‘I have spoken of the operation of a certain type of fashionable photography that makes misery into a consumer good. When I turn to the New Objectivity as a literary movement, I must go a step further and say that it has made the struggle against poverty into a consumer product. In fact, in many cases its political meaning has been exhausted with the transposition of revolutionary impulses – insofar as these appeared among the bourgeoisie – into objects of distraction and amusement that were integrated, without difficulty, into the entertainment industries of the big cities. The metamorphosis of the political struggle from a drive to make a political commitment into an object of contemplative pleasure, from a means of production into an object of consumption, is the defining characteristic of this literature.’

– Walter Benjamin, The Author as Producer (1934)

1. The Art of Catharsis

Who profits from the housing crisis? The immediate answer is obvious: property developers, housing associations, estate agents, consultants, architects, builders, the people who knock down council housing and replace it with new-build properties, half of which currently stand empty in London.

But there are other people who profit too. First in line, spotting a market in sob-stories for the middle classes, are the journalists, whose thin prose and even thinner research doesn’t stop them from bundling a few articles together and calling it a book. Behind them, ponderous as ever but champing at the bit of the next government grant, are the academics, who have responded to the burgeoning market in well-footnoted (to other academics), badly framed (‘gentrification’) and totally apolitical books about the housing crisis, which they transform into just another object in their musty archive.

But a new profiteer has emerged. As the public’s interest even in the fluff on the bookshelves wanes, enter the artist. In verbatim theatre productions, in performance poetry, in documentary films, in protest songs and in books of glossy photographs, the artist is the new self-appointed spokesperson for the masses, and their great claim to this role is – not the political and representational agency of their work – but something much more important: their sincerity.

The English have a strong claim to being the most artistically illiterate nation in Europe, and generally prefer a nice swing at Tate Modern to anything that makes them think. But this week, thinking about the latest piece of artistic ‘activism’ to come off the shelves, full of sincerity and endorsements from every hack, academic and luvvie in town, I was reminded of what the German critic, Walter Benjamin, said about fascism in his 1936 essay The Work of Art in the Age of its Mechanical Reproduction. Fascism, remember, was a kitsch, saccharine aesthetic that sugar-coated the violence it glorified for the masses in images of noble sacrifice; and it has more than a few parallels with the photographs of homeless Britains, protesting Palestinians and starving Yemenis that decorate our Sunday supplements or perch in glossy tomes atop many an Islington coffee table. Trying to understand this aestheticisation of the violence of the political, Benjamin concluded: ‘Mankind’s self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order.’

Poverty porn is nothing new, and has been the staple of reality TV for some time, preparing the way for the political assault on the working class it has served. Somewhat belatedly, the liberals who have colonised the arts in this country have now come up with their own use for the working class. Springing from the Methodism that defines the aesthetic and political sensibilities of the so-called Left in this country, this goes something along the lines of: ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ In the political vacuum of liberalism, art is the opium of the middle classes, its aesthetic pleasures the last refuge from their willing embrace of the violence of capitalism.

It’s not by chance that the favoured, most sought after and most highly valued aesthetic response of the middle classes is tears. Tears stop the middle-class film-goer from seeing what’s in front of his face when he leaves the auditorium. Tears, whatever the middle-class book-buyer may think when leafing through its moving photographs, are always shed for herself. And the feel of tears running down their cheeks, the salty taste of them in their mouths, makes them feel that somehow they are sharing in the suffering they tell as many people as possible is their cause. Identification (preferably with a distant and grateful victim) is the cathartic object of the immersive art ‘experience’. ‘Heartbreaking!’ is the ultimate accolade for the liberal work of art. So what role does art play for its liberal audience in search of catharsis?

2. Lamentations of the Liberal

Last week someone told us that a photograph of Cotton Gardens estate was reproduced as a centre spread in the current issue of The Big Issue. It’s a long time since I’ve bought a copy of this paper, which is sold for free by homeless vendors, but I remember that last year, shortly after the Grenfell Tower fire, its founder, Lord John Bird, described Lancaster West (to which Grenfell Tower belonged), as ‘that terrible estate’, and said he liked Margaret Thatcher’s Right to Buy policy because it gave the working class a chance to ‘own their own property’, just like the middle classes, and thereby have access to ‘social mobility’. He said a lot of good stuff too, about nationalising government-owned land and using it to build social housing; but you have to wonder whether, from his velvet-lined seat in the House of Lords, Lord Bird is aware of the damage his words do to the image of the council estates local authorities, the London Mayor and the Government are so intent on demolishing.

The photograph is by Alessia Gammarota, a photographer with an eye for both architectural and social relationships, who has worked with ASH before on our ICA show, and was taken from the balcony of our home in Cotton Gardens estate in Lambeth. The reason it has been reproduced in The Big Issue is that it appears in Paul Sng’s book, Invisible Britain, which was published last week hard on the accolades for his 2017 film Dispossession: The Great Social Housing Swindle. There’s an aesthetic sensibility – call it middle class, call it liberal – that can’t help but see council estates as ‘gritty’ and ‘edgy’, as somehow more authentic than, say, a Brighton townhouse, that sees them (when it has brushed the tears from its eyes) through the lens of a clichéd tradition of photo-journalism that views the working class as objects of middle-class charity, as testimonies to the failures of this or that Tory policy, and, above all, as the ‘heartwarming’, ‘haunting’ (etc) subject of their latest book, film, poem or other work of art – never as places of community, never as resistant to their outsiders’ gaze, and never, ever, as sites of opposition, resistance and organisation. Like Lord Bird, what these largely terrace-dwelling artists need to learn is that every negative comment or image they make under the apparently overwhelming compulsion to express their sensitive souls is another wrecking ball in the argument for the demolition of the council estates in which the working class live.

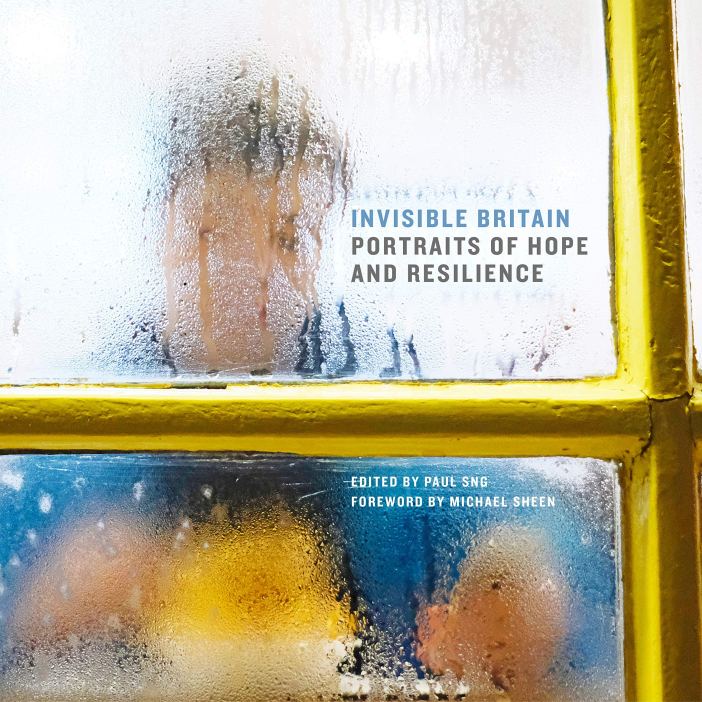

The cover of Paul’s book – showing a rain-spattered window whose droplets presumably stand in for the tears I would guess the photographs inside are meant to bring gushing forth – wasn’t promising. But I hoped the inside would contain more than the lamentations for the loss of social housing that defined Paul’s informative but apolitical film, and that the captions were more factual than the one that accompanies this photo in The Big Issue. For in fact – rather than in the universal denigration of council estates by people who have never lived in one – according to a FOI request of 2012 only 38 of the homes in Cotton Gardens estate were leasehold compared to 200 tenant households, so about 15 per cent, which is pretty low for an Inner London estate. And in fact – although the repairs, outsourced by Lambeth council to private contractor T Brown Group, would be better carried out by a blind baboon – the estate is not, as the caption to this photograph says, ‘neglected’, but in pretty good nick. And in fact – rather than standing on the other side of weeping window panes taking moody photographs – ASH is currently organising a collective project designed to celebrate both the architecture and the community of Cotton Gardens estate.

I know that facts tend to go astray when the artistic temperament kicks in – especially when pound signs are dangled in front of your face by a bunch of well-connected luvvies – but it’s indicative of their intentions that neither Lord Bird nor Paul Sng – the latter of whom who has stood on our balcony many times drinking our booze and smoking our fags – contacted us first to ask about the estate before using it to illustrate the claim, in the caption, that ‘many of the city’s social housing units – such as the Cotton Gardens estate in Kennington (foreground) – have been neglected or sold.’ Alessia’s photograph, which juxtaposes the towers of encroaching capital with the towers of council housing, captures some of the extraordinary design features that have helped to make Cotton Gardens estate such a strong and successful community; but context is everything in our visually illiterate society.

But this is about more than the separation of Lord Bird and a bunch of artists from the world they’ve elected themselves to represent; it’s also about compensation. Paul Sng, as he likes to remind people, was born on a council estate in Deptford; but now he lives in a tastefully appointed Georgian townhouse in Brighton. There’s nothing wrong with that, but liberal lamentations always spring from middle-class guilt, and the people Paul has surrounded himself with professionally – Maxine Peak, the actor who narrated Dispossession; Luke Doonan, the property developer who financed it; and Lynsey Hanley, the academic who reviewed it – are all working-class kids ‘done good’; and they are all, also, converts to the Church of St. Corbyn whose answer to all our woes is: ‘Vote Labour!’

Part of becoming middle-class is the guilt inherited from leaving the class into which you or your parents were born. But as a fully paid up member of the middle class, working in its professional milieu, enjoying its material comforts and with access to its contacts in the art world and media, that guilt overwhelmingly finds expression these days in liberal tears: in the cult of personality that has sprung up around the wobbling head of Oh Jeremy Corbyn, in cinematic weepies like Ken Loach’s I, Daniel Blake, and in photographic weepies like Paul Sng’s Invisible Britain. As Michael Sheen – an actor I otherwise like – writes in the book’s Foreword: ‘There are things in these stories that are shocking. Things that have moved me to tears.’ Well, yes, but how is telling us that in a book of conventional photographic portraits going to help in organising working class political action against those things? That, of course – as the working-class academic and activist Lisa Mckenzie has pointed out in her ethnographic studies of the English class system – would mean questioning your own class position within the art and academic worlds you now inhabit. Although I personally appear quite a bit in Dispossession (or at least I used to: I wouldn’t be surprised if Paul has cut me out!), he refused to include the work of ASH and the design solutions we have developed to the housing crisis the rest of the film spends 90 minutes hours bemoaning. ‘That’s not the kind of film I want to make’, Paul told me when I suggested he devote even 5 minutes of his film to ASH’s design alternatives to the estate demolition programme whose social effects he was documenting. I guess that’s not the kind of book he wants to make either. So what is the purpose of Invisible Britain?

3. Invisible Labour

On Saturday, after an afternoon being shown around the Carpenters estate by residents fighting to resist its demolition by Newham Labour council, we walked into Foyles on the Charing Cross Road to have a look at Paul’s book. Ironically, there was a Big Issue seller standing outside in the rain, and we bought a copy. I found Paul’s book, appropriately, in the ‘Art’ section, and looking around for a seat finally found a stool in front of a new section upstairs marked ‘Activism’. Now I’ve had a chance to look through Invisible Britain, I can honestly say it’s even worse than I feared. The interviews come straight from the Guardian school of bleeding-heart journalism for the middle classes, and its photographs, many of which I’d seen online, are by turns sentimental and voyeuristic, and the sort of ‘dignity of suffering’ guff you’d see in any Sunday broadsheet on that weekend’s latest ‘crisis’. Most disappointing was that, despite Paul writing in the Introduction that he wants ‘to enable people from disadvantaged backgrounds to tell their own stories’, every single photograph in the book is by a professional photographer. I guess Paul didn’t trust the people to whom his book is supposedly ‘giving’ a voice to ‘take’ their own photographs, even in the age of the selfie; but his reference to ‘disadvantaged backgrounds’ speaks volumes about the company he’s keeping. Because despite its complete lack of any reference to any form of working-class political agency – which is limited to staring back at the camera lens in various postures of defiance – this coffee-table book most definitely has a politics.

Eight of the interviewees are from London, and of these half talk about the experience of living on a council estate. Jasmin Parsons talks about her experience of organising resistance to the demolition of the West Hendon estate in Brent; Demelza Toy Toy talks about living on the World’s End estate in Chelsea surrounded by some of the richest people in the UK; and Corinne Jones is a survivor of the Grenfell Tower fire in Kensington and Chelsea. The fourth interviewee is Nadine Davis, who lives in Hackney, and talks about the attempts to move her off her estate. However, her estate isn’t identified. Nor are the only two photographs of council estates in the book, both by Alessia Gammarota, one of which shows the Aylesbury estate in Southwark, the other of Cotton Gardens estate in Lambeth. Why? Is it just coincidence that the three London estates Paul has chosen to identify in his book are all in Conservative-run boroughs, even though London is overwhelmingly a Labour-run city, with 21 Labour councils compared to 7 Conservative, and where – of more relevance to estate residents – 195 estates are being regenerated, demolished or privatised by Labour-run councils compared to 35 by Conservative councils?

Last year I wondered whether Oh Jeremy Corbyn agreeing to come to a screening of Dispossession and answer questions by residents whose estates are threatened by Labour councils signalled the beginning of the campaign by the Labour Party to appropriate Paul’s film to its own ends. But this book, captioned with as many endorsements from some of Corbyn’s most one-eyed supporters (Ken Loach, Aditya Chakraborrty, Michael Sheen) as it is well-deserved denunciations of the Conservative Government of Theresa May, shows that I needn’t have worried. You don’t have to co-opt someone who has leaped into your arms. Invisible Britain isn’t just liberal rubbish artistically – directed shamelessly at the Christmas market in middle-class catharsis for £20 a pop – but politically it’s little more than propaganda for the Labour Party. Indeed, among the panting accolades for it on Amazon’s website – ‘haunting’, ‘brilliant’, ‘tender’, ‘stunning’, ‘moving’, ‘powerful’ and (yes) ‘heartbreaking’ – is one by none other than the Right Honourable Jeremy Corbyn himself:

‘One of the most shameful legacies of this Government will be the way in which it gave rise to a nasty culture of stigmatising working class communities and looking down on those just struggling to survive, who could be any one of us in different circumstances. These stereotypes don’t just demonise some of Britain’s most deprived communities, they are actively used to justify and excuse the damaging policies that are making people’s lives worse. This book powerfully gives voice to the experiences and perspectives of people who we are used to being marginalised and silenced.’

Thanks for that, Jezza, but speaking of damaging policies and the stigmatising of working-class communities used to justify them, you should check out your own party’s policies on housing and how they’re being implemented by Labour councils contemptuous of the voices of residents and constituents. This shows, once again, how amenable weak images are – and despite their worthy intentions these photographs are surprisingly weak – to political co-option. Corbyn’s tell-tale reference to those ‘who could be any one of us’ is the very model of liberal catharsis through the fantasy of identification. The ‘moving’ portrait of the ‘marginalised’ other is the oldest cliché of documentary photography, the politics of which are as dubious when applied to a starving Ethiopian as to a homeless Briton. Unfortunately, the critiques of this tradition of representation seem to have been forgotten or never known or simply discarded by the creators of the emotive, unreflexive, voyeuristic and sentimental framework through which these photographs invite us to view their subjects. The same thing that has happened to the self-representing, self-organising, self-politicising council residents of 2015 who ended up, two Saturdays ago, standing outside an empty City Hall listening to speeches by pro-Labour groups about how Jeremy Corbyn will save them, has happened to the representation of the struggle for social housing. Just as every Goldsmiths student in a hoodie is now an anarchist and every actor an activist, so the hope of political organisation by the working class outside the suffocating grasp of the Labour Party has faded into the bleeding-heart liberalism of Invisible Britain. I can see this glossy volume sitting proudly and slightly too conspicuously on the coffee tables of Islington and Brighton, but it won’t be on ASH’s Christmas list. As Bob Dylan once sang: ‘Now ain’t the time for your tears.’

4. Visible Action

So what would a political – as opposed to a cathartic – art look like? Well, it’s ironic that the only two photographs in Invisible Britain that are not of people are by Alessia Gammarota, as she has documented several of the meetings and workshops ASH has had with residents, and her photographs don’t show individuals staring back at the camera in the mere pose of defiance, but as collectively fighting for their homes and communities, as actively engaged in organising the resistance that is completely absent from Invisible Britain: Portraits of Hope and Resilience. ‘Hope’, one of Jeremy Corbyn’s favourite words, is the opium of the Labour-voting classes, not a housing policy. ‘Resilience’ is a Puritan value, not a plan of political action. But then Liberalism likes the objects of its sympathy to be immobile, passive, isolated, weak, needy and grateful, everything the people in Alessia’s photographs are not. These photographs – showing residents on the Patmore estate in Conservative-run Wandsworth, of the Northwold estate in Labour-run Hackney, and the squatters who occupied an empty building in Poland Street in Conservative-run Westminster – and the working-class agency they document and make visible, are the antithesis of the politics of representation in Invisible Britain.

Simon Elmer

Architects for Social Housing

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we have received minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

Reblogged this on Wessex Solidarity.

LikeLike