This case study continues on from The Regeneration of Ham Close. Part 1: What the Green Party has learned from Labour.

In the first part of this case study I looked at the justifications given to me by Andree Frieze, the Green Party ward councillor for Ham, Petersham and Riverside Drive, for demolishing Ham Close estate, drawing on the Ham Close Uplift Programme webpage of June 2019, the current proposal for the redevelopment, the Richmond Housing Partnership (RHP) and Richmond council consultation document October 2016, and the report by the Prince’s Foundation, Vision for the Future of Ham Close, published in October 2014.

Finally, there is the second document to which Andree Frieze has referred me, the Ham Close Uplift Regeneration Strategy, which was published in July 2015. This was produced by BPTW Partnership, an architectural practice that describes itself as ‘a UK industry leader in urban regeneration’. In addition to the proposed redevelopment of Ham Close estate, BPTW was responsible for designing the disastrous redevelopment of the Loughborough Park estate in Brixton that was so opposed by residents. This resulted in 390 housing association homes for social rent being demolished by the Guinness Partnership and replaced with 487 dwellings, of which 354 (70 per cent) will be for affordable and intermediate rent (as an example of which, one evicted tenant’s rent was increased from £109 to £265 per week), and 133 properties (30 per cent) will be for shared ownership, with 2-bedroom properties on sale for around £520,000. BPTW also designed the controversial regeneration of the Pepys estate in Deptford, where 60 per cent of the 285 new dwellings by Hyde Housing Association are loosely designated on BPTW’s website as ‘affordable’, with the remaining 40 per cent shared ownership properties. The result of this scheme, which included selling Aragon Tower to Berkeley Homes, was a loss of 366 secure council tenancies across the estate. So BPTW Partnership has form with helping housing associations to which councils have stock-transferred their estates to maximise the value of the land by demolishing the social housing and replacing it with affordable, shared ownership and market-sale properties, which is exactly what RHP are proposing for the Ham Close estate.

It’s BPTW’s report on Ham Close, however, that I want to focus on in Part 2 of this case study, and in particular the justifications they give for demolishing the estate and replacing it with a development that will substitute affordable for social rent, and offer intermediate rent, shared ownership and market sale properties as some sort of gesture toward housing need in Richmond.

So that it’s clear, this strategy report was commissioned by the previous Conservative administration of Richmond council. However, the report’s justifications for removing the option to refurbish Ham Close estate and leave residents with a choice between the continued managed decline of their homes and the demolition and redevelopment of the entire estate has been seamlessly adopted by the Liberal Democrat administration of Richmond council that was elected in London’s local elections of May 2018. In exactly the same way, the new Liberal Democrat council in neighbouring Kingston has continued its Conservative predecessor’s decision to demolish and redevelop the 800-home Cambridge Road estate. Here again we see that, despite the opposition to estate demolitions by Liberal Democrat, Green, Labour and Conservative councillors when in opposition, once in power these parties find a sudden harmony in their unanimous agreement that demolition and redevelopment, and not refurbishment and infill, is the only option for estate regeneration.

So, what is the role of the architect in this cross-party programme of social cleansing, estate demolition and privatisation of UK housing provision? I wasn’t surprised to see that the consultancy employed by Richmond Housing Partnership to carry out the consultation process with residents of Ham Close estate was Newman Francis. ASH has come across and exposed their entirely fraudulent practices in our opposition to the plans of the Guinness Partnership to demolish the Northwold estate in Hackney. Among its many examples of bad practice, most glaring was that Newman Francis was supposedly ‘consulting’ residents on options that had already been narrowed down to demolition and redevelopment a year earlier. Once again, the consultation process, in this context, is nothing more than the manufacturing of resident consent for a plan that has already been decided upon by the council, housing association or developer, and I don’t expect the procedure was any different at Ham Close.

In this consultation process, the role of the architect is crucial in the planning and visualising of the various proposals in depictions of middle-class enclaves socially cleansed of social housing tenants (above), but also in providing the justifications for the pre-selected option of demolition, which is typically expressed in architectural language that will often mean little to residents. We find these generic justifications used again and again in reports. They rely on subjective expressions of aesthetic judgments offered as if they were objective truths. They express the prejudices of middle-class taste and morality informed by decades of negative stereotypes about council estates and the predominantly working-class communities that live on them. They are conveyed through blatantly biased representations of estates before and after their demolition and redevelopment, some of which we have already looked at in Part 1 of this study, in the artist’s impressions in the Prince’s Foundation report. In short, they have no place in what should be an objective assessment of the social, financial and environmental costs of an estate regeneration scheme; and the almost universal collaboration of UK architectural practices in producing these reports is a total abnegation of their duties as architects, and the opposite of a socialist architecture.

As an example of this, the following reasons are given in this consultation document by BPTW Partnership as justifications for the demolition of Ham Close estate. The first four are taken directly from the Prince’s Foundation report, Vision for the Future of Ham Close, and were supposedly agreed upon by residents and stakeholders during the consultation process:

- ‘Improvements should be made to the area to enhance its setting and character, and to reduce the perception of anti-social behaviour.’

It’s unclear why the setting and character of Ham should require enhancing more than, say, Belgravia; or how demolishing a part of that setting will improve its character. But the definition of anti-social behaviour has been expanded over the past twenty years by the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, the Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003, and the Anti-Social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Act 2014 to include any conduct that ‘causes, or is likely to cause, harassment, alarm or distress’. Such acts include begging, rough sleeping, drinking alcohol, loitering, swearing, shouting and urinating, but also include displaying a sign in public that another member of the public finds offensive. Apart from the fact that we should be opposing such legislative constraints on our human rights rather than using them to implement the demolition of social housing, no-one has yet produced any evidence to support the argument that architecture, whether that of modernist estates or that of terraced housing, is a cause of such behaviour.

Despite this, the unsubstantiated and disproved association of anti-social behaviour with council estates is one of the first arguments made by councils, housing associations and developers for demolishing them. It is incumbent upon a socialist architecture to interrogate and where necessary expose the lack of evidence for this urban myth, and not unquestioningly to repeat it as an objective truth. As to reducing the ‘perception’ of such behaviour, this is a sophistry that should have no place in an objective assessment of whether the homes of around 500 people should be demolished.

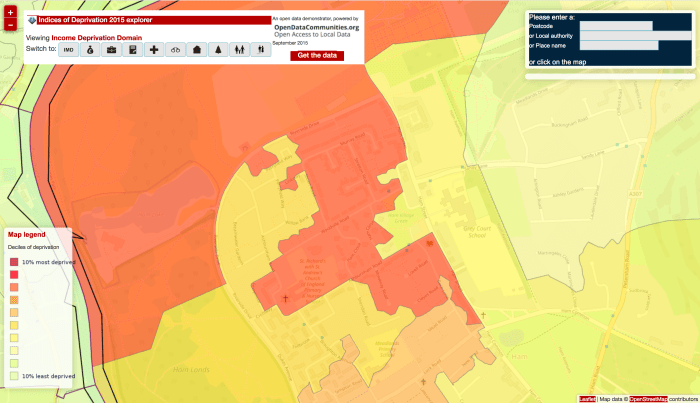

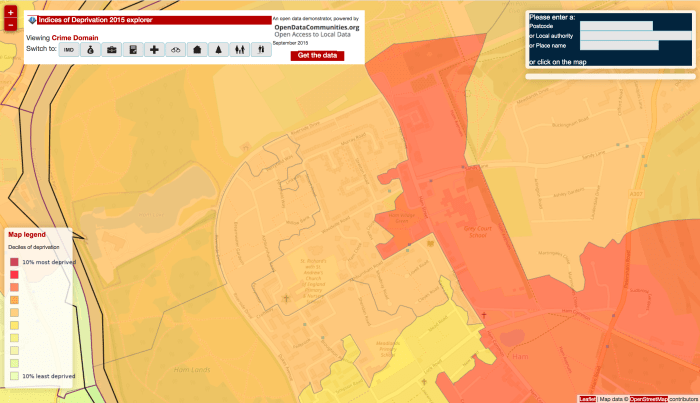

What does have a place in such an assessment is an objective record of the level of criminal activity on Ham Close estate, and the 2015 map of Indices of Multiple Deprivation for Ham Close reveals that, in common with the terraced council housing to the north and sough, the estate does have a higher level of income deprivation (the map on the left below) and unemployment than the Wates estate to the west with its more middle-class residents. However, the crime levels on Ham Close estate are no higher than the rest of Ham (the map on the right below). In fact, this map shows that there are higher crime rates around Ham Common to the south, but we don’t hear Richmond council calling for the demolition of the multi-million-pound Victorian townhouses and Georgian mansions that border its green spaces, claiming their architecture is the cause of anti-social behaviour and crime. In fact, this lack of evidence for an equation between crime and council estates accords with every estate ASH has ever located on this interactive map; and, indeed, housing estates typically have a lower level of criminal behaviour than the surrounding neighbourhood of terraced housing.

The ‘perception’ that anti-social behaviour is somehow endemic to council estates exists only in the eyes and minds of those who do not live on them, in the media and entertainment industries that promote this perception, and in particular in the reports of councils, housing associations, developers, consultants and architects looking for reasons to demolish them. Behind a concern for reducing criminality that is supposedly consequent upon a type of modernist architecture, there is only the deliberate trading in negative stereotypes, and a financially driven desire to move working-class households off potentially lucrative land.

- ‘Redevelopment could provide a centre for Ham Close and Ham, as well as help retain and improve its village feel.’

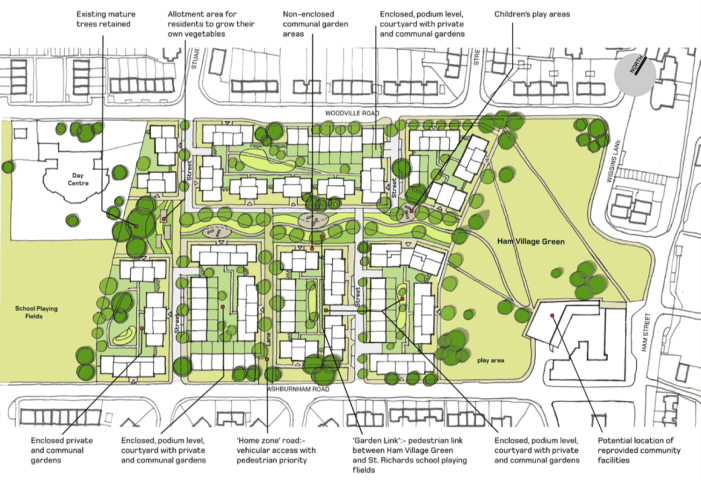

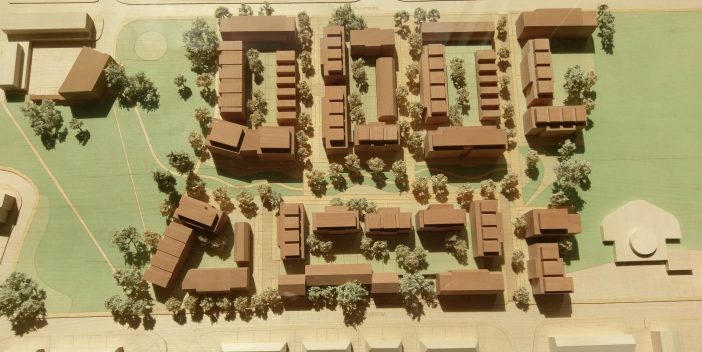

Redevelopment only follows demolition, and before claims are made that demolishing 192 homes would provide a centre, either for the demolished estate or for Ham as a whole (whose already existing ‘centre’ is the church, surrounding green and parade of shops to the west), we should ask for whom this centre is being created in what is commonly termed ‘place-making’. Given the lack of transparency about what demolition and redevelopment will cost and therefore what will get built in place of Ham Close estate, it’s possible and more than likely that the new centre will be exclusively for those who can afford the increased rental and service charges on the proposed affordable housing and the hugely increased house prices on the proposed shared ownership and market sale properties. In contrast to the dynamic, modernist layout of Ham Close estate whose green spaces are open to the public, the proposed masterplan by BPTW, which accords with the ubiquitous Create Streets model designed to realise the potential ‘uplift’ in land values to which the title of this report refers, and which has claimed a considerable strip of land from the two neighbouring schools, is an unimaginative, dense rhomboid of inward-looking blocks set around what it designates as ‘enclosed, private and communal’ courtyards completely at odds with the permeable character of the rest of the well-loved Wates estate. Again, it’s unclear how this privatisation and development of public green space will in any way contribute to the ‘village feel’ of a modernist estate.

- ‘The buildings in Ham Close are seen as disconnected from Ham’s village setting. An improved layout could better integrate the estate into the wider community.’

The obvious question is to ask ‘seen by whom?’ Ham is a composite of some nineteenth- century and older buildings around Ham Common to the east, the 1950s semi-detached housing to the immediate north and south of Ham Close, and the 1960s Wates estate to the west. Apart from the older buildings around the Common, Ham does not have a ‘village setting’, no matter how much the Prince of Wales and Conservative think-tanks like Create Streets would like to impose it upon this community. The phrase itself, ‘village setting’, is an ideological one employed by promoters of the market to oppose the modernist architecture of post-war council estates as a supposedly unredeemable failure. From our extensive experience of attending consultations and reading their surveys, ASH knows how organisations like the Prince’s Foundation and Newman Francis can extract agreement from residents to statements they have presented to them, and this sounds very much like an example of this manipulative and fraudulent practice. Even if the residents of the estate (rather than the estate the Prince’s Foundation recommends demolishing) require better opportunities for integration into the wider community – an assertion for which this document provides absolutely no proof whatsoever – socially cleansing that community through demolishing their homes and replacing them with unaffordable housing is clearly not the way to do that.

- ‘Community facilities could be improved, for instance by collocating the youth centre, clinic and library.’

Perhaps they could, and combining the youth centre, whose current location at the centre of the Ham Close estate is eminently practical, the equally conveniently located clinic on Ashburnham Road (below), and the library on the corner of Ham Street would free up considerable land for infill development on the estate without the necessity for demolition. Not only would this remove the unnecessary financial cost of demolishing structurally sound homes, but a portion of the new infill development could generate the funds to carry out the neglected refurbishment of the existing homes, pay for any required renovations, increase overall housing capacity on Ham Close by 50 per cent or more, and allow more of the new residential development to meet the actual housing needs of Ham and Richmond, rather than the shared ownership and market sale properties necessary to pay for the huge costs of demolishing and replacing the 192 existing homes. What improving these community facilities doesn’t do is provide a justification for the demolition of the rest of the estate.

On the basis of these so-called key principles, which are in fact founded upon stereotypes, prejudice, factual inaccuracies, manipulation and false reasoning, the Prince’s Foundation’s ‘Vision’ for Ham Close produced the following justifications for demolishing the estate:

- ‘Ham Close itself is an anomaly in a garden village setting. Connecting it and offering integrated green space would be beneficial, as would its development along a traditional street-based housing model. Better integration of Ham Close with its surroundings is a key concern.’

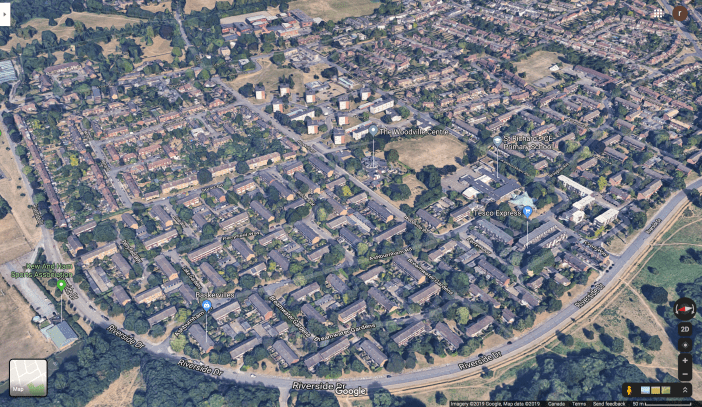

In actuality, the layout of Ham Close is consistent with the rest of the Wates estate (below), which is laid out in an open and permeable arrangement of 2- and 3-storey housing blocks set at right-angles to each other and typical of modernist housing estates of the 1960s, and nothing like a traditional street-based housing model. In a blog dedicated to the estate, in which he has lived since 1966, Matthew Rees writes:

‘What makes Wates estate so attractive is the overall design that created lots of open spaces between the houses and paths to move around them.’

Rather than imposing their own prejudices and preconceptions about the supposed character of the Wates estate, the Prince’s Foundation should have asked the people who live there what they thought about their community and whether Ham Close constitutes, as they rather arrogantly assert, an ‘anomaly’. The only benefit from demolishing Ham Close and redeveloping it on a street-based model is that it would increase the density of properties and with it the profits from their sale for RHP and its investment partners. The assertion that the modernist layout of Ham Close means it is not integrated with the rest of the Wates estate, and that this constitutes a concern for anyone other than the developers, is completely lacking in foundation or proof.

- ‘Overlooking and enclosing Ham Green would enhance safety and use.’

The perception that all spaces within or around a council estate are unsafe and require to be overlooked by residents and neighbours who act as a form of internal surveillance betrays, once again, the negative stereotypes about the working-class communities that live on estates in the minds of middle-class professionals. The primary threat to such communities comes not from within the estate from those outside who wish to socially cleanse residents from the land on which their homes are built. No-one talks of dimly-lit terraced streets in South Kensington requiring overlooking, or of demolishing the homes of its wealthy residents as a way to enhance the safety and use of Kensington Gardens. Once again, this is a class prejudice employed to further the financial motivations of developers and investors, and has no place in an objective report on the refurbishment options open to residents.

- ‘Tenants and leaseholders are concerned about damp, ventilation and the ageing of the buildings, and accept that these issues must be addressed. A longer-term fix was preferred. Any work at Ham Close would be based on a long-term solution rather than a short-term ‘fix’.

If residents homes are affected by damp and poor ventilation, these issues can be addressed without the need to demolish them. Indeed, new developments, hastily thrown up across London, report the same problems; so opposing a short-term fix to a long-term solution is inaccurate. Damp has many causes, including leaking roofs allowing water into the interior of the building, and this can and should be addressed by RHP maintaining the repair of the roofs. Another cause is the lack of ventilation. This can be caused by poorly designed or fitted replacement windows, as happened on Central Hill estate in Crystal Palace, which lacked the trickle vents that allowed air into residents’ homes. Another cause is a lack of insulation between the cold exterior of the building and the warm interior, known as cold-bridging. Again, this is something ASH has experience of in even so-called luxury new developments; but it can be addressed through a programme of refurbishment that, with all the other benefits of the Decent Homes Standard plus, will cost around the same as, or less than, demolishing the homes. In no respect does damp and poor ventilation constitute a reason for demolishing residents homes, and architectural practices who collude with consultants and landlords telling residents this is the case are lying to them. As for the eagerly repeated myth that 60 year-old reinforced concrete buildings such as those at Ham Close have come to the end of their natural lifespan, this again has no basis in truth, and consultants and landlords who use this excuse to justify demolishing residents homes are, once again, lying to them. Maintaining, repairing and refurbishing any building, including residential dwellings, is not an option but a simple fact about how buildings work. No building would function for more than a few decades without that upkeep, and representing doing so as a ‘short-term fix’ is, once again, a falsehood that contradicts everything about architecture, and not only that of Ham Close.

In addition to these reasons, not one of which has a basis in fact, BPTW’s strategy report adds the following:

- ‘A desire to help transform this estate in order to deliver a high quality environment in addition to homes for residents of the estate that are highly sought after for many decades to come (sic).’

I hope BPTW’s architecture is better than their grammar; but although quality should be an aim of any new contribution to the built environment, it should not come at the prohibitive cost of new housing provision, which in the case of the townhouses proposed by BPTW (above) will be anything up to three-quarters of a million pounds; and the emphasis on high quality in architectural discourse has been employed to conceal the blind spot of housing affordability. Homes should not be ‘highly sought after’, which betrays the market framework within which the proposed new properties are being built; they should be available according to the housing needs of constituents – precisely that framework in which council housing such as Ham Close was originally built and continues to function. ‘High quality’ and ‘highly sought after’ are part of the salesman’s patter of estate agents, and should have no place in a strategy framework for housing provision by a registered provider of social housing or a local authority.

- ‘The existing flats at Ham Close are of ‘Wimpey no fines’ construction with poor insulation leading to condensation issues, in some flats, in addition to there being no lifts.’

Although there is no explanation in this report of what ‘Wimpey no-fines’ means, which makes this justification opaque to residents, this refers to a novel, post-war, prefabricated method of construction that used congregate without fine aggregate. Interior walls were a mixture of conventional brick and blockwork, with the external shell of the building rendered to make it weatherproof. Wimpey’s version of this method was particularly successful. However, in the 1980s, when political opinion turned against the threat social housing presented to the property market, the long-term structural soundness of this construction method was questioned. In response, Parliament commissioned a report which in 1989 found that buildings constructed using this method were structurally sound, and that the insulating properties of the no-fines walls were reasonable when compared to buildings of the same period. Instead, the poor insulation was attributed to poor windows and poor heating, and subsequent improvements to the windows and heating facilities brought the houses up to modern living standards. The Wimpey no-fines design is now seen as largely vindicated. The attempt by BPTW Partnership to revive the unfounded prejudice against this construction method comes from the same desire to discredit social housing in order to clear the land it is built on for private development, which is precisely what RHP are trying to do to the Ham Close estate. As for the lack of lifts, the ‘refurbishment and partial redevelopment’ option in the report by the Prince’s Foundation demonstrated that these can quite easily be added, as they have been on numerous estates across London.

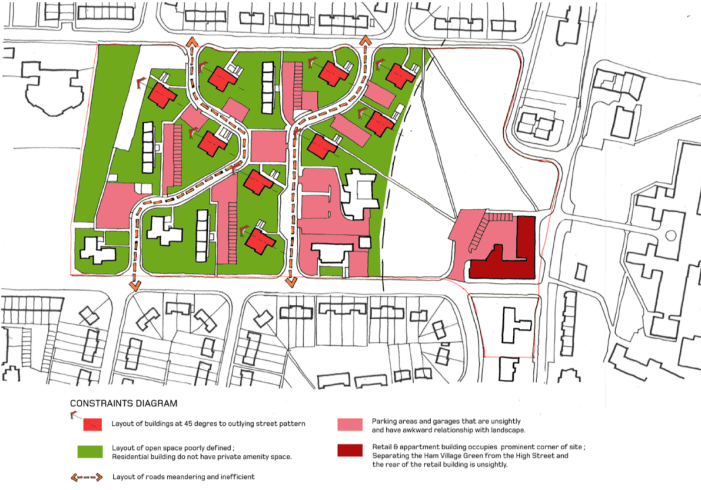

- ‘The buildings appear to be arranged in a disparate layout due to the five storey blocks being orientated at forty five degrees to the other buildings.’

This is close to ridiculous as a justification for demolishing an estate, and calling the combination of the north-south axis on which the point blocks are aligned with the north-west by south-east axis of the slab blocks ‘disparate’ doesn’t hide the transparency of this attempt to identify a fault in design that simply is not there.

- ‘The areas between buildings are accessible to the public. There are no residents private gardens and a lack of fencing means that open space is not secure.’

The issues associated with public spaces, which as we have seen are no greater on Ham Close than anywhere else in Ham, can be addressed through thoughtful architectural interventions. Fencing the land off, as became council practice in the 1980s when council housing was under threat by the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher because of its barrier to the private property market, is not a solution, as it fences the green spaces off from residents as well, and fosters the false impression, which continues to this day, that council estates are no-go areas to be avoided by the general public. Privatising this public space, as the designs by BPTW propose, is an equally poor solution, and a Trojan Horse in the stealth privatisation of public land that estate regeneration schemes such as this are implementing. Between these two spaces, public and private, there is a third choice, which is communal areas not owned by individual residents who are, nevertheless, collectively responsible for its occupation, use, layout and maintenance.

A socialist architecture would not accommodate the further privatisation of what’s left of London’s public land, but propose, in collaboration with residents and a landscape architect, ways to create communal gardens that would encourage social interaction between the residents of Ham Close while addressing the issues of public space that is open to abuse when not maintained by the landlord and local authorities whose jobs it is to do so. Indeed, the numerous mature trees on the public spaces between the point and slab blocks of Ham Close (below), all of which will be torn down by RHP’s plans with huge negative consequences for the area’s wildlife and biodiversity, are an ideal starting point for designing and inhabiting such communal areas. In no respect are its public spaces a justification for the demolition of Ham Close estate.

- ‘The existing estate roads are unwieldy in layout and appear out of character with the more regular street pattern of surrounding estates and road layouts.’

This is another factually inaccurate statement. While Ham Close sits between the parallel Ashburnham Road to the south and Woodville Road to the North, the Wates estate and Ham in general is characterised by its irregular roads that wind in curves and crescents through the housing blocks (below). Far from being ‘unwieldy’, this irregular pattern contributes to the safety of the neighbourhood, and in particular for children playing on and around roads on which cars are forced, precisely because of this street layout, to reduce their speed. In this respect, as in so many others, Ham Close is in fact ‘in character’ with the rest of the Wates estate, and BPTW’s assertion to the contrary is not only factually incorrect but a deliberate attempt to fabricate evidence to justify the demolition of an integral part of Ham.

- ‘The Youth Centre building is a largely single storey building that is constructed of reinforced concrete. The decoration of the building appears to be in need of refurbishment.’

It’s unclear how the construction of the dynamic, brutalist design of the Ham Youth Centre (below) is a justification for demolishing it and the surrounding estate, except insofar as the term ‘concrete’ has become a shorthand used by developers and local authorities to stereotype the communities that live in post-war council estates. Within this discourse, which is a smear campaign in everything but name, ‘concrete’ has become a metonym for anti-social behaviour, crime, unemployment, poverty, dirt, squalor, and the other negative myths with which the building industry and its lobbyists in our local authorities and government have sought to demonise council estates, and has as little basis in fact as these other smears against the predominantly working-class communities that live in concrete residential buildings. In other words, trading in such stereotypes to argue for the demolition of the homes of residents has no place in a regeneration strategy report produced by an architectural practice. And if the Youth Centre is in need of refurbishment, then a proposal for such refurbishment should be made.

- ‘The retail centre occupies a prominent corner site at the junction of Ashburnham Road and Ham Street. The rear of retail building is unsightly.’

Once again, the question to be asked in response to this assertion is ‘unsightly for whom?’ In any case, purely subjective aesthetic judgements have no place in what should be an objective strategy for the regeneration of Ham Close estate. If such aesthetic judgements are sought, they should come from the residents of Ham, not from architects manufacturing reasons to increase their profits from a scheme of demolition and redevelopment from which they will expect to take a percentage fee of what will be a £150-200 million project, rather than an £8 million programme of refurbishment. As it is, the local community has already taken the initiative to decorate the side of the retail buildings to which RHP wants to move the estate’s community buildings with a mural (below), and presumably doesn’t need BPTW to tell them what is ‘unsightly’ about their community.

- ‘The full redevelopment option presents an opportunity to re-provide the service facilities in a new purpose built community hub building and will offer operational improvements in terms of access and opening times.’

For anyone who lives in the currently being gentrified neighbourhoods of Dalston, or Brixton, or Peckham, or Deptford, the promise of a ‘community hub’ has all the negative connotations that the term ‘council estate’ has for speculators in high-value residential property; except that, rather than depressing land values, a community hub is a means to raise them for landlords and investors at the expense of rent and rate payers. But leaving aside this terminology of place-making that is a euphemism for social cleansing, the only justification for moving the youth centre, clinic and library to the area behind the parade of shops on the corner of Ashburnham Road and Ham Street is to free up the land for infill development that will meet Ham and Richmond’s housing needs. It should not be used as a justification for demolishing Ham Close estate and replacing it with market sale, shared ownership and affordable rent housing that will force the majority of existing residents off the estate and fill the pockets of RHP and its development partners.

- ‘Whilst the ‘Ham Village Green’ is clearly highly regarded by residents and local people, the regeneration of the Ham Close estate will provide an opportunity to enhance the setting of the green.’

An opportunity to ‘enhance the setting of the green’ (whatever that may mean in practice and why ever it should be necessary) should not be justification for the potentially prohibitive increase in housing costs for residents of Ham Close consequent upon the demolition of their homes. Like the mural on the retail block that borders the green, a playground for children in the south-east corner of the green has already provided what one would assume is a welcome addition (above). It is unclear from BPTW’s masterplan whether this playground will be retained or reprovided; but their computer-generated vision of the new green (below) shows it being ‘enhanced’ only for those who can afford the market sale properties that, following standard practice in mixed-tenure estate redevelopments, will line the green with 6-storey blocks, obscuring the views for the segregated affordable housing blocks located behind. Indeed, one of the primary reasons for Ham Close being identified for a regeneration scheme that has inevitably led to a decision to demolish and redevelop the estate, is the value uplift that views of Ham Green will bring to the luxury apartments that will have exclusive access to that view in the dense, continuous line of properties from which RHP and its private investors will take the majority of their profits.

Since publishing Part 1 of this case study, the following e-mails have been sent to me by Andree Frieze recording her attempts to get answers from Richmond council to some of the questions about the regeneration of Ham Close I started asking her at the beginning of June.

E-mail, 4 July, 2019

Dear Mandy

Can you help me with these questions please? If you are not the right person to answer them, who should I send them to?

Has the council made the financial viability assessment of the redevelopment scheme available for public scrutiny, as you should since this will determine what gets built in place of the existing estate?

Has the council produced an impact assessment of the social, financial and environmental costs of the demolition and redevelopment of the estate to residents, neighbours who are affected by the scheme and the council?

Has the council produced a refurbishment and refill option for the consideration of residents that would actually increase the number of homes for social rent rather than reduce them, and in doing so meet the borough’s actual housing needs?

Sufficient amenities to offset the increased burden on services such as schools, clinics and roads isn’t something that should be deferred to the future attentions of councillors, no matter how conscientious they claim to be, but must be an integral part of the planning requirement of the council you represent. Has the council you produced an impact assessment of this increase and made its amelioration a condition of granting planning permission to the scheme?

Thank you very much.

Kind regards

Andree Frieze

Green Party Councillor, Ham, Petersham & Richmond Riverside

E-mail, 15 July, 2019

My apologies Councillor Frieze

I have copied in Charles who will respond in more detail shortly. With regards to what the council has done and considered, for the most part these issues have sat primarily with RHP as owners of the estate. But we will get back to you as soon as possible.

Regards

Mandy Skinner

Assistant Chief Executive at Richmond and Wandsworth Councils

E-mail, 16 July, 2019

Thank you Mandy. I look forward to hearing from Charles.

In the meantime, do you know if RHP is planning to put the whole regeneration to the residents in a vote, as brought in by the Mayor of London in July 2018?

Kind regards

Andree Frieze

Green Party Councillor, Ham, Petersham & Richmond Riverside

E-mail, 17 July, 2019

Dear Councillor Frieze

Apologies for the delay. Please find responses to your queries.

The Mayor’s guidance regarding resident ballots was published in July 2018 following consultation. Ham Close has formal exemption as RHP had a funding contract signed prior to this.

Has the council made the financial viability assessment of the redevelopment scheme available for public scrutiny, as you should since this will determine what gets built in place of the existing estate?

The redevelopment of Ham Close will be carried out by Richmond Housing Partnership (RHP), as such viability falls with them. In November 2018 Cabinet agreed for the Council to enter into a Collaboration and Land Sale Agreement with RHP, while this process is on hold while RHP re-procure a developer partner (please see an update on the Ham Close website), the scheme’s viability and ultimately what is built (circa 450 units) is integral to this. Once RHP procure a developer partner they will carry out further viability work as they look to develop a scheme based on the 2015 masterplan.

Has the council produced an impact assessment of the social, financial and environmental costs of the demolition and redevelopment of the estate to residents, neighbours who are affected by the scheme and the council?

The Council produced an Equality Impact and Needs Analysis (EINA) which was included with the November 2015 Cabinet report. However, as above, the redevelopment is being carried out by RHP and so it falls to them. The Council will update their EINA as required going forward.

Has the council produced a refurbishment and infill option for the consideration of residents that would actually increase the number of homes for social rent rather than reduce them, and in doing so meet the borough’s actual housing needs?

Refurbishment and infill would be for RHP to consider as owners of the buildings and land between the blocks. In the past a refurbishment option was considered but was considered unaffordable.

Sufficient amenities to offset the increased burden on services such as schools, clinics and roads aren’t something that should be deferred to the future attentions of councillors, no matter how conscientious they claim to be, but must be an integral part of the planning requirement of the council you represent. Has Richmond council produced an impact assessment of this increase and made its amelioration a condition of granting planning permission to the scheme?

Consideration of the community facilities is ongoing and will be an important part of the Collaboration Agreement between the Council and RHP, ensuring the re-provision of existing community facilities on Ham Close and offer some space for the re-configuration or provision of new services. The Council will be carrying out some engagement events which will help inform a specification for the new community building/space requirements.

Kind regards

Charles Murphy

Senior Project Officer

Serving Richmond and Wandsworth Councils

E-mail, 18 July, 2019

Dear Simon

I have heard back from Richmond Council officers with some answers to your questions. As you will see, they are not complete, so I have forwarded them on to RHP to get fuller answers. I have also asked them to put the scheme to the residents for a vote despite being formally exempted from the Mayor of London’s policy on ballots due to timescale.

In addition, I have the details of the new Chair of the Ham Close Residents Association. Would you like me to set up a meeting for the three of us?

Kind regards

Andree Frieze

Green Party Councillor, Ham, Petersham & Richmond Riverside

The other responses the publication of Part 1 of this study received were from residents of Ham Close estate, which I’m including here, both because they range the gamut of residents’ reaction to the truth about what the demolition of their estate will mean for them, and because they raise questions that I want to address.

Comments on ASH website, 18 July, 2019

Great article and hopefully with you on board we can start getting some answers as, yes, a year-and-a-half on I still have not had my post replied to, I’m still in the dark and I don’t know what is going on! Very, very scary, as this is my children’s home and to not know where we will be in the future is extremely unsettling.

Lisa Sherwood

Resident of Ham Close

PTFA Chair at St. Richard’s Primary School

I live on Ham Close and have done for over 20 years. I would like a property that is insulated, not black with mould and damp, has a lift because my mobility is bad, more room for a wheelchair and is basically not unfit for purpose. If you are going to poke your nose into our affairs make sure you do it right. We have agreed to stay in situ during building works and a majority of us just want the regeneration to go ahead with out any more holdups.

Mandy Jenkins

Resident of Ham Close

I said earlier that the equation between council estates and anti-social and criminal behaviour exists only in the minds and eyes of those who do not live on them. Unfortunately, this is not entirely true. This perception is also instilled in the minds of residents themselves, partly by the incessant negative representation of estates and their communities in our media and entertainment industries, but also in response to the managed decline of the estates. Andree Frieze has also sent me the text of a presentation by one of the above residents, Mandy Jenkins, repeating many of the negative perceptions about Ham Close given in the reports above as a reason for its demolition above, and in much the same language. Out of respect for Ms. Jenkins and in sympathy with her perfectly valid concerns about the conditions under which she has to live on an estate undergoing managed decline and a lack of maintenance by her landlord, but which she still clearly loves dearly, I will quote from her presentation here at length:

- The majority of people enjoy living in Ham close, they like the community spirit and the fact that they are close to shops, schools, buses, doctors etc.

- Some residents even tend their own bits of garden and plant bulbs and flowers for all to enjoy, hence the fine display of daffodils and crocus each spring.

- In previous years we have won awards for our gardens and in 2012 we won two different 1st places at Petersham Horticultural Society show with displays of our roses and hydrangeas from the gardens. The awards were The Cowen Memorial Challenge Bowl and the Lambert Memorial Bowl

- And then we have problems that are not seen on the outside but are of course a constant distress to all concerned. Damp/condensation and mould.

- All three cause ill health in the young and old. Some residents have dehumidifiers on all winter long to keep the problem at bay.

- But what it really means is that our homes in Ham Close are no longer fit for purpose.

- They certainly would not pass any building regulations now, and are definitely not environmentally friendly.

- And they are far from friendly to new mums having to heave push chairs, babies and shopping upstairs or risk leaving the push chair in an open space free for cats or foxes to visit or for it to be stolen.

- And when we get past all our problems, we find we have more and most annoyingly, not of our own making.

- An increasing amount of Ham Residents seem to think that Ham Close is their dumping ground, from soiled nappies, beds, mattresses, all kinds of furniture and cars.

- Graffiti has been another problem but since we began looking after our gardens we have not had any graffiti in the actual blocks although it is still evident just outside the estate and still looks awful. When will they learn to spell?

- The latest trend seems to be to use Ham Close as a rat run from Ashburnham Road to Woodville Road, doing handbrake turns in the car parks and showering the cars with dirt and stones.

- But in spite of all this, I for one would rather live in Ham than anywhere else. We have fabulous walks, amazing local history, stunning parks and our community. What we need is respect. At the moment Ham Close is a cut through for just about everyone, the drug dealers stick out like a sore thumb, apparently this is not a massive problem in Ham, unfortunately when you live with it daily, it is just that.

- As Ham Close Residents we are sick of our estate being taken over by these arrogant bullies.

- We need to let people know that their disgusting habits will not be tolerated and that we are not a dumping ground nor are we a free for all for drug dealers and their kind.

- And for all that, you could walk on Ham Close Estate any time day or night and not have a problem.

- Ham Close is our home, it is where we live, it is where we make friends and memories, it is where we raise our children, it is where our children may raise their children and make friends and memories and it is where we may get old.

- We need an estate that we can be proud of, we need to make our estate a caring community and be there for each other. We need damp and mould free homes to protect all from illness like asthma. We need better, healthier living accommodation with safe areas for our children to play and enjoy being alive and growing up in a wonderful area, we need this estate to be an estate for the future for all.

Let me say from the outset and clearly that I am not denying Ms. Jenkins’ testimony. The list of complaints about the state of disrepair of the estate will be familiar to anyone who lives on a housing estate targeted for regeneration. The managed decline of residents’ homes is the single most persuasive means to get them to agree to their demolition, and consultancies are adept at identifying these as justification for the redevelopment of an entire estate. What I am denying, however, is whether the options Ms. Jenkins and everyone else on Ham Close have been given by Richmond Housing Partnership and its consultants, and especially by BPTW Partnership, to address these legitimate concerns are the only solutions. Above all, we refute that any of these complaints constitute legitimate reasons for the demolition of Ham Close estate, when each and every one of them can be remedied through a programme of refurbishment and maintenance by her landlord, RHP, and adherence by Richmond council to their civic duties as the local authority.

We presume that Ms. Jenkins is not an architect, and the conclusions she draws from the existing failings (that the homes at Ham Close are ‘no longer fit for purpose’, that they ‘would not pass any building regulations now’, and that they are ‘definitely not environmentally friendly’) have therefore been conveyed to her by the consultants. Every estate community ASH has ever worked with has at least one resident, usually vulnerable due to age or disability or both, sometimes on the board of the Residents Association, on whom the council, housing association or consultants focus their attentions, and whose repetition of such false conclusions they elevate to a mandate from the community to demolish and redevelop all residents’ homes. As we saw in Part 1 of this case study, such a mandate, or anything like it, did not exist when the Prince’s Foundation produced its report in October 2014; and while legitimate as an expression of her personal experience, Ms. Jenkins’ testimony here does not constitute the ‘majority’ she claims in her comment on ASH’s website who supposedly want the redevelopment to go ahead.

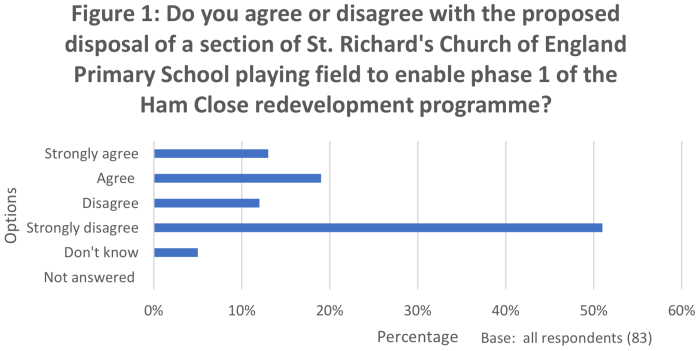

Indeed, in yet another consultation report, Future of Ham Close, published by BMG Research in March 2017, of the 305 respondents to the survey (84 tenants, 31 leaseholders and 190 respondents from the wider community), a full 50 per cent said they disagreed that the redevelopment of Ham Close would benefit them, and only 27 per cent agreed it would. Even when the question was narrowed down to ask if it would benefit the current residents of Ham Close, agreement only increased to 40 per cent, with 34 per cent disagreeing and 27 per cent undecided.

Most importantly of all, as the response to my questions from Charles Murphy, the Senior Project Officer at Richmond Council confirms, until RHP acquires a private development partner, no financial viability assessment of the redevelopment can be produced. As I wrote in Part 1 of this study, this means the breakdown of tenure types, rent levels, affordable housing quotas, shared ownership schemes and market sale properties given in the consultation document October 2016 is nothing more than speculation and promises offered to manufacture resident consent for a scheme about which they have none of the information required to give their informed consent. If a resident mandate for demolition has been manufactured by consultants since 2017, therefore, it has been based on nothing more than promises that neither RHP nor the council has any contractual obligation to honour. Of course, as Mr. Murphy also confirms, since RHP had a funding contract with the London Mayor signed prior to his policy on balloting residents of estates targeted for regeneration, the residents of Ham Close will not be given a vote on the future of their homes.

As I have pointed out throughout this case study, although the Prince’s Foundation claims to have considered a ‘refurbishment and partial redevelopment’ option (although not one that doesn’t include the unnecessary demolition of 5 of the estate’s 14 residential blocks), they have not produced a feasibility study of this by an architectural practice, or a viability assessment by a quantity surveyor of its costs compared to that for the full demolition and redevelopment of the estate. A refurbishment and infill development scheme, therefore, cannot have been offered as a genuine option to residents of Ham Close estate. So declaring, as Charles Murphy does, that refurbishment is ‘unaffordable’ is incorrect and misleading.

On the five estates for which ASH has produced such an option without the demolition of residents’ homes, three of which we have developed up to feasibility study stage, financial viability assessments of our proposals by quantity surveyors for the West Kensington, Gibbs Green and Central Hill estates have shown that refurbishment combined with infill development is not only affordable, but many times less expensive than the option to demolish and redevelop hundreds of structurally sound, reinforced concrete homes. Our own studies have shown that, because of the costs of demolishing and redeveloping the existing homes, their replacements will have to be at least 50 per cent properties for market sale, around 25 per cent properties for shared ownership and market rent, and 25 per cent homes for the various levels of affordable rent, all of which are considerably higher than social rent. These are the financial realities of the costs of estate redevelopment, which no amount of promises to residents can or will circumvent.

But in fact, the reason the Prince’s Foundation has given for dismissing the ‘refurbishment and partial redevelopment’ of Ham Close is not because of its cost, about which its Vision for the Future of Ham Close says nothing, but because it ‘does little to explicitly improve the village feel of the area’ and ‘does not integrate [the estate] more explicitly with the wider Ham context’. I hope Part 2 of this case study has shown how lacking in factual basis, ideologically motivated and deliberately misleading these statements are.

In addition, the Equality Impact and Needs Analysis to which the Senior Project Officer at Richmond council refers Councillor Andree Frieze is not included on the Ham Close Uplift website, where one would expect it to be, and is also not included in the Cabinet Report of November 2015 to which he directs her, which is the only cabinet meeting of that month. This is typical of the lack of transparency at best, and at worst deliberate disinformation with which estate demolition schemes are hidden from public scrutiny. But even if it does exist and was available, such equality impact assessments, as ASH knows from those we have read, are woefully inadequate tick-box exercises that don’t begin to address the full impact on residents and neighbours of the demolition and redevelopment of an estate such as Ham Close. Based as it would be on Section 149 of the Equality Act 2010 (public sector equality duty), the analysis would be limited to whether the new development discriminates against residents on the basis on their age, disability, gender reassignment, pregnancy, maternity, race, religion, sex or sexual orientation, and say nothing about whether they will be able to afford to return to the new properties. Nor will it address the environmental costs of the demolition of an estate of 192 reinforced concrete homes and development of an estate of 450 properties, and most particularly to the health of the children who will study and play in the adjacent infant and primary schools through the next 5-10 years or longer of the project. Significantly, in this respect, RHP’s phasing strategy does not include a timeline for the project. But then, how could they, when they haven’t even acquired a development partner to finance the scheme? Yet it’s on this absence of information that RHP’s consultants are claiming a mandate to demolish the estate.

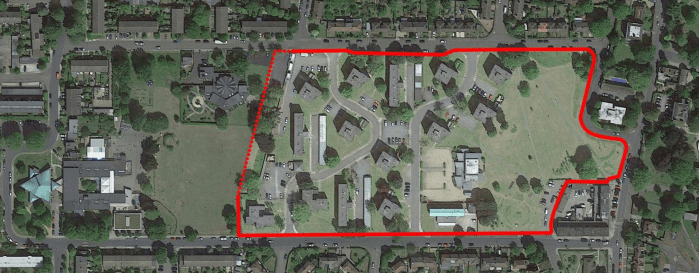

Finally, even within the flawed and unnecessary option to demolish Ham Close, it is extraordinary that Richmond council has given RHP the considerable strip of land to the immediate west of the estate (above) that is currently used by St. Richards and St. Andrews Primary School and Ham Infants School, on the completely spurious grounds that RHP needs this land if they are to build the first phase of the redevelopment without having to move existing residents out of their homes. To the very obvious alternative of the land currently occupied by the Ham Youth Club, Richmond council has responded that:

‘Given the constraints of the proposed Ham Close redevelopment, including previous messages to protect the green, there are no other open areas of land neighbouring the Close that are large enough to deliver the first phase of development.’

In architectural terms this is nonsense. Even if we were to accept the unfounded argument that it is necessary to demolish the existing estate in order to increase its housing capacity, the only constraints to using the land cleared of the demolished Youth Club for the first phase of such redevelopment is that this area is bordering Ham Green, and is clearly going to be where the high-value, market-sale properties envisioned by BPTW Partnership will be built, not the segregated affordable housing blocks to which existing residents will be moved. Across the UK school playing fields are being lost to private developers, with 215 sold in England since 2010, and Richmond council’s transferral of this public land and education and health amenity into the hands of private investors on such a flawed basis, and against the wishes of even the hopelessly unrepresentative survey (83 respondents) of the local community and parents of the school children (below), is nothing less than an act of privatisation designed to increase the profits of RHP and its development partners.

In the absence of a feasibility study and viability assessment of a refurbishment and infill option without demolition, and an impact assessment of its social, financial and environmental benefits compared to the enormous costs of a demolition and redevelopment option, the residents of Ham Close have not been offered what ASH has demonstrated to be the most the financially viable, socially beneficial and environmentally sustainable option available to them. Given the choice residents of Ham Close have instead been fobbed off with between the continued managed decline of their homes and their demolition and redevelopment, we can understand why some residents, like Ms. Jenkins, have chosen the latter. But this is not the only choice. Most importantly, the consequences of following the latter option, as the dozens of estate demolition schemes across London irrefutably demonstrate, will have serious and potentially prohibitive consequences for residents’ financial ability to remain on the Ham Close estate they have made their home, and in which they deserve to continue living in well maintained and renovated social housing for many years to come.

Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and after more than four years of work we still have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

One thought on “The Regeneration of Ham Close Estate. Part 2: For a Socialist Architecture”