1. False Gods: Demolishing the Past

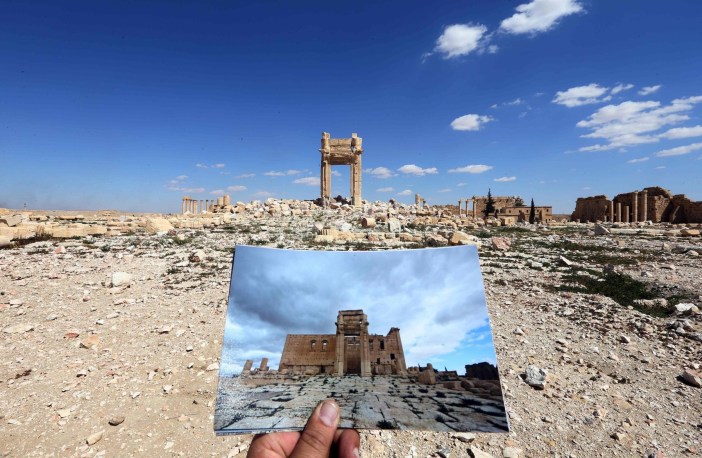

When Islamic State captured the ancient city of Palmyra in May 2015, antiquarians across the world held their breath. Dating back to the early Second Millenium BC, the city is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with a repository of temples, tombs and statues that its latest conquerors had demolished in numerous other sites during its conquest of Syria and Iraq. Sure enough, that month the Lion of al-Lāt, a statue from the First Century AD adorning the temple of the pre-Islamic goddess, was demolished. In August the Temples of Bel and Baalshamin followed suit; and in September three tower tombs, including the Tower of Elahbel, were similarly destroyed. The Western World, which had looked on with indifference as Syria was torn apart by civil war and its people butchered or scattered to the four winds, reacted in horror to this desecration of the ‘Cradle of Western Civilisation’. Denounced as cultural vandals by Western media, Islamic State justified their iconoclasm through Salafism, the conservative reform movement within Sunni Islam that places great importance on establishing monotheism and destroying polytheism. To reinforce their message, among the hundreds of soldiers and government servants they executed, Islamic State also beheaded an 81 year-old archaeologist, Khaled al-Asaad, who had worked for over 40 years as head of antiquities in Palmyra, and hung his body on a column in the main square. This, if further evidence were needed of their atrocities, was the final proof of the barbarism of Islamic State, which British Muslims queued up to denounce as contrary to the teachings of Islam.

The Palmyrenes who built these monuments in the First and Second Centuries AD, when they were subjects of the Roman Empire, were a mix of Amorites, Arameans, and Arabs. They spoke a dialect of Aramaic, employed Ancient Greek for commerce and diplomacy, and – until their conversion to Christianity in the Fourth Century – worshiped a mix of local, Mesopotamian and Arab deities. The statues they made of their gods, therefore, were not conceived as sculptures for aesthetic appreciation, but as embodiments of the deities appealed to in their religious ceremonies. In contrast, the modern conception of sculpture was born during the Southern Renaissance, when Donatello, Michelangelo and later Bellini sought to equal the naturalism of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture, carving the human form from marble or casting it in bronze. But the statues they aspired to surpass in formal mastery were originally painted with flesh tones and adorned with robes and jewellery, with precious stones placed in the sockets of their eyes to make them as life-like as possible. It was only when their painted flesh had worn away, the robes and jewelry had long since been stolen, and the precious stones had been prized from their eye sockets, that their use value as ritual objects was supplanted by their aesthetic value as works of art. If the ideologues of Islamic State saw a devil in the Lion of al-Lāt and a place of pagan worship in the Temple of Bel, they at least regarded them as they had been intended by their makers: not as objects for aesthetic contemplation in the museums of Western capitalism, but as idolatrous embodiments of false gods. Whatever ritual value they retained from the religious practices of Second Century Palmyra, their destruction by Islamic State paid them a more accurate hommage than to be buried alive in the profane halls of the British Museum and its equivalents in every Western city.

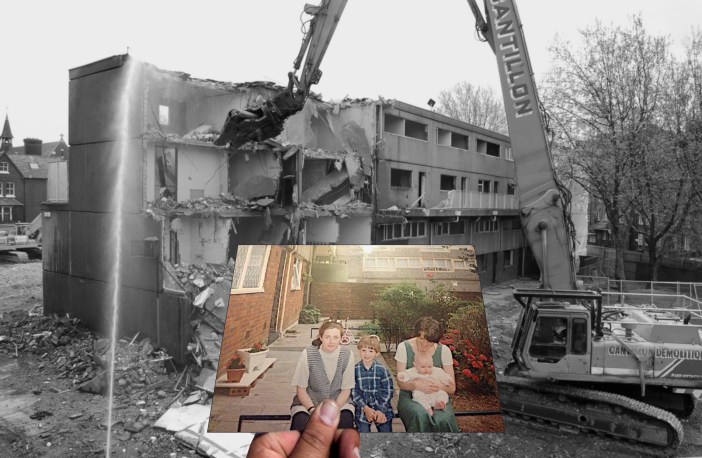

This might seem an odd way to start an article about the demolition of England’s council estates, which is what this is about; but I want to draw a comparison – first, and most obviously, between the mass demolition of council housing in England following the policy of central government, municipal and local authorities alike, and the parallel demolition of pre-Islamic monuments and buildings in Syria and Iraq by Islamic State; but also between the role played by Western aesthetics in, on the one hand, condemning the vandalism of Islamic State in the middle of a civil war, and, on the other, justifying the demolition of what’s left of our council housing in the middle of a crisis of housing affordability. For in preparing the ground, quite literally, for the assault on council housing and the working-class communities it houses, aesthetic judgements have been wheeled out with the irresistible logic and scaremongering of Tony Blair’s Iraq Dossier, playing on the public’s fears, reinforcing stereotypes, and appealing to commonly held aesthetic judgements about how other people should live. And as happened with the invasion of Iraq, the taste of the people, and the disgust and fear by which those tastes have been nurtured and shaped by the mass media, continue to play a deciding role in the decisions to destroy the legacy of council housing in this country.

To take only the most public example, which has been echoed across local authorities under Conservative, Labour and Liberal Democrat councils, Conservative Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision, in January 2016, to demolish 100 so-called ‘sink estates’ was justified not by facts and figures, but by stereotypes about the supposed failure of the post-war, modernist architecture that took millions of working-class households out of Victorian slums. Monuments to the failure of socialism, breeding grounds for criminal behaviour, structural causes of rioting, homes to troubled families, gifts to gangs and drug dealers, poverty traps for those left behind by capitalism’s inexorable triumph: each one of these stereotypes was offered with the smug certainty of referencing a hundred reality TV shows, tabloid headlines, BBC news reports, politician’s interviews, and all the other products of the propaganda industry that works overtime to shape the electorate’s view of the world. None were backed up with anything like credible research; all relied on aesthetic responses triggered by phrases like ‘sink estates’, ‘bleak, high-rise buildings’, ‘concrete slabs dropped from on high’, ‘brutal high-rise towers and dark alleyways’. As a result, the homes of 3.9 million British households have ultimately been condemned on nothing more than a taste in architecture.

2. Architecture and Social Cleansing: Robin Hood Gardens

In direct opposition to Islamic State’s rigorously literal appreciation of the use-value of the ancient statues and temples they demolished, the German literary theorist, Walter Benjamin, argued in 1936 that the new and defining characteristic of twentieth-century politics was its aestheticisation. In point of fact, Benjamin identified such aestheticisation as the logical outcome of fascism; but history has shown him to have been more prophetic than he could have known, with politics since the Second World War inseparable from the power of the spectacle to mobilise the masses to political inertia. By then Lenin had already defined fascism as ‘capitalism in decay’, and the Nuremberg rallies now look like a crude prototype of the reality TV show of US politics, with the tragedy of Mussolini and Hitler farcically repeated in the bankrupt gameshow host Trump and, most recently, our own bumbling blond bombshell. And just as fascism dressed its murderous ideology up in saccharine images of fallen war heroes, statues of neo-classical nudes wielding agricultural tools, and idealised depictions of a pre-industrial German countryside, so too the Neo-liberal revolution that has determined and defined the economics of capitalism over the past forty years has been indoctrinated in its willing subjects through the aestheticisation of our political life. Rather than constituting a discrete field of ideology alongside and parallel to our legal, political and educational superstructures, aesthetics has permeated all of these as the primary medium through which the ideology of neo-liberal capitalism is produced, implemented and consumed.

As an example of which, in 2008, following the decision by Tower Hamlets council to demolish Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar, East London, a campaign to have the estate listed as a building of unique historical value was launched by the Twentieth-Century Society. This garnered the support of such high-profile architects as Richard Rogers and Zaha Hadid, the later of whom described the estate as her favourite building in London. Designed in the late 1960s by Alison and Peter Smithson, Robin Hood Gardens was a pioneer in translating the modernist principals of Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles into a UK context. Despite this, and overriding the recommendation of its own advice committee, English Heritage rejected the proposal. But just to make sure, the following year the then Labour Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport, Andy Burnham, gave the building a certificate of immunity that precluded Robin Hood Gardens from being reconsidered for listing for at least five years. This gave the Labour council the time to demolish the estate and award the redevelopment contract to Swan Housing Association, which it did in 2010. Undeterred, in 2015 a second application to have the estate listed was launched, again with the support of numerous architects; but, once again, the application was rejected by English Heritage, and two years later, in August 2017, the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens began.

I was talking recently with a Croatian friend who is studying for a Masters Degree in ‘The Baroque City’ at the University of British Columbia. I was telling him how many contemporary British architects, such as Zaha Hadid and Herzog & de Meuron, consciously trace their work back to the architecture of Russian Constructivism, but have retained only its stylistic forms, having emptied them of their social and political dimension. I said that a similar thing is happening with the recent trend among middle-class property buyers for Brutalist architecture, two examples of which being the gentrification of London’s Brunswick Centre and Sheffield’s Park Hill estate. This trend has perhaps been most publicly expressed, however, in the privatisation and marketing of Balfron Tower in Poplar, where the social function of the Brownfield estate to which it belongs has been erased as cleanly as the former council tenants and replaced with a purely formalist (‘retro’) appreciation of brutalist forms, surfaces, textures and materials. In response, my friend reminded me that in the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia they didn’t call this architecture ‘brutalism’: they called it ‘socialist realism’ [socrealizam]’, as it was the social dimension of the architecture in housing large portions of the population to a high standard that mattered to the architects of socialism. Under capitalism, in contrast, the culture industry, including the architectural profession, always works to de-politicise, de-contextualise and ultimately to trivialise art and architecture through purely formalist aesthetic criteria that serve a more or less explicit political end. Through the dissemination of this politicised aesthetics in the media, entertainment and culture industries, and its implementation through our legal, civic and political institutions, the post-war council estates that took millions of Britons out of housing poverty, overcrowding, a lack of adequate sanitation and exploitation by private landlords are now judged – and ultimately condemned to demolition – on whether they appeal to the tastes of the agents of Neo-liberal orthodoxy.

Not once, accordingly, in the two campaigns to save Robin Hood Gardens, was mention made of what its demolition would mean for the residents living in the estate’s 213 homes. Instead, the debate, which was widely reported in the architectural press, hinged on the measure of its ‘architectural quality’. In the purely formalist discourse of capitalist architecture, this meant its aesthetic value stripped of the social function the estate served as home for more than 600 residents. In the words of Patrik Schumacher, one of the leading ideologues of Neo-liberal architecture, this aesthetic value constitutes what he believes should be the ‘unique and exclusive concern’ of architects. In obedience to which, in May 2018, the facade of a 3-storey section removed from the demolished east-block of Robin Hood Gardens was exhibited at the Venice Architecture Biennale. And in a final twist of the palette knife, this slice of the estate is destined to be put on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, presumably as a memorial to how working-class Londoners used to live before they were socially cleansed from the capital. Where the residents who lived behind them ended up will not, however, be part of the display, their very existence being judged extrinsic to the architecture that once housed them.

3. A Human Scale: The Aylesbury Estate

When David Cameron announced his decision to demolish 100 so-called sink estates in 2016 he was following in the footsteps of his political model and fellow ideologue of Neo-liberalism, Labour Prime Minister Tony Blair. Immediately after his landslide election victory in 1997, Blair made the – at the time – curious decision to deliver his inaugural speech on the Aylesbury estate in Camberwell, South London. Having announced his plans to ‘incentivise’ the ‘left behind’ with new welfare-to-work legislation that imposed sanctions on anyone who didn’t get on New Labour’s treadmill – policies that would be revived with interest by Cameron – Blair went on to launch the estate regeneration programme that in the more than two decades since has demolished, is in the process of demolishing, or is threatening to demolish, socially cleanse or privatise around 250 housing estates in London alone, over 195 of them in Labour-run boroughs, with the resulting loss of homes for council and social rent.

Nineteen years later, in 2016, the Public Inquiry called by leaseholders on the Aylesbury estate into the compulsory purchase orders issued on their homes issued by Southwark Labour council was one of the more demoralising spectacles to come out of this programme. On the one hand was a table of lawyers, Francis Taylor Building chambers, employed by Southwark council and paid with the rents of council residents to justify their plans to demolish the Aylesbury estate and hand over its redevelopment to the newly merged Notting Hill Genesis housing association. On the other were the leaseholders, members of the 35% Campaign, and a lawyer who’d had only a few days to familiarise himself with the hundreds of documents and thousands of pages after the previous lawyer had backed out at the last minute. Between them was an official who, to judge by her conduct of the inquiry, lived in the same Georgian townhouses as Southwark council’s Members of Cabinet, and drank cocktails in the same club as the lawyers. The residents didn’t have a chance.

I won’t recall here the relentless attempts of the head of Southwark council’s legal team, Melissa Murphy, to discredit the statements that had been given in support of the Aylesbury estate and against its demolition by the numerous academics, architects, engineers and housing professionals who had been called by the leaseholders. Between an earnest academic trying to extol the social benefits of council housing and a flint-eyed lawyer looking for chinks in a witness statement there was only ever going to be one winner; but one line of attack caught my attention. I believe Ben Campkin, the author of Remaking London: Decline and Regeneration in Urban Culture, was in the witness box when he was asked whether he thought the Aylesbury estate was built on a ‘human scale’. To give context to her statement, Ms. Murphy displayed several photographs of the Aylesbury estate – not when it was first built, of course, but in its current state after decades of managed decline by the council paid by residents’ service charges to maintain it. In particular, she attempted to draw contrasts that were not in their favour between the 14-storey, reinforced-concrete, modernist housing blocks that are the largest buildings on the Aylesbury estate and the 3-storey, timber and brick, Victorian terraced housing that predominantly lines the Walworth Road to the west. The point was obvious: how could the former be said to be on a human scale when so much of London, and indeed the UK, has lived in the latter for the past hundred years and more?

It’s a common and often-used argument, which draws on long ingrained and recently revived perceptions – or more accurately suspicions – that modernism is fundamentally an un-English and unwanted import from the continent, inappropriate to the climate of Britain, imposed on the British people by the vanity of European-influenced architects with at best visions of grandeur, and at worst intentions of socially engineering a socialist utopia that history has shown to lead straight to the gulag. But behind this reactionary rhetoric of Little England and Red-baiting there lies a far more powerful and – to use a Marxist vocabulary – economically determinate force which, far from being based in a conservative vision of terraced housing and Victorian streets, is at the forefront of capitalist economics and politics.

Under the religious fundamentalism of Neo-liberal capitalism, the human is now exclusively defined as individual, without class distinction (or as David Cameron, in another repetition of Tony Blair, declared ‘We’re all middle class now’), and property-owning; and that property is the repository and representation of the accumulated capital – or expendable wealth – of the individual. Under socialism, in contrast, and more generally its architectural realisation in modernism, the human was collective, and housing a means of eradicating at least the symbols of class distinctions, with the home allocated according to the needs of the household (and specifically its size), rather than the individual’s financial means of consumption.

When the lawyers, employed at great expense by Southwark council and with the funds collected from its constituents, argued that the Aylesbury estate on which around 7,500 of those constituents lived was ‘not on a human scale’, they were drawing on assumptions about the definition of the human under Neo-liberal capitalism every bit as ideological and fundamentalist – if not quite as violent – as the religious ideology of Islamic State. What was presented as an argument about architecture was, in effect, a religious declaration about who was and wasn’t human. Indeed, the decision of Southwark council to issue compulsory purchase orders against the homes of the Aylesbury estate leaseholders was initially blocked by the Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, who at that time was Sajid Javid, on the grounds that it violated their human rights (Article 8: ‘The right to respect for someone’s home’ and Protocol 1: ‘The peaceful enjoyment of their possessions’). But this rare upholding of a far from socialist definition of the human was quickly overcome by Southwark council offering leaseholders slightly more financial compensation for their demolished homes, thereby re-enshrining human rights within its capitalist equation with property rights, and the human with the consumer.

Dr. Campkin thought he had been called to the Public Inquiry to give his professional judgement about whether the Aylesbury estate that was home to 7,500 people should be demolished or refurbished. Instead, he was being asked to give an opinion about what was and wasn’t human in the pitiless eyes of capitalism. He blinked, and said he didn’t understand the question. But it’s a question that is being increasingly asked today, about who does and doesn’t have the right to live somewhere, not just in London but in the UK, in Europe, in the West. But the question is being framed not by our declared allegiance to supposedly universal human rights, but by aesthetic judgements, by consumer power, by the tastes of the ruling class. To have human rights under capitalism you have to look like a human with capital; you have to behave like a human who accumulates capital; and – it turns out – you have to smell like one.

4. The Smell of an Anarchist: Aesthetics and Politics

Five years ago, when we first founded Architects for Social Housing, and various anarchist groups were occupying council estates threatened with demolition, we had a policy of holding our meetings in these occupations. These included the Loughborough Park estate, the Aylesbury estate, the Sweets Way estate, and the Elephant and Castle pub. And I remember the smell of the anarchist squatters. I’m not much of a washer myself, but initially I was slightly repelled by their body odour, which reminded me of my own after a week of writing when I haven’t left the flat and confined my ablutions to a morning scrub in a basin. However, my admiration for what these anarchists were doing changed my reaction to their smell from mild repulsion to something approaching attraction. And – as if I were learning to appreciate a mouldy French cheese of acquired taste – I began to differentiate the smell of an anarchist from that of, say, the body odour of an office worker on the London Underground on a summer’s evening. Where the latter is a result of the failure to shower that morning, or the failure of a deodorant to overcome a sweaty armpit by evening, all washed down with after-work lagers, some Marlborough Lights and a kebab, the smell of these anarchists was different. It took me a while, but slowly I realised that this is the smell of a human. Or rather, this is what we smelled like before the personal hygiene industry convinced us that all and any bodily secretions, whether sweat, skin, hair, odour, saliva, mucous, pus, breath, blood, urine or excrement, are a form of waste and should therefore be contained at source, concealed at the point of emission, cleansed from the surface of our skin and perfumed around the borders of our bodies.

In his 1937 study of mining towns in The Road to Wigan Pier, George Orwell declared that a gentleman will never listen to a working man until the latter learned to brush his teeth every day. No matter the sympathy he may have for the latter’s argument, no matter how rationally he expresses it, if the breath with which his opinions are spoken ‘stinks’, as Orwell says, it will be rejected by the senses of the middle classes before it reaches whatever critical faculties they may have. This olfactory law is particularly observed within the English class system. Aesthetics, for the English, always precedes politics. Or perhaps it’s more accurate to say that it is through his aesthetic sensibilities – through the carefully educated discriminations he calls ‘taste’ – that an Englishman’s politics are formed. And though the hygiene industry has since freshened the breath of even the most hallitosic labourer, I can see no evidence that the tastes of the ruling class have been flossed of their prejudices.

When Boris Johnson was still the Mayor of London he justified his support for the demolition of the shopping centre at the Elephant and Castle roundabout by declaring – with his usual contempt for anything foreign – that it was a ‘1960s eyesore’, and even lobbied English Heritage to reject the application for its listing. The fact the surrounding community of Columbian, Ecuadorean, Peruvian, Venezuelan, Dominican, Guyanese, Nigerian, Taiwanese, Indian, Jamaican and Polish residents rely on it for food and products they not only like but can afford to buy was irrelevant to his decision, except in that removing this resource and replacing it with yet more of the corporate supermarkets that are colonising this part of South London is integral to the strategy for its social cleansing that is being advanced under the guise of its aesthetic ‘improvement’.

Similarly, when Michael Heseltine was still in charge of the Estate Regeneration National Strategy, he justified the demolition of Robin Hood Gardens by explaining: ‘It’s a very simple view: I don’t like the look of it.’ The article that reported this comment in the Architects’ Journal – supposedly the UK’s foremost architectural periodical – saw no reason to question this. And any champion of modernism and brutalism will be familiar with how even middle-class advocates of council housing will rarely end their advocacy without a lazy denigration of its architecture. Such willingly offered philistinism would be ridiculed in our liberal press if it came from the mouths of working-class council tenants voicing, for example, their aversion to ‘foreign food’; but when it comes to modernist architecture no small mindedness is out of bounds, no stereotype inapplicable, no class prejudice too embarrassing to declare out loud. Suddenly, everyone is back in the pith helmets of Empire, blabbing on about England’s ‘green and pleasant land’ and denouncing the evils of modernity. What we need, according to the new orthodoxy of British architecture that has been unquestioningly accepted by the profession, is London’s ‘traditional’ Victorian street plan; a return to a pre-modern ‘city of villages’; privatised ‘Georgian’ courtyards; a front door opening on every street; and, if not a garden to every house, then a clip-on glass balcony for every apartment. These are the design principles of a new brick ‘vernacular’ supposedly intrinsic to the soul of the British people. Everything since the Second World War – everything modern – is now bad. It’s as if the Twentieth Century never happened, or rather, was a bad dream from which we are being roughly awakened by the self-appointed custodians of our culture.

It’s a peculiarity of the English, with our suspicion of thinking in anything other than pounds and pence, that aesthetic judgments are held to be obvious. ‘I don’t know much, but I know what I like!’ might almost have been coined for the Englishman who stands, stroking his chin in suspicion, before a work of art or architecture. Never does it occur to us that what we take as given, as inherent, as – that most English of inventions – ‘common sense’, might in reality be culturally contingent, externally imposed by our education and mass media and ideologically determined by our class. Above all, we are horrified at the thought that our most dearly-held and therefore unexamined aesthetic assumptions are serving political ends at the opposite pole of their putative origins in a pre-modern England that never existed outside our nostalgia for an imaginary past.

5. Regeneration Revisited: The Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission

The latest institution of this aesthetisation of politics in housing is the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission. Announced in November 2018, the Commission is chaired by the Conservative academic and Christian moralist, Roger Scruton, who has long been a voluble critic of modernist architecture, and includes on its panel such ideologues of council estate demolition as Nicholas Boys Smith, the founding director of the Conservative think-tank Create Streets, whose anti-modernist propaganda is a constant point of reference throughout the report, and Yolande Barnes, the former Director of World Research for Savills real estate firm and current Professor of Real Estate at University College London.

This July the Commission published an interim report, the ridiculously titled Creating Space for Beauty. This is a continuation of the equally ridiculous speech delivered in November 2016 by John Hayes MP, the former Conservative Minister of State for Transport and current parliamentary link for the Commission, under the title The Journey to Beauty. And it builds on the report published in November 2018 by Policy Exchange, the right-wing think-tank, titled Building More, Building Beautiful: How design and style can unlock the housing crisis, which was co-authored by Scruton and Robin Wales, the former Leader of Newham Labour council, which has spent the last 15 years evicting residents from the Carpenters estate in Stratford preparatory to its demolition and redevelopment.

‘Place-making’, the accepted euphemism for state-led gentrification, is a major framework for the 2019 report by the Building Better, Building Beautiful Commission; as is ‘mixed-tenure’ housing, the Trojan horse of the estate regeneration programme that is replacing homes for social rent with so-called affordable rent, shared ownership and market sale properties. But the ideological groundwork for these Neo-liberal housing policies is laid in this report with earnest attempts to define beauty as ‘charm, atmosphere, life, peace, good humour and agreeable manners’, ‘serene countryside and harmonious and domestic civic buildings’, ‘a reverence for the landscape and nature’, as if Scruton and his cabal of ruthless property developers imagine themselves back at Oxford, a teddy bear clutched in one hand, dining on strawberries and Chateau Peyraguey. But just as Evelyn Waugh’s tragic lament for the passing of aristocratic class rule was founded on a barely concealed disgust for the rising proletarianisation of post-war British life, so his farcical imitators in twenty-first-century Britain have set their sights on something more tangible and lucrative than rhapsodic descriptions of the English countryside. The departed ghost of David Cameron looms large over this statement, quoted from an academic study by Robert Gifford on ‘The Consequences of Living in High-Rise Buildings’:

‘Many, but by no means all, residents are more satisfied by low-rise than by high-rise housing. High-rises are more satisfactory for residents when they are more expensive, located in better neighbourhoods, and residents chose to live in them. Children are better off in low-rise housing; high-rises either restrict their outdoor activity or leave them relatively unsupervised outdoors, which may be why children who live in high rises have, on average, more behaviour problems. Residents of high-rises probably have fewer friendships in the buildings, and certainly help each other less. Crime and fear of crime probably are greater in high-rise buildings. A small proportion of suicides may be attributable to living in high-rises.’

Which is to say, 45-storey property investments for global capital and the housing of wealthy foreign students in the Elephant and Castle are okay, but the housing blocks of the demolished Heygate estate were not. The brutalist Barbican estate is fine for the wealthy residents who can afford its astronomical sale prices, rents and service charges, but the Golden Lane council estate down the road is potentially pullulating with suicides. The Balfron Tower is retro-chic when its new residents are the Canary Wharf bankers at whom its newly-renovated apartments have been marketed, but a breeding ground for criminals when they were tenants of Tower Hamlets council.

Although – quite ludicrously in a 90-page report – no mention whatsoever is made of the Estate Regeneration National Programme that threatens or has already demolished around 250 estates in London alone, and many more across England and Wales, the implications of the report for council estates is clear when we follow the consequences of Professor Gifford’s argument. If high-rise housing, as he asserts, is good for the rich but bad for the poor, then the council estates on which high-rise housing for the poor is built should be demolished and replaced with high-rise, higher-density and above all high-value properties for the wealthy. By the same logic, since low-rise housing is good for the poor, and Inner London – according to the accepted political orthodoxy propagated by developers – requires dense, high-rise development, then the logical conclusion is that estate residents (who in the accepted stereotype are all poor) must be moved out of Inner London – indeed, must be compelled to leave for their own good. Otherwise, apparently, we’re facing an epidemic of badly-behaved children, friendless and uncaring neighbours, crime and the fear of crime, and mass suicide. And the cause of all this, according to the Commission, is not a lack of investment in jobs for our inner-city youth, not the largest cuts to welfare benefits in generations, not aggressive and racist policing of council estates, not the rise of gang culture following disinvestment in apprenticeships and community facilities, and not the managed decline of council estates by councils intent on demolishing them for profit – but because poor people live in high-rise buildings.

Professor Gifford teaches in the Department of Psychology and Environmental Studies at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, Canada, and his report was written in 2006; so it’s not immediately apparent what application his generic study can possibly have to the particularity of the UK housing crisis 11 years into the fiscal policies of austerity and 22 into a national programme of estate demolition. Like most academic studies, this one relies on other academic studies for its opinions, and its empirical evidence (derived from these studies) skips from New York, Chicago, Vancouver and Toronto to Glasgow, Singapore and Hong Kong, but says absolutely nothing about London. Yet much of the commission’s implied opinion and future recommendations on London’s council estates appears to rest on Gifford’s unsubstantiated and inaccurate claims: on subjective assertions about residents’ apparently universal preferences for low-rise housing; on technically false claims about a lack of play amenities for children on high-rise blocks designed precisely to free up the land around them for their recreation; on clichés about the apparently causal equation between architecture and anti-social behaviour rather than the latter’s far more likely socio-economic origins in poverty and a lack of educational and career prospects; on demographically inaccurate generalisations about the economic status of estate residents, which includes a broader social mix than just about any other form of urban housing; on subjective opinions about the lack of friendships formed on the close-knit communities that are in reality brought together precisely by the communal spaces of council estates, rather than separated by the strict division between private and public space that obtains on terraced housing; and on lazy stereotypes that equate council estates with criminal behaviour when the 2015 Index of Multiple Deprivation shows no consistent spatial relationship between London’s council estates and higher levels of criminality.

The fact that Professor Gifford attributes all these putative social ills and design flaws to ‘high-rise buildings’ rather than council estates serves the Commission’s use of his study for their own political ends; but his description of wealthy neighbourhoods with that most middle-class of euphemisms – ‘better’ – reveals the class origin – which is to say, the aesthetic basis – of his prejudices. Like the rest of the Commission’s report, this Orwellian division of the suitability of a housing typology into ‘poor residents bad, rich residents good’ is nothing more than the expression of class disgust – the same disgust that repelled Orwell from the breath of the miners he otherwise admired; and its quotation at length in a report supposedly about restoring beauty in architecture is an attempt to mobilise that disgust in the service of a social, political and above all economic programme to socially cleanse working-class communities from the UK’s inner cities, demolish or privatise what’s left of our stock of social housing, and replace it with ‘better’ – which is to say, ‘more expensive’ – neighbourhoods that will drive up the value of the land on which it is built.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that in a 90-page interim document laying out the principles of new development that will presumably, in the final recommendations due this December, include policy on the new housing developments that are supposed to guide us through and out of the increasing crisis of housing affordability in the UK, a single, half-page paragraph (9.2) is devoted to the question of affordability, and what it says is meaningless tokenism: ‘People need to know they will have somewhere to live which they can afford’. Thank you for that. But in reality, it is precisely the unaffordability of the residential properties that the Building Better, Building Beautiful commission has been formed to justify building on the ruins of our inner-city council estates that will determine the measure of the class that invests in, accumulates capital from, and occasionally even lives in them.

Capital is the measure of the human under capitalism. The 20-storey towers of three-quarters-of-a-million-pound luxury apartments that Notting Hill Genesis plans on building overlooking Burgess Park in Camberwell are an ideal typology for the accumulators of capital, but the 14-storey blocks of council housing on the Aylesbury estate being demolished to make way for them are judged to be not on a ‘human scale’ when the humans occupying them cannot afford to buy or rent their high-value replacements. On such market fundamentalism is the aesthetics of social cleansing founded. Indeed, in an echo of Southwark council’s lawyers, the Commission quotes Ben Page, Chief Executive of the market research company Ipsos MORI, unilaterally declaring on behalf of the British People that: ‘The broad preference is against tower blocks, in favour of the vernacular, in favour of human scale.’

Conclusion

The religious fundamentalism of Islamic State ethnically cleansing Northern Iraq and Syria, like the market fundamentalism of the British State socially cleansing the UK – and which, as in Syria, is leaving a trail of homeless refugees in its own land – is not only motivated by the ideological zeal of the vandals. Like Islamic State’s destruction of pre-Islamic gods and their monuments, the demolition of England’s council housing has a political function as propaganda for the Brave New World that destruction heralds. For Islamic State it was and is the worldwide Caliphate it hoped to establish; for the governments of Britain’s Parliamentary Democracy it is the monopoly capitalism that has colonised the world. Behind its loudly declared allegiance to multiculturalism and plurality, Western democracy is as mono-cultural, conservative, reactionary and revisionist as its new ideological enemy, Islamic fundamentalism: tolerating no deviance from its dictates, ruthless in its punishment of apostasy, and shirking no violence in its suppression of other ideologies, whether polytheism or socialism. The monuments to the latter – or at least the closest the UK ever came to it – including our council housing, our national health service, our nationalised industries, utilities and transport systems, our free education and our welfare system, and the memories they hold of an alternative way of understanding the world and how we live in it, global capitalism is intent on reducing to rubble. Today, following the recapture of Palmyra in March 2017 by the Syrian Army, the ancient monuments are being reconstructed from the ruins. In London, where the holy war on social housing continues unchecked, the vandalism continues.

Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and after more than four years of work we still have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

One thought on “The Smell of an Anarchist: The Aesthetics of Social Cleansing”