In Inner London that price rises to an average of £970,000. Home ownership in the UK, which peaked at 71 per cent in 2003, has been declining ever since and now stands at 63 per cent; while in London only 47 per cent of residents have a mortgage or own their own home.

As a consequence, rents on London’s private rental market, in which 30 per cent of households in London now find their home, have risen to an average of £1,532 per month in January 2018, more than twice the national average. The total rent paid by UK tenants last year rose to £51.6 billion, more than double the £22.6 billion paid they paid in 2007. Millennials aged between 22 and 40 paid £30.2 billion of that rent, which is more than three times the £9.7 billion the same age bracket spent in 2007. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation has predicted that over the next quarter of a century rents will rise at twice the rate of incomes, and renters will be twice as likely to live in poverty.

As a result of this huge escalation in the cost of housing, at the end of last year the charity Shelter estimated that there are now 307,000 people in Britain who are homeless – meaning accommodated in temporary housing, living in bed & breakfasts and homeless hostels or sleeping rough. That’s one in every 208 of the UK population. In London, where 165,000 people are homeless, that figure rises to 1 in every 59. These numbers, however, don’t include the hidden homeless, with an estimated 1 in 5 people under the age of 25 having slept on someone’s couch or floor over the past year, a quarter of a million of them in London.

This trend is predicted to increase, with Shelter warning that more than a million UK households are at risk of becoming homeless by 2020. Under Shelter’s Living Home Standard, across the whole of Britain the homes of 41 per cent of semi-skilled and unskilled workers, and 31 per cent of skilled workers, fail to meet the criterion for affordability – defined as no more than third of income spent on accommodation; while in London that figure rises to 56 per cent of all homes.

If we are to come up with real solutions to London’s housing crisis it is vital that we change the current programme of estate regeneration. Existing legislation has been written to accommodate the demands of property speculators for greater profits, not the needs of Londoners for housing they can afford. The solutions to this crisis proposed by all three major political parties are all in agreement with each other that building more properties will reduce prices. But while the law of supply and demand describes a capitalist myth of competitive markets responding to human needs, London’s financialised housing market, flooded by global capital, is driven by the profit margins of investors demanding high returns on secure investments.

More than 100,000 UK land titles are registered to anonymous companies in British overseas territories such as Panama or the Virgin Islands, and offshore companies have acquired at least £170 billion worth of properties in the 10 years between 2005 and 2014. Transparency International has been unable to identify the real owners of more than half of the 44,000 land titles registered to overseas companies, but 9 out of 10 of the properties were bought through tax havens. An extraordinary 30 per cent of properties sold in London in 2017 were bought by overseas investors. At the high end of the market that increased to over 50 per cent. Building more such properties for capital investment, buy-to-let landlords and home ownership has pushed – and will continue to push – house and rental prices up. And yet that is precisely what the councils, housing associations, property developers, estate agents, architects and builders given the task of solving the housing crisis are doing.

In particular, the building companies to whom the government has handed over the responsibility for solving the housing crisis are making unprecedented profits from spiralling house prices and an unregulated private rental market. The pre-tax profits of the four largest builders in the UK – Persimmon Homes, Taylor Wimpey, Barratt Homes and the Berkeley Group – rose from just under £419 million in 2011 to over £2.6 billion in 2016. That’s a more than six-fold increase in just five years. And yet between them they built just 29,800 new properties in 2016. Anyone who understands that market value is created by demand rather than supply will not be surprised to hear that the same builders are sitting on land with planning permission to build nearly 284,000 homes. Indeed, there is an inverse relationship between the number of properties built and the rising price of those properties. Land, not materials or labour, determines the value of property, and the less there is of it available for building the more that land costs, and the higher the price of the properties built on it.

We might deplore this pursuit of profit at the expense of housing provision as immoral – and other such liberal critiques; but private companies have obligations only to their shareholders, not to the needs of their customers. If we want to solve the housing crisis we need to start by changing UK legislation and policy at central and local government level so that the nation’s housing supply is brought under the direction of the needs of its citizens, not the profit motives of developers, investors and speculators. Until we do, far from solving the housing crisis, the programme of estate regeneration will continue to reproduce and expand that crisis across the UK.

In place of this self-perpetuating cycle of capital accumulation, ASH offers a model of estate regeneration that we have developed in our design proposals for the infill and refurbishment of six London housing estates, and which addresses some of the worst effects of this crisis: by building the homes Londoners present and future can afford to rent or buy; by increasing the supply of homes for council and social rent Londoners need; by generating the funds to refurbish the existing homes; and, above all, by ensuring long-standing communities and their support networks remain together. Ideologically opposed to the property speculation, land-banking, privatisation of public land and assets and social cleansing that has made London’s housing market a subject for investigation by the United Nations into abuse of human rights, we believe the ASH model of estate regeneration provides the most socially, financially and environmentally sustainable solution to the housing needs of all Londoners. In the words of Richard Rogers, the one-time socialist architect turned designer of corporate headquarters and investments for property magnates: ‘Architektur ist immer politisch’.

Geraldine Dening and Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the vast majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work, you can make a donation through PayPal:

One thought on “Central Hill: A Case Study in Estate Regeneration. ASH Presentation to the Department of Architecture, Braunschweig University of Technology”