‘At issue is an entire conception of the destinies of human society from a perspective that, in many ways, seems to have adopted the apocalyptic idea of the end of the world from religions whose suns are now setting. Having replaced politics, even the economy, in order to govern, must now be integrated with the new paradigm of biosecurity, to which all other needs will have to be sacrificed.’

— Giorgio Agamben, Biosecurity and Politics (11 May, 2020)

Table of Contents

- Four Anecdotes

- Two Metaphors

- Unexplained Deaths

- Causes of Excess Deaths

- Collateral Damage

- The Worst-case Scenario

- Comparative Government Responses

- Alternatives to Lockdown

- Spreading Inequality

- Outsourcing the State

- The Security Ratchet

- Manufacturing Compliance

One of the things to have been revealed by the crisis caused by the global response to the coronavirus is that the overwhelming majority of people, and certainly in liberal democracies, would rather believe a lie to which we’ve been told how to react — in this case a civilisation-threatening viral pandemic that can be combatted through standing two metres apart, increasing the powers of police to arrest us and biometrically tracking our every move — than believe a truth to which we don’t have a clue how to respond. Confronted with the accelerated totalitarianisation of the UK being implemented under a de facto State of Emergency, we have chosen to listen to the lies of the Government and its media telling us exactly what to do and for how long, rather than hear a truth on which we will have to think and act for ourselves.

If you’re one of the former, as 99.9 per cent of people in the UK appear to be, then you won’t have read even his far, and will most likely have already dismissed me as a ‘coronavirus denier’ — that new favoured safe-word of liberals. But if you’re one of the 0.1 per cent that is still thinking, questioning and interested in resisting, this article is an attempt to estimate the collateral damage caused by the so-called ‘lockdown’ of the UK imposed by the Government on 23 March, 2020. In little more than two months, this decision, which has been enacted with varying degrees of severity by nearly 150 countries around the world, has changed the country we lived in for the foreseeable future. My last two articles looked at, respectively, the manufacturing of consensus for this decision and the regulations, legislation and deals made by the Government with this consensus. This article, my ninth on the coronavirus crisis, will look at the ongoing costs of this decision, which has been made not only by the Government of the UK but by us, its people, who have acquiesced without question or protest to every measure imposed upon us. Part of that acquiescence has been our collective refusal to look at the collateral costs of the lockdown, both now and in the future. This article is my contribution to beginning that act of looking.

1. Four Anecdotes

I want to start with some anecdotes. I wouldn’t usually when discussing a nationwide, and indeed worldwide, pandemic; but anecdote has been raised to the status of holy writ in the debates about the actions of the UK Government in response to the coronavirus crisis. Logic of argument, citation of facts, proof of statistics, authority of sources: all fall before the mighty weight of personal anecdote. ‘Tell that to the families of the dead’, runs the often-repeated rejoinder to the incontrovertible fact that COVID-19 is a threat almost exclusively to those over 65 years of age with one or more pre-existing chronic illnesses, as if the writer had personal access to the feelings of everyone in the UK who knows someone that has died. ‘My sister is a nurse, and she’s been traumatised by this experience . . . ’ begins the response to the information that, far from being overwhelmed by the vast numbers of COVID-19 deaths during this unprecedented epidemic, our hospitals are in fact empty. And the newly-knighted (but still underpaid) heroes of our ‘frontline’ in this war against an invisible enemy haven’t been shy about coming forward. ‘I woke from sleep after my night-shift to find the beaches and parks filled with people. Why do I bother?’ comes the plaintive cry, retweeted thousands of times over, of any number of medical practitioners turned social media gurus. All it has taken to justify the latest regulation, a new measure, the turning of a guidance into an instruction, or the roll-out of a biosecurity system out of the dystopian nightmares of our future, is the report of the death of a single mini-cab driver, bus driver, construction worker, cleaner or other (until very recently) unskilled worker uncritically and unquestioningly attributed to ‘COVID-19’. So before I move into more reasoned arguments, let me begin with a few personal anecdotes of my own. All are about people I know personally, but to protect their identities I won’t reveal here either how I know them or their real names.

P. owns and works in a Chinese take-away restaurant. He’s in his late 70s, has a background in construction and is on his feet most of the day, so looks fit for his age. Before the coronavirus crisis he had been waiting over a year for an operation there was a small percentage chance that he wouldn’t survive. He had recently been contacted by the hospital at the last minute and offered a brief window of opportunity, but at such short notice he declined. The last time I asked him about whether he’d heard something he placed his heavy hand on mine and gently told me he wished everyone would stop asking him, as it was making the waiting worse. I swore I wouldn’t ask him again. When the virus officially reached these shores, he told me that he intended to keep on working as usual, and that a positive frame of mind was key to good health. The next time I went for a takeaway P. had some news. He’d gone in for a preliminary check-up, and the hospital had discovered he had cancer. It was so advanced that he was operated on within 24 hours, had been in bed for a week, but was now looking surprisingly hale. I saw him once more in the pub after that, and the news was good: it looked like they’d caught the cancer in time. The following week social distancing was enforced, and shortly after that the lockdown of the UK was imposed. The restaurant is still serving takeaway, and every time I go I ask after P. He’s well, but, as someone of his age who has recently had an operation, he is quite reasonably in quarantine. He’s an independent man, and after a day on his feet likes a late-night pint. I can imagine how being locked inside is making him feel, but he’s one of the lucky ones. He has family around him to keep his spirits up, and, even more fortunately, the operation that saved his life was conducted the week before the NHS began to prepare for COVID-19. If it wasn’t, would he have been invited into the hospital for a check-up? If he had been, would he have gone with all the fearmongering in the media? And if he was invited and had gone and they had found the cancer, would they have performed the operation?

The second anecdote is about R. A retired barrister, he too is in his late 70s, but has a history of respiratory disease. Unlike P., he lives on his own in a private housing estate. That means the one bench in the estate’s communal garden hasn’t been covered with tape by the council, but fear has been enough to keep his neighbours from stopping for a chat. I have watched young women who share his entrance hall flee him like a leper in their haste to get inside their flats. Before social distancing, R had a social life composed of classical concerts, singing groups, and recently even the local church. Now that’s all gone. We visit him once a week, where we stand or sit outside his flat or in the communal garden, careful not to cough in his direction but otherwise behaving normally. But the real danger to him isn’t infection with the virus but the lockdown itself. Maybe 6 months before the coronavirus crisis reached the UK, R. began to show the first signs of dementia. A juggler of words with a dry sense of humour, he began to struggle to find the right one. While his memory of the past remained extraordinary (on the cusp of social distancing we spent an evening with him recalling past legal cases from the 1970s), he has recently and rapidly declined into more than memory loss. I say dementia, but it could also be Alzheimer’s disease, or even be the result of head trauma. Before lockdown, he too had been waiting for an appointment: not for an operation, but to assess the cause of his memory loss and, through that assessment, to qualify for some form of home care and, possibly, care home. Although he goes for long walks in the middle of the night when the police won’t stop him, living alone in his apartment and seeing maybe two people a week for an hour at a time, has rapidly accelerated his inability to function. The array of technology and gadgets that allow us not only to stay in touch with the outside world and our friends but also to live alone have turned into an incomprehensible puzzle for him. We advised him to stop using social media, which was increasing his anxiety. His laptop and phone have become a malign gremlin in his home. Now he no longer knows how to use the oven. He needs either home care to visit him or to move into a care home. But seeing R. on a weekly basis over the past few months, it is clear that his condition has been worsened and accelerated by the lockdown.

My third anecdote is about M., whom I know less well. I’d guess in his mid-40s, he and his wife run an Italian restaurant. For the past five years they’ve worked hard to build a clientele for authentic Italian dishes in an area where takeaway pizza is the more usual association with their country’s cuisine. Their spaghetti al nero is a thing of delectation. As COVID-19 was scything through the disproportionately elderly population of Italy, we visited their restaurant. The local vicar sat at one end of the room, M. at the other. He looked worried, not only by the stories of what was happening in his homeland printed in lurid detail on the front covers of our press, but at the thought of what would happen to his business when the virus reached the UK. Since the lockdown started they too have been providing takeaway food. The squid ink pasta is off the menu, but we have done our best to support them financally, not only by ordering takeaway meals but also buying our pasta from their dwindling stock. But the last time we met, M.’s wife told us they are broke. All their savings from five years of work have gone keeping the shop afloat during the imposed suspension of trading under lockdown. Now they will have to sell up for what they can get and return to Italy. She was furious, and wasn’t shy about expressing her view that the whole coronavirus crisis had been grossly exaggerated, both in Italy and in the UK. My neighbourhood will be much the poorer for their departure.

My fourth and last anecdote is about D. In his late-20s, D. works as a forklift driver in Derby for Holland and Barrett, the UK health-food retailer that three years ago was purchased for £1.8 billion by Russian Billionaire Mikhail Fridman. When social distancing came into effect, D. was told H&B are an essential business and he continued to work in the company’s warehouses, in close proximity to his fellow workers. When the lockdown of the UK’s businesses was announced, Holland and Barrett was exempt and D. was not offered furlough. Instead, workers from a local warehouse that was closed down were drafted in, increasing the density of workers. D. has a healthy suspicion of anything the Government tells us, but even he began to worry about his health under the barrage of daily scaremongering in the media. Then, a fortnight ago, an employee in Burton tested positive for SARs-Cov-2. In response, Holland and Barrett told the Derby Telegraph that all its staff had been tested, that social distancing is strictly enforced in the workplace, and that all workers have PPE. In reality, neither D. nor any of his fellow employees had been tested, and they only found out about the story on social media. D. made this point online in a comment on a Burton Mail post linked to the Telegraph article, and the next day he was sacked. As an agency worker with no unionisation, D. has no employment rights, so his only recourse now is to try to find new employment in a collapsing job market, without a recommendation from his previous employer, and most likely having been blacklisted in the industry — or to apply for Universal Credit. Even as a skilled forklift driver he made £8.82 per hour, so he has no savings, and is facing at least a month without pay, at the end of which he will have to find the money for his next month’s rent for his private landlord. Unsurprisingly, D.’s last Facebook post reported that his anxiety levels were ‘through the roof’.

2. Two Metaphors

These, and the millions like them, are the people I want to talk about in this article: the ‘collateral damage’, as the US Military likes to call its unintended victims, of what has from the very start been characterised and conducted in this country as a ‘war’ on the coronavirus epidemic, with its ‘frontline’ workers, its medical ‘heroes’, and the daily reports of the fallen dead. Like the victims of collateral damage, these will eventually far outnumber those who have died on the field of battle, for the real casualties of war take years after the battles have ended to accumulate their gruesome numbers. And like all collateral damage, the casualties are not limited to loss of life, but include the infrastructure of our society, from the small businesses struggling to survive the enforced suspension of trade to the national institutions — most obviously the NHS — whose privatisation is being accelerated and expanded under the cloak of this manufactured crisis. For just like every warzone, it is under the cloak of media lies and the protection of martial law, through terrorised civilians and a society in ruins, that the multi-national corporations funding the war enter with their irresistible plans to save a defeated people.

I owe it to Peter Hitchens, the Mail on Sunday columnist, for reminding me that the term ‘lockdown’, which has slipped so easily into our vocabulary, is a term used within the gulag of the US prison system to describe the confinement of inmates to their cells when there is a perceived risk of an uprising. Indeed — although Hitchens will not thank me for pointing it out — it is this solitary confinement that the UK Government has imposed on Julian Assange since his extra-legal incarceration and torture in Belmarsh Prison. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that the always obedient British poodle to the constantly barking US watchdog has so readily adopted this terminology for the emergency measures it has imposed on the UK public under the aegis of the coronavirus crisis.

There are two metaphors, then, that have been deployed to justify the suspension of our civil liberties, human rights and political agency for the foreseeable future: the prison metaphor, in which UK citizens have first been isolated from each other and, under the new Test and Trace programme, are now being subjected to a digital panopticism in order to avoid and monitor contagion; and the war metaphor, in which collateral damage from the lockdown has been justified as a necessary evil whose consideration, let alone publication, is bad for the ‘morale of the nation’, as our would-be Churchillian Prime Minister would no doubt argue. It’s a characteristic of contemporary warfare that it is conducted with an almost complete absence of scrutiny of its human and financial costs by the people in whose name it is being perpetrated and whose taxes pay for it, and the war on COVID-19 has been no different. That this is a civil war, waged against an invisible enemy whose host is ourselves, has only increased the opportunities for exaggerated figures, groundless analogies and fictitious narratives of threats to our biosecurity.

3. Unexplained Deaths

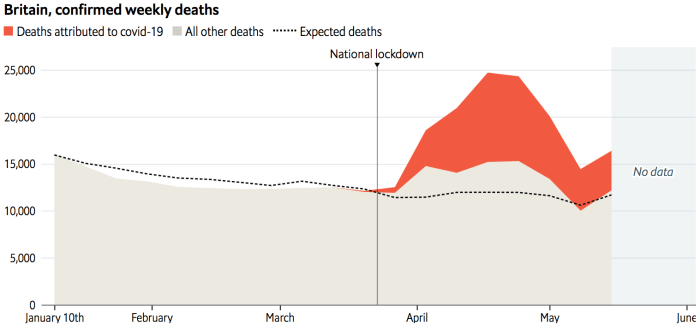

So let’s start with the most measurable effect of the lockdown. According to the Office for National Statistics, the 11th week of 2020, ending 13 March, was when the first deaths in England and Wales officially attributed to COVID-19 were registered. It was only in the following week, however, ending 20 March, that the total number of weekly deaths exceeded the average deaths for the corresponding week over the previous 5 years. It wasn’t the first time this had happened in 2020. In the first two weeks of the year, ending respectively on the 3rd and 10th of January, the 12,254 and 14,058 deaths exceeded the average for that week by 79 and 236, the latter due to the 2,477 deaths that week whose underlying cause was a respiratory disease, around 300 higher than the preceding or following week. From then, though, 2020 has been consistently lower in the overall deaths in England and Wales than the average for the preceding five years. This is not surprising, given the seasonal influenza epidemics of 2017-18, when there were 26,400 excess deaths attributed to influenza-related diseases in England alone, and of 2014-15, when there were over 28,300 excess deaths.

However, from week 12 of 2020, ending 20 March, to week 21, ending 22 May, the last for which we have data, the total weekly deaths in England and Wales has been consistently higher than the average over the previous 5 years. This doesn’t tell us that much, as in many weeks in 2015 and 2018 there was as high or a higher number of deaths than in all but the highest number of deaths between weeks 12 and 18 of 2020; but it does give us an average from which we can extrapolate so-called ‘excess deaths’. It has been on the number of overall deaths above this average that the ‘lockdown’ of the UK has been justified by the UK Government, so it seems fair to use the same measure to arrive at the number of excess deaths caused by that lockdown.

Between weeks 12 and 18 of 2020 there were a total of 118,990 deaths in England and Wales. This is 46,566 more than the average number of deaths in these seven weeks over the past five years. Of these excess deaths, 33,360 have been attributed to COVID-19; but this figure leaves 13,206 unexplained deaths in excess of the average for the same 7 weeks of this year. The following week, the 3,930 deaths attributed to COVID-19 outstripped the 3,081 excess deaths; but in the week after that, ending 15 May, the 3,810 deaths attributed to COVID-19 left 575 of the 4,385 excess deaths that week unexplained. In week 21 the excess deaths again fell below the deaths attributed to COVID-19; making a total of 13,781 unexplained deaths between weeks 12 and 21. This represents nearly 25 per cent of all 56,380 excess deaths in this 10-week period.

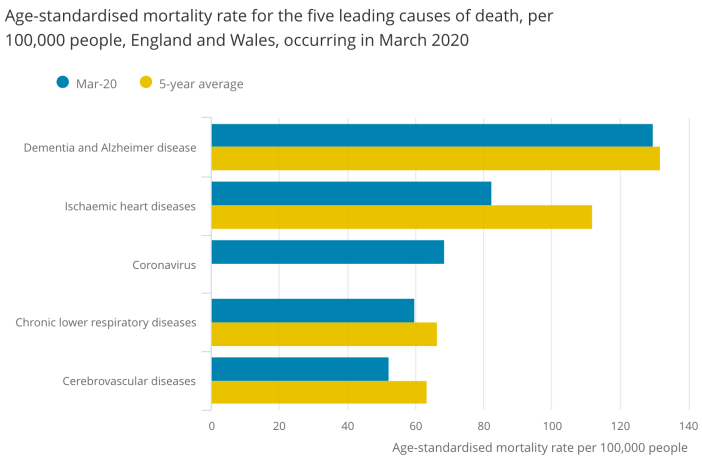

In reality, though, given the extraordinarily lax criteria for attributing a death to COVID-19, which I analysed in detail in Manufacturing Consensus: The Registering of COVID-19 Deaths in the UK, the actual number of excess deaths not caused by COVID-19 is undoubtedly far higher. Analysis by the Office for National Statistics has found that 14 per cent of death certificates ‘mentioning’ COVID-19 in March did not list the disease itself as the ‘underlying cause of death’. Not only that, but of the deaths that month in which COVID-19 was mentioned somewhere on the certificate, there was at least one pre-existing medical condition in 91 per cent of cases, with an average of 2.7 co-morbidities. These included influenza and pneumonia, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The most common of these pre-existing conditions, however, was ischaemic heart disease, which was listed as a co-morbidity on 14 per cent of deaths in which COVID-19 appeared on the death certificate. Significantly, the mortality rate from ischaemic heart disease — usually one of the biggest killers in the UK — was 29.5 per cent below the 5-year average for the month, and lower for the other leading causes of death, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, chronic lower respiratory disease and cerebrovascular disease. This could mean that COVID-19 accelerated the demise of some people who were already close to death, but it could also mean that some deaths from heart disease and other health conditions were being incorrectly attributed to COVID-19, as NHS doctors are finally coming forward to admit.

The only figure I’m aware of indicating what the actual number of deaths caused by COVID-19 might be is that calculated by Professor Walter Ricciardi, President of the Italian National Institute of Health and scientific adviser to the Italian Minister for Health. Back in March, following a re-evaluation of death certificates ‘mentioning’ COVID-19, he announced that only 12 per cent showed a direct causality from the coronavirus. If we were to extrapolate from this percentage and apply it to the 43,689 deaths attributed to COVID-19 between 20 March and 22 May, according to which only 5,242 would show a direct causality to the disease, the remaining 38,446 deaths, added to the 13,781 unexplained deaths over these 10 weeks, would push that figure up to 52,227 deaths in excess of the average for this period over the past five years, and which cannot be explained or do not have a direct causality from COVID-19.

To make such a calculation, of course, would be to make an over projection, and I’m certainly not claiming it as accurate; but it at least points towards the numbers we’re discussing when trying, in the absence of official figures, to estimate the collateral damage since the imposition of social distancing as Government guidance on 16 March and the official ‘lockdown’ of the UK on 23 March, the exact week when deaths in England and Wales began to rise above the average over the past five years. But whether it’s 52,227 excess deaths without direct causality from COVID-19 or 13,781 deaths unattributed to COVID-19, these deaths need to be accounted for, explained and justified with more than the easy dismissal as ‘collateral damage’ with which they have been largely buried by the UK media.

4. Causes of Excess Deaths

One attempt to try to explain these unexplained deaths, usefully summarised by Full Fact, has been to attribute them to deaths from COVID-19 in care homes or at the home of the deceased where, either because the doctor wasn’t certain or because a test for SARs-CoV-2 wasn’t available, the disease wasn’t mentioned on the death certificate. This has supported the claim, gleefully pounced upon by the fearmongers in the media, that the number of COVID-19 deaths is in fact far higher than the already exaggerated official total.

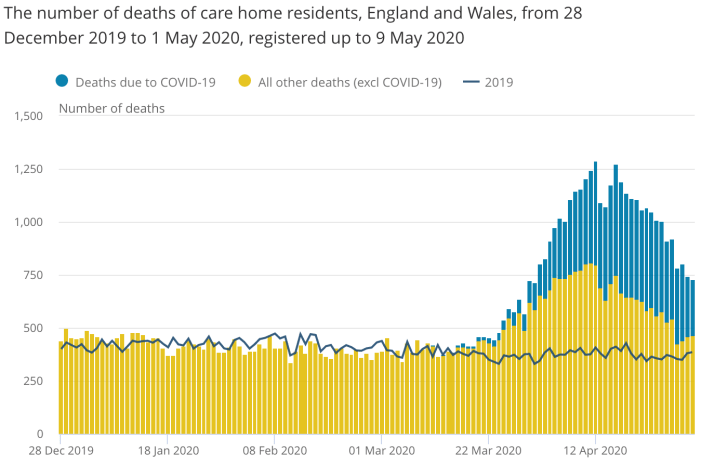

However, while this failure to identity possible cases of COVID-19 may have been the case up until 10 April, when the Office for National Statistics began including figures on ‘COVID-related deaths’ in care homes that require nothing more than a statement from the care home provider to the Care Quality Commission that they ‘suspect’ the ‘involvement’ of COVID-19 — whether or not this corresponds to a medical diagnosis or positive test for SARs-CoV-2 or is otherwise reflected in the death certification — it has not been in the weeks since. Moreover, if deaths in care homes accounted for the unexplained excess deaths, we would expect to see a sudden narrowing of this gap between excess deaths and deaths attributed to COVID-19 after 10 April. But in fact, while the previous week there had been a gap of 1,754 unexplained deaths, in the following week, ending 17 April, although the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 under the new rules rose from 6,242 to 8,791, the number of unexplained deaths rose to 3,063; in the week ending 24 April there was a gap of 3,298, and in the week ending 1 May there was a gap of 1,976. Only in the week after that, ending 8 May, did the deaths attributed to COVID-19 exceed the excess deaths; but the following week, ending 15 May, the gap had returned with 575 unexplained deaths. So the care home hypothesis doesn’t bear examination by the facts.

Speaking about the ONS data last week at the Science Media Centre, Professor David Spiegelhalter, Chair of the Winton Centre for Risk and Evidence Communication at the University of Cambridge, calculated that, over the seven weeks to 15 May, 8,800 fewer non-COVID-19 deaths than normal had occurred in hospitals. Since only a few care home residents normally die in hospitals, he argued that these deaths had not been ‘exported’ to care homes. By his own calculations, only 1,800 of the roughly 12,000 extra deaths were attributed to COVID-19, leaving 10,500 unexplained excess deaths. ‘If up to 8,800 of these deaths would normally have occurred in hospitals, this would leave at least 1,700 unexplained non-COVID deaths at home. This is a vital issue’, Spiegelhalter concluded, ‘if we are to understand the consequences of the actions taken.’

Another explanation might come from a recent study published on 28 April titled ‘Excess mortality in people with cancer and multimorbidity during the COVID-10 emergency‘. This has found that, due to the emergency, there has been a 45-66 per cent reduction in admissions to chemotherapy, and a 70-89 per cent reduction in referrals for early cancer diagnosis. As a result, the study estimates that deaths of newly-diagnosed patients with cancer in England over the next year, previously estimated at 31,354, could increase by 20 per cent to an additional 6,270 patients, the underlying cause of whose deaths may be cancer, COVID-19 or co-morbidities. Moreover, if people currently living with cancer are included, this figure could rise to 17,991 excess deaths.

The question is, what constitutes this ‘emergency’? The reduction in cancer services necessitated by what the Government told us is an overwhelmed National Health Service? Or the huge reduction in care for newly-diagnosed and existing cancer patients by hospitals that, in the month this study was published, had only 41 per cent of acute care beds occupied, nearly four times the normal amount of free acute beds at that time of year? In other words, was the lockdown of the UK, which included the radical reprioritising of the National Health Service on 17 March, and which led to the discharge of up to 25,000 hospital patients without being tested for SARs-CoV-2 into care homes, also responsible for these nearly 18,000 anticipated deaths, which have not yet appeared on any record of increased overall mortality?

A further explanation comes from the Office for National Statistics, which in its report on ‘Deaths involving COVID-19 in the care sector, England and Wales’, published on 15 May, revealed that there were 83 per cent more deaths from dementia than usual in April this year, with charities reporting that a reduction in essential medical care and family visits are responsible, A survey of 128 care homes by the Alzheimer’s Society corroborated this, reporting that 79 per cent said a lack of social contact is causing a deterioration in the health and well-being of residents with dementia, and with three-quarters of care homes reporting that General Practitioners have been reluctant to visit residents. Not only did a quarter of those whose deaths were attributed to COVID-19 have dementia — making it the most common pre-existing disease in such deaths — but in April there were a further 9,429 deaths from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease alone in England and 462 in Wales, 83 per cent higher than usual in England, and 54 per cent higher in Wales.

Finally, another explanation is that, after months of fearmongering backed by daily reports of mounting deaths out of all context or definition designed to terrify the British public into acquiescence to the lockdown, those at most risk from COVID-19 have been too terrified to go to hospital when they should have for fear of catching the virus, with visits to Accident and Emergency wards in April down by 50 per cent.

A measure of this is the increase in anxiety under the lockdown. In the most recent survey by the Office of National Statistics of the social impact of the coronavirus crisis, conducted between 14 and 17 May 2020, 72 per cent of adults in Great Britain were ‘concerned’ about the effect the coronavirus crisis was having on their life. This included concerns about our lack of freedom and independence, about our inability to make plans, about our ability or otherwise to work, and about our health, well-being and access to medical care. This rose to 73 per cent of those over the age of 70, and 82 per cent of those with underlying health conditions. Extraordinarily, 41 per cent of adults said they felt ‘unsafe’ or ‘very unsafe’ when leaving their home because of COVID-19; while for those with an underlying health condition this rose to 54 per cent. As a result, 1 in 7 people surveyed said they had not left home for any reason in the previous week, rising to 1 in 3 of those aged over 70 or with underlying health conditions. 91 per cent of adults said they are avoiding contact with older or vulnerable adults, with 11 per cent saying the people they are avoiding are those to whom they provide care. 43 per cent of people felt their well-being was being affected, rising to 55 per cent of those with underlying health conditions. Over 32 per cent of adults said they were experiencing high levels of anxiety, and 23 per cent reported they felt alone. Once again, these effects are increasing among those over 70 years of age or with underlying health conditions.

This fear, too, and the consequences it is having on mortality rates, is a product of the lockdown, for which the UK Government and the British media — the latter of which have behaved like vultures around the COVID-19 carcass — must bear full responsibility (which they will undoubtedly shirk).

* Since we published this article on 2 June, a study co-authored by titled ‘

More recently, on 15 July, the Office for National Statistics published its report titled Direct and Indirect Impacts of COVID-19 on Excess Deaths and Morbidity. This estimates the following number of excess deaths due to changes to health and social care implemented in response to the coronavirus:

- Changes to emergency care: 6,000 existing excess deaths in March and April 2020, with an additional 10,000 excess deaths if emergency care in hospitals continues to be reduced this year.

- Changes to adult social care: 10,000 non-COVID-19 excess deaths of care home residents in March and April 2020, with an additional 16,000 excess deaths over the whole year.

- Changes to elective care: could equate to 12,500 excess deaths over 5 years, with many non-urgent elective treatments having been postponed or cancelled by the NHS.

- Changes to primary and community care: could result in 1,400 excess deaths, with cancer diagnoses, GP referrals and emergency representations stopped or reduced.

- Medium-term impact of a lockdown-induced recession: 18,000 excess deaths occurring between 2-5 years following the lockdown due to increased heart disease and mental health problems.

- Long-term impact of a lockdown-induced recession: 15,000 excess deaths for younger people entering the labour market a few years before, during, and within a few years after the recession.

This adds up to a potential 88,900 excess deaths resulting from the UK Governments ongoing response to the coronavirus. In addition, the ONS estimates 17,000 excess deaths per year for as long as GDP remains at a low level indexed to multiple deprivation.

5. Collateral Damage

But an increase in mortality rate is not the only measure of the effects of this lockdown. Just as the excess deaths from cancelled operations, stopped treatment, the effects of increased anxiety and isolation on elderly people living alone or in care homes with serious illnesses, suicide in the face of withdrawn help and collapsed futures, and people too terrified to visit Accident and Emergency wards, will far outstrip the current number of deaths in the months and years to come, so the full impact of the lockdown of the UK will only be felt in the ‘new normal’ the Government has prepared for us.

The document titled ‘Our plan to rebuild: The UK Government’s COVID-19 recovery strategy’, published on 5 May, revealed that the Office for Budget Responsibility has estimated that the direct cost to the Government of the lockdown could rise above £100 billion in 2020-21. Under the Government’s Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme, 28 per cent of workers have been furloughed across all industries. Paying 80 per cent of the normal wages of 10 million workers up to £2,500 per month is currently costing the Government an estimated £14 billion per month. Running the scheme until the end of July will cost £63 billion, with the extension till the end of October announced by the Chancellor adding another £31 billion. Finally, the Self-employed Income Support Scheme has so far added a further £10.5 billion. In addition to these sums, support of approximately £330 billion in the form of guarantees and loans, equivalent to 15 per cent of GDP, has been made available to UK businesses. In April alone, the UK public sector borrowed £62.1 billion, almost as much as the £62.7 billion it borrowed in the whole of the last financial year. By the end of April, UK public sector debt was just under £1.9 trillion, equivalent to nearly 98 per cent of Gross Domestic Product.

In its latest bulletin on ‘Coronavirus and the latest indicators for the UK economy and society’, published on 28 May, the Office for National Statistics reported that 18 per cent of businesses had paused trading. 79 per cent of businesses in the UK had applied to the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme. 42 per cent of businesses had less than 6 months of cash reserves, rising to 58 per cent of those who has paused trading, while around 4 per cent of businesses who had not permanently ceased trading said they had no cash reserves.

The record fall in retail sales has continued, with volumes dropping by 18.1 per cent in April compared with 5.2 per cent the previous month. Clothing sales declined by 50.2 per cent, having already fallen by 34.9 per cent the previous month. Sales at food stores also declined by 4.1 per cent as lockdown measures were introduced. 72 per cent of exporting businesses in the UK said they are exporting less than normal, while 59 per cent of importers report that imports are lower than normal, with, respectively, 81 per cent and 80 per cent reporting a reduction in trade. In line with Government guidance, industries employing 11 per cent of the UK workforce have largely shut down. Between 6 and 19 April, 23 per cent of businesses had paused operations, and 47 per cent of workers were working remotely.

As a result of these measures, from January to March 2020 the total number of hours worked dropped by 12.4 million hours (1.2 per cent) compared with the previous year. This was the largest annual fall in a decade. This fall in hours worked occurred as lockdown measures were introduced, with average hours around 25 per cent below usual levels in the final week of March. There was also a 1.2 per cent annual decline in the number of paid employees, with 637,000 job vacancies between February and April, 170,000 fewer than in the three months to January 2020, and 210,000 fewer than a year earlier. The total job vacancies is the lowest since the first quarter of 2014, and the quarterly fall is a series record since 2001.

In its Monetary Policy Report for May 2020, the Bank of England forecast that the UK’s GDP would be close to 30 per cent lower in the second quarter of 2020 than it was at the end of 2019, that the economy would shrink by 25 per cent in the second quarter of the year, and could fall by 14 per cent in 2020. That’s more than twice the 6 per cent by which the UK economy shrunk in the 2008 recession. The Bank also forecast that unemployment is expected to more than double, from 4 per cent to a 26-year high of 9 per cent in 2021.

The latest claimant figures from the Office for National Statistics show almost 2.1 million people claimed unemployment benefit in April 2020, an increase of 856,500 from March 2020. Figures from the Department for Work and Pensions show 1.5 million claims for Universal Credit were made between 13 March and 9 April 2020, six times more than were made in the same period last year, and the most in a single month since its introduction in April 2013. This led to 1.2 million starts on Universal Credit. Despite the 300,000 denied claims, the overall number of people on Universal Credit increased in April by 40 per cent over the previous month to 4.2 million.

Perhaps the last word on the economic consequences of the Government imposed lockdown should go to the Financial Times, which reported that this year will experience the ‘fastest and deepest’ recession in the UK since the Great Frost of 1709, when Europe experienced the coldest winter for the past 500 years.

6. The Worst-Case Scenario

The response to all this, of course, is that if the UK Government hadn’t imposed, and the UK public hadn’t observed, the lockdown of the UK, the deaths from COVID-19 would be worse — many times worse, even — and perhaps reaching the figures published on 16 March by the now discredited Professor Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London, whose report on the Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand predicted 550,000 deaths in the UK if we did nothing, 250,000 if we isolated the vulnerable and quarantined the infected, and 20,000 if the Government that commissioned his estimates locked down the country.

This is an argument based on speculative predictions of the worst-case scenario based on computer simulations in which every minor change in input produces huge numerical changes in outcome. As an example of which, Ferguson’s estimation that 30 per cent of all those hospitalised with COVID-19 would require critical care was reportedly based on nothing more than a personal communication from a clinician who had been in China at the outbreak of the virus. On such back-of-the-envelope estimates were the Government’s fears of an overwhelmed NHS based. Indeed, even Ferguson’s report concluded that ‘No public health intervention with such disruptive effects on society has been previously attempted for such a long duration of time. How populations and societies will respond remains unclear.’

But although there is no way of knowing whether the number of deaths caused by COVID-19 and not merely with it mentioned on the death certificate would have increased if the UK wasn’t under lockdown, or whether, to the contrary, the overall mortality rate, including the unexplained excess deaths, would be less than it has been, let alone will be in the future, there are, nonetheless, two ways to estimate what may have happened. First, we can ask what effect the lockdown has had on the number of deaths in the UK from respiratory diseases other than COVID-19 that might be expected to have dropped due to the prohibition on leaving our homes without a ‘reasonable excuse’ and the social distancing measures imposed on us when we do; and, second, we can ask what has happened in other countries that have not imposed a lockdown of the severity of that in the UK.

The answer to the first of these questions is the easiest. The lockdown of the UK was imposed by the Government on 23 March. According to the Office for National Statistics, since the week ending 3 April, when we might expect the first deaths caused by a virus contracted since the lockdown to be registered, and 22 May, the last week for which we have data, there have been 11,403 deaths in England and Wales where the underlying cause was respiratory disease (ICD-10 J00-J99). Over the same 8-week period last year there were 11,006 deaths with the same underlying cause; in 2018 there were 11,650 deaths; in 2017 there were 10,455 deaths; in 2016 there were 12,057; and in 2015 there were 11,646. Over the previous five years, between 2015 and 2019, the average number of deaths between weeks 14 and 21 of the year in which the underlying cause was respiratory disease was 11,362. The obvious question in response to these figures is, if the lockdown of the UK has been successful at saving lives threatened by an infectious and contagious virus, why are there 41 more deaths this year in which the underlying cause was respiratory disease?

Now, one answer to that is that on some death certificates both respiratory disease and COVID-19 is written; and that the large number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 will therefore mean an increase in death certificates mentioning respiratory disease. However, this would be the wrong answer. The ONS makes it clear that, while COVID-19 (ICD-10 U07.1 and U07.2) merely has to be mentioned on the death certificate in order to appear in its breakdown of overall deaths, respiratory disease must be included as the ‘underlying cause’ to appear on the same. While the agency of COVID-19 deaths in the increase in overall mortality has clearly been hugely exaggerated by this method of calculation, which is a direct result of changes to disease taxonomy by the Department of Health and Social Care and official guidelines from the World Health Organisation on filling out death certificates, the number of deaths in which respiratory disease is the underlying cause has not. COVID-19 can appear on the death certificate of someone in whose death respiratory disease was the underlying cause, but COVID-19 can’t increase the number of deaths in which the underlying cause was respiratory disease.

The only logical conclusion that can be drawn from this is that the lockdown has had no effect on lessening the mortality rate from influenza, pneumonia, bronchitis, emphysema, asthma and other chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases included under this taxonomy. It is equally logical to deduce from this that the lockdown has had no effect on the rate of infection or contagion of non-COVID-19 respiratory diseases spread by social contact, such as seasonal influenza and pneumonia. It is, therefore, logical to conclude that, despite the Prime Minister claiming that the lockdown has saved ‘half a million people’ in the UK from COVID-19, there is absolutely no evidence to support this claim. There is, however, plenty of evidence to support the counter accusation that the lockdown has already directly or indirectly killed many thousands of British citizens and is likely to kill thousands more in the future.

7. Comparative Government Responses

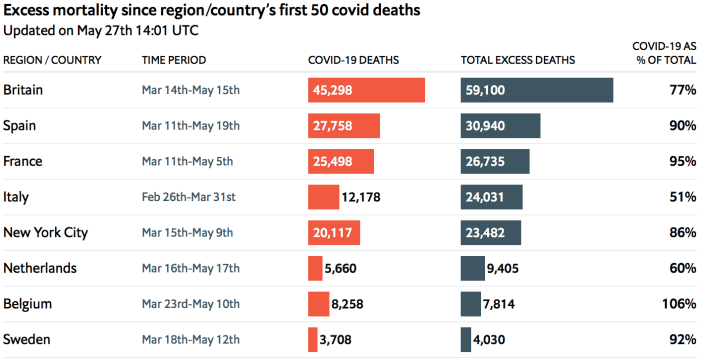

Answering the second question is a little more complex. The gap between total excess deaths and deaths attributed to COVID-19 is not confined to the UK, but has appeared in other countries under similarly severe lockdowns. According to a regularly updated article in the Economist titled ‘Tracking covid-19 excess deaths across countries’, as of 27 May, Britain had 13,802 unexplained deaths in excess of those officially attributed to COVID-19 (23 per cent of the total), Italy had 11,853 (an extraordinary 49 per cent of excess deaths), Netherlands 3,745 (40 per cent), Spain 3,142 (10 per cent), and France 1,237 (5 per cent); while outside of Europe, New York City alone had 3,365 (14 per cent).

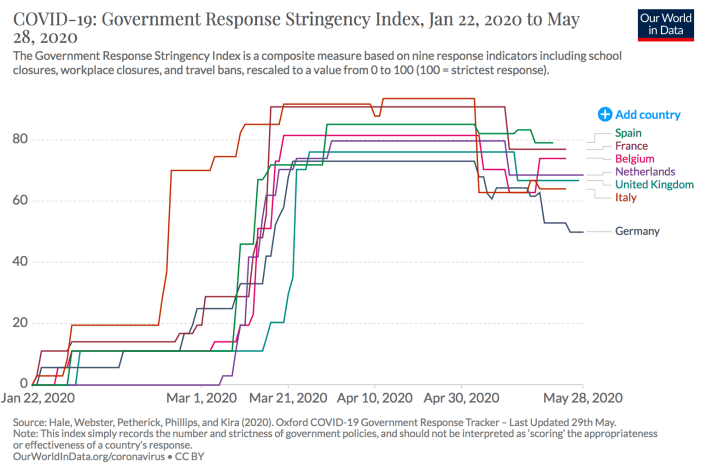

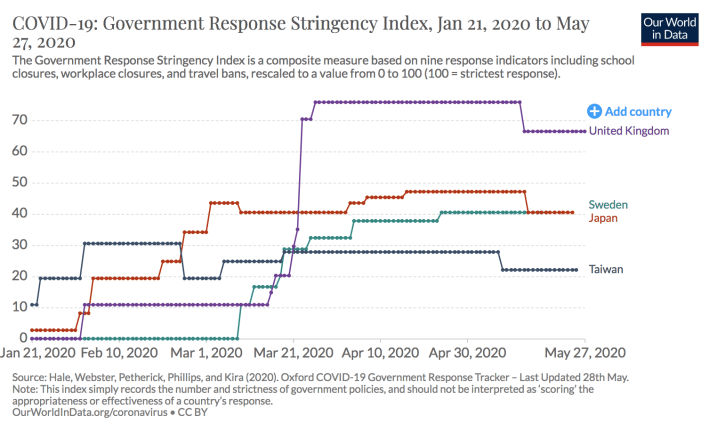

Helpfully for us, the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) systematically collects information on several different common policy responses that governments have taken, records the stringency of each policy on a scale to reflect the extent of government action, and aggregates these scores into 17 policy indices. These are divided into the following three categories: containment and closure policies, economic policies, and health system policies. This data has been used to produce interactive global maps tracking ‘Policy Responses to the Coronavirus Pandemic’, which are available on the website Our World in Data. These chart nine metrics of where and when the following policies of ‘lockdown’ were implemented: 1) school closures, 2) workplaces closures, 3) cancellation of public events, 4) restrictions on public gatherings, 5) public information campaigns, 6) stay-at-home restrictions, 7) public transport closures, 8) restrictions on internal movement, and 9) international travel controls. Together, these policies produce a Government Response Stringency Index ranging from 0 to 100, with 100 being the strictest.

On 16 March, when the Government imposed Social Distancing measures, the UK registered 20.37 on this Stringency Index. On 21 March the index rose to 29.63, and the following day it rose again to 35.19. Then on 23 March the lockdown was implemented, and the index doubled to 70.37. Three days later, on 26 March, the Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (England) Regulations 2020 (the Regulations) were made law, and the index rose to 75.93, where it stayed until 12 May, after which the Government’s ‘sketch of a roadmap for reopening society’ came into effect. From 13 May, when workers were encouraged by the Government to return to work and UK citizens were permitted to leave home, the index dropped to 66.67, where it has remained since. It was over these 7 weeks of lockdown, when the stringency index of the UK Government’s response to the coronavirus crisis was at its highest, that the UK economy was forced into the worse depression in over 300 years, 12,394 unexplained excess deaths and perhaps 35,688 excess deaths without established causality from COVID-19 occurred.

How equivalent lockdown measures affected the economies of other countries is beyond the scope of this article; but we can compare countries with a similar index rating and look at their official death toll from COVID-19. As I concluded in my previous article on Manufacturing Consensus, in the UK, at least, the calculation of these deaths has become almost meaningless, so loose is the criteria for counting them; so comparing the wildly inaccurate figures in the UK with the possibly as inaccurate figures in other countries is never going to arrive at any accurate calculation. However, so conclusive is the evidence from countries with a far lower stringency index than the UK that the huge degree of inaccuracy in how the UK Government calculates and reports so-called ‘COVID-19 deaths’ doesn’t matter.

Let’s start with European countries with a similar Government Response Stringency Index to the UK and similar levels of infrastructure and health services. Between 17 March and 10 May France had an index rating of 90.74, even higher than the UK, since when it has dropped to 76.85. Italy, which on 4 March rose to 74.54, comparable to UK under lockdown, by 12 April had risen to 93.52, where it remained until 4 May. Spain, which on 17 March had an index of 71.76, by 30 March had hit 85.19, where it remained until 4 May, when it dropped to 81.94, and currently sits on 79.17. Finally, on 22 March Germany had an index rating of 73.15, remaining there until 4 May, when it dropped to 68.06. It has since dropped to an even 50.00. All these European countries, therefore, have been under as severe or more stringent lockdown measures for as long as or longer than the UK. The exception is Germany, which has a slightly less high stringency index than the UK, but for almost the exact same period of time.

Most people in the UK will be familiar by now with how these measures have fared in their respective countries. I won’t mention here the number of so-called ‘cases’, which refer not to people with COVID-19 but to those infected with SARs-CoV-2, and which is a measure almost entirely dictated by the number of tests conducted, which varies hugely from country to country. However, according to the official figures, as of today, 2 June, the countries with the highest number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 are, in order, the UK with 39,045; Italy with 33,475; France with 28,833; and Spain with 27,127. These are, of course, the European countries with the largest populations, so we might expect them to have the highest number of deaths; but they also have the highest number of deaths per capita, with Spain on 580 deaths per million of the population, the UK on 575, Italy 554 and France 442. Only Belgium, a far smaller country with 9,505 official COVID-19 deaths, exceeds these proportions with 820 deaths per million; and between March 20 and 4 May Belgium had an index rating of 81.48, and currently sits on 74.07, so lockdown doesn’t appear to have done it any good either. While the Netherlands, with 5,967 deaths attributed to COVID-19 at 348 per million of the population, on 23 March had an index rating of 74.07, rising to 79.63 between 31 March and 3 May, and currently sits on 68.52. So lockdown also doesn’t appear to have done it any good; but it has done a lot of harm, with 3,745 unexplained excess deaths as of 27 May.

The exception, again, is Germany, which with the highest population in Europe has an official toll of 8,618 ‘COVID-19 deaths’ at 103 deaths per million people. But far from proving the effectiveness of lockdown, Germany’s record suggests that SARs-CoV-2 is nothing like as virulent as the governments of the UK, Italy, France and Spain are claiming, and that the increased overall mortality rate in the countries supposedly worst-hit by COVID-19 have other causes, which Germany — with nearly 3 times as many hospital beds per 100,000 people compared to the UK and 4 times as many intensive care beds per 100,000 people as the NHS — has managed to negate. In the complete and unexplained absence of accurate figures establishing the actual cause of deaths officially attributed to COVID-19 in these countries, it’s impossible to be certain; but taken together, what these figures strongly suggest is not only that lockdown across these countries, the worst affected in Europe, did nothing to slow the rate of infection from SARs-CoV-2, but that these measures most likely increased the case fatality rate from COVID-19. It undoutedly increased the overall mortality rate in these countries.

8. Alternatives to Lockdown

But what of the countries that have not imposed lockdowns, or not to the same degree of severity as the UK? What do they have to tell us about the negative and unnecessary effects of the Government’s decision?

Further evidence in support of the ineffectiveness of lockdown comes, of course, from Sweden. Despite immense pressure from the international community (which is to say, the USA) and the World Health Organisation, Sweden’s Government Response Stringency Index has never risen above 40.74, which it only reached on 24 April. This was in response to a sudden increase in mortality on the 21 and 22 of April, when the deaths of 357 people were attributed to COVID-19. For the three weeks prior to that, starting from 4 April, it was 37.96; and before that 32.41. With a population of just over 10 million, Sweden has an official total of 4,468 ‘COVID-19 deaths’ as of 2 June, at 433 deaths per million of the population. Despite being below Spain, the UK, Italy and France, so hysterical have been the arguments for the benefits of lockdown that the Swedish Government was accused of ‘playing Russian roulette’ with the lives of its citizens for leaving bars, restaurants and schools open but limiting public gatherings to 50 people, advising citizens to avoid non-essential travel on public transport, and encouraging the sick and elderly to stay at home, but not shutting down the economy. In response to this accusation, Anders Tegnell, the State Epidemiologist of the Public Health Agency of Sweden to whose advice the Government has listened, responded that, to the contrary, it was the UK and other nations imposing lockdowns that were indulging in an experiment that had no precedent in national responses to previous viral epidemics. Where Sweden has admitted failing is in not protecting the elderly and sick in care homes where, up to 14 May, 48.9 per cent of all deaths attributed to COVID-19 were resident. In this it shares something with England and Wales, where 11,650 of the 41,220 deaths attributed to COVID-19 by 15 May, 28.2 per cent of the total, occurred in care homes.

What this comparison suggests is that the less restrictive guidelines issued by the Swedish Government and the severe lockdown imposed by the UK Government both failed to protect those most at risk from COVID-19. However, the far higher mortality rate in the UK outside of care homes compared to Sweden also suggests, once again, that the lockdown caused more deaths than it saved. In an article titled ‘The Invisible Pandemic’, published on 5 May in the medical journal The Lancet, Johan Giesecke, the Swedish physician and Professor Emeritus at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm, and the former Swedish State Epidemiologist, wrote:

‘It has become clear that a hard lockdown does not protect old and frail people living in care homes — a population the lockdown was designed to protect. Neither does it decrease mortality from COVID-19, which is evident when comparing the UK’s experience with that of other European countries.

‘PCR testing and some straightforward assumptions indicate that, as of April 29, 2020, more than half a million people in Stockholm county, Sweden, which is about 20–25% of the population, have been infected. 98–99% of these people are probably unaware or uncertain of having had the infection; they either had symptoms that were severe, but not severe enough for them to go to a hospital and get tested, or no symptoms at all.

‘These facts have led me to the following conclusions. Everyone will be exposed to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, and most people will become infected. There is very little we can do to prevent this spread: a lockdown might delay severe cases for a while, but once restrictions are eased, cases will reappear. I expect that, when we count the number of deaths from COVID-19 in each country in 1 year from now, the figures will be similar, regardless of measures taken.’

The most important difference between Sweden and the UK, however, is neither the increase in overall mortality nor the number of deaths officially attributed to COVID-19, but the respective state of their economies. All the evidence points to the conclusion that, higher as the percentage of deaths already is in the UK (575 per million of the population) compared to Sweden (443 per million), the UK will continue to ruin and lose lives to the negative economic effects of the lockdown for years to come, while Sweden’s economy has suffered far less in comparison. Undoubtedly, as a high export economy, Sweden will feel the effects of the rest of Europe’s panic; but the country’s statistics office has just reported adjusted GDP growth of 0.4 per cent for the first quarter of 2020. And while the National Institute for Economic Research has predicted a 7 per cent reduction in Sweden’s economy this year, this is half the 14 per cent the Bank of England has predicted for the UK. What is certain is that the UK, for all the opprobrium our arrogant and fearmongering media has flung at Sweden, has nothing to say to anyone about how they should or shouldn’t respond to the coronavirus.

Even more damaging to the claims for the efficacy of lockdown are the examples of Japan and Taiwan. The former, with a population of 126.5 million, 45 per cent of which live in three densely populated cities, has attributed just 892 deaths to COVID-19 at a rate of 7 deaths per million of the population; while the latter, with a population of 23.8 million, has attributed just 7 deaths to COVID-19 at a rate of 0.3 per million. Yet both these countries, situated off the coast of China and therefore among the first countries to report cases of infection (respectively, 16 and 21 January), have employed some of the lightest measures in the world, barely warranting the term ‘lockdown’. Rising by steady increments to 43.52 on 2 March, Japan’s Government Response Stringency Index took until 16 April to rise to 47.22, at a time when the UK’s was at 75.93. Social distancing was encouraged but not imposed by emergency regulations, and music venues and gyms were closed; but bars and restaurants stayed open, although not as late, and people still went to work. On 25 May, after 10 days at an index rating lowered still further to 40.74, Japan’s Prime Minister announced the end of its State of Emergency, without a lockdown ever having been imposed.

The Taiwanese Government has been even less severe. After an initial rise to 30.56 on 2 February, its index rating had dropped to 19.44 by 25 February, rose again on 19 March to 27.78, where it stayed until 8 May, when it dropped down to where it remains now at 22.22. Throughout these months its citizens kept working and its economy kept working. This isn’t to say that Taiwan hasn’t introduced programmes to track and trace its citizens via their mobile phones, used monitors to test their temperatures when entering public buildings, offices and schools, and issued severe fines for non-compliance; but none of these intrusive measures, which our Government is in the course of introducing in the UK, will have done anything to stop the spread of the virus or reduce the infection fatality rate from SARs-CoV-2. Quarantining was imposed, and with just 443 official ‘cases’ this appears to have been the key decision in slowing the rate of infection; but this was done early, and without a lockdown being imposed. In the UK, by comparison, we are imposing the same measures but in reverse, first forcing the economy into an unnecessary depression that will be felt for a generation, then ostensibly attempting to trace and contain a highly infectious virus that has been in the country for at least 5 months.

It’s important to remember, too, that the Government Response Stringency Index is an indication of policies, not of their implementation or effectiveness. In India, where 1.3 billion people have officially been under a lockdown with an index rating of 100 — the highest possible — since 22 March, marginally dropping to 96.3 on 20 April and currently on 79.17, 78 million people live in slums and tenements, 18 million children live on the streets, 13.7 million households live in informal settlements, and 1.7 million people don’t have a home of any sort to be confined to. Despite these conditions, which severely restrict the imposition of a lockdown, there have been only 5,612 deaths officially attributed to COVID-19 at a rate of 4 deaths per million of the population, since the first official death on March 12. And out of the 101,487 ‘cases’ of infection that have had an outcome so far, 95,875 — 94 per cent — have recovered.

Is this really the outcome of a deadly virus sweeping for 3 months through a country in which 640 million people live in poverty and 69 per cent of all Indian houses have only one or two rooms, making quarantining measures impossible? Africa, a similarly impoverished continent, which Bill Gates recently described falling into disaster with a ‘2 per cent overall death rate’, has rather inconveniently reported just 4,344 deaths attributed to COVID-19 out of a population of 1.34 billion (or 0.0003 per cent). Is this evidence of a civilisation-threatening virus? Or is it, to the contrary, further proof of what the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US are belatedly establishing is an overall infection fatality rate between 0.2 percent and 0.3 percent, compared to the 0.9 per cent assumed by Professor Neil Ferguson in the report justifying the lockdown of the UK?

Proclaimed a ‘mystery’ by the British press otherwise insistent on imposing ‘the best scientific opinion’ on the British people whatever the cost, it is impossible for the coronavirus to be anything like as virulent as we have been led by the nose to believe and leave Japan, Taiwan, India and Africa almost untouched relative to their overall mortality rate. It’s a principle of science that the natural world behaves in repetitive ways which, studied for long enough, reveal its mysteries, but only to the observer who doesn’t come to the microscope, so to speak, with their head full of preconceptions, and above all when they’re not blinded by propaganda serving the political ends of the Government. We’ve been lied to — a lie that may one day kill as many people as the lie that has led to the death of hundreds of thousands of Iraqis as the result of an equally fictitious reason to go to war against an enemy that did not threaten the UK, but whose defeat would make the perpetrators of the war richer and more powerful. I want to end, therefore, by looking at who is getting rich and who is gaining power at whose expense from the coronavirus lie.

9. Spreading Inequality

None of what I’ve written above is to say that the coronavirus crisis, which is a product of government reactions to SARs-CoV-2, won’t negatively impact the poorest and most vulnerable members of society. The ‘collateral damage’ from the so-called war on COVID-19, in both lives lost and economic impact, has not been suffered evenly. Despite the Government’s worn-out mantra — dutifully repeated by an obedient public — that ‘we’re all in this together’, the negative effects of the lockdown have been, and will continue to be, borne by the poorest members of the UK. Coronavirus is named after the crown-like spikes that bind to the host cell, and parasitical aristocrats, landowners and landlords continue to receive rents on their land and properties from households, businesses and workers prohibited by the Government from making a living on them. But the exacerbation of economic inequality goes farther than a rentier society. While many capitalists will lose fortunes to this unprecedented and extended cessation of global trade, we can expect them to recuperate those losses, just as they did after the financial crisis of 2008, from the poorest and most vulnerable members of UK society through policies of fiscal austerity that will make the last 12 years look like an orgy of public expenditure. Indeed, since I published this article on 2 June, it has been reported that UK-registered billionaires have seen their wealth grow by 20 per cent during the lockdown, with the 45 richest individuals increasing their wealth from £121.57 billion to £146.61 billion in just three months, all while claiming hundreds of millions of pounds of public money for the bailout of their businesses and the furlough of thousands of workers facing the sack when that funding is withdrawn.

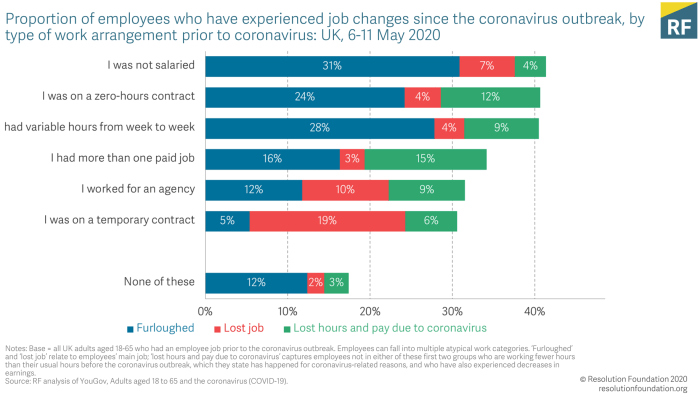

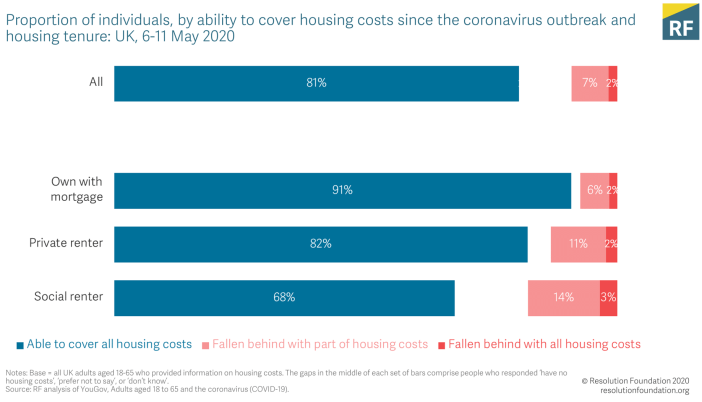

The Resolution Foundation, an independent think-tank focused on improving living standards for workers on low to middle incomes, has produced reports on both The effects of the coronavirus crisis on workers, published on 16 May, and Coping with housing costs during the coronavirus crisis, published on 30 May. This is not my research, so I will only report its findings; but these show that — bad as the forecasts for ‘the nation’ are, and eagerly as the Government’s package of fiscal support has been greeted by liberals as the return of ‘socialism’ — the economic costs of the lockdown are already being distributed unequally across the classes.

From online interviews with over 6,000 employees aged 18-65, plus fieldwork undertaken between 6-11 May, the first report found that 30 per cent of the lowest-earning fifth of employees have either been furloughed or lost their jobs, and 22 per cent of the next lowest-earning fifth, compared to 9 per cent of the top-earning fifth of employees. This discrepancy gets greater for different types of work. 38 per cent of unsalaried workers, 32 per cent of workers with variable hours, 28 per cent of workers on zero-hour contracts, and 22 per cent of agency workers, have been furloughed or lost their jobs under the lockdown, with a huge 19 per cent of workers on a temporary contract losing their jobs outright. And while, respectively, just 23, 17 and 25 per cent of furloughed workers in the bottom three fifths of earners are receiving 100 per cent of their pay, in the second highest-earning fifth that figure jumps to 31 per cent.

Things are even worse for the self-employed, with only 39 per cent having applied or planning to apply to the Self-employed Income Support Scheme. By comparison, 83 per cent in the highest-earning fifth of employees were currently working some or all of the time from home last month, and 60 per cent expect to work from home more after the lockdown than they did before. Unsurprisingly, expectations of the future are low, with 13 per cent of all those currently working thinking it fairly or very likely or almost certain that they will lose their job over the next 3 months, 15 per cent have similar expectations of being furloughed, and 23 per cent expect their hours to be reduced.

As for the effects of the lockdown on housing, the inequality being spread by the Government’s measures is even greater, as one would expect of a country in which so much of the national wealth is invested in property, and the single largest monthly or weekly expenditure for most households is on their housing costs. 24 per cent of social renters and 20 per cent of private renters have either been furloughed or lost their job, compared to 14 per cent of mortgagors. But the effects of tenure type become more apparent when looking at the ability to cover housing costs. Only 8 per cent of home owners with a mortgage have failed to cover their housing costs under lockdown, compared to 13 per cent of private renters; while 17 per cent of social renters have fallen into rent arrears, twice the rate of mortgaged home owners.

There are various reasons for this huge difference in the ability of households to meet housing costs. One reason is because home-owners entered the lockdown with lower housing costs relative to their incomes (an average of 13 per cent) compared to social renters (18 per cent) and private renters (a massive 32 per cent). Another reason is because home-owners are in general wealthier, with only 13 per cent holding no savings before the lockdown, compared with 23 per cent of private renters and 47 per cent of social renters. But there is a third reason, which is that homeowners have received greater support from the Government.

13 per cent of mortgaged home owners have applied for a mortgage holiday in recent weeks, with 92 per cent being granted relief from their repayments for three months. In stark contrast, while 10 per cent of private renters have tried to lower their housing costs under the lockdown, either through negotiating a lower rent with their landlord or being granted a rent holiday, only 50 per cent have been successful. The even lower 4 per cent of social renters who have attempted to renegotiate their rent with local authorities or housing associations have had the same rate of success. Admittedly, the Government instructing a handful of lenders to grant a holiday to mortgagors is easier to impose through policy than compelling thousands of landlords to do the same for private renters, and under current legislation private renters and, increasingly, social renters have little or no rights. But this is a failure not only of existing housing legislation but also of the Government’s indifference to the financial plight of renters under lockdown.

As a result of this protection of UK residential property values over and above ensuring the ability of UK citizens to afford to live in those properties, 37 per cent of renters who have made a claim for Universal Credit since the lockdown began are currently unable to meet their housing costs. Again, as a result of this failure of the benefit system to compensate households financially for being refused the right to support themselves financially, 24 per cent of private renters and 19 per cent of social renters are cutting down on other items in order to afford their rent, with 12 per cent of all renters experiencing material deprivation as a result. In comparison, 16 per cent of mortgaged home-owners have cut expenditure to afford housing costs, with only 4 per cent experiencing deprivation.

The consequences of all this are becoming apparent. 20.56 million people in England alone, 36 per cent of all households, rent from a private or social landlord, and they’ve been thrown to the wolves by the Government. Despite the extension of the notice period for evictions of private and social renters from 2 to 3 months under the Coronavirus Act 2020 (something the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government dishonestly tried to pass off as a 3-month ‘ban’), and which ends on 25 June, tens — and perhaps hundreds — of thousands of renters are currently living with the threat of eviction: either under Section 21 of the Housing Act 1988, which empowers landlords to evict tenants without reason on two months’ notice, or under a Section 8 notice, which allows a landlord to evict through possession proceedings on the grounds of non-payment if a tenant hasn’t paid rent for 8 weeks.

So far, just as the ludicrously underfunded ‘Everyone In’ programme to get rough sleepers off the street at the height of the coronavirus crisis appears to have been abandoned by the Government like the public relations stunt it was, so too the Government has resisted all calls either to ban evictions of renters or to raise housing benefits sufficient to afford rents.

10. Outsourcing the State

That the poor are getting shafted by a Government that has first removed their ability to work then told them that a 20 per cent wage cut or life on Universal Credit is sustainable for millions of workers that were ‘just about managing’ on their previous salaries shouldn’t surprise anyone who has observed the steady dismantling of the welfare state over the past decade. But the greed and opportunism with which the rich are profiting from the coronavirus crisis may surprise those who have chosen to believe the Government’s lies about us coming together during this ‘period of national emergency’. But surprising or not, things are very different at the other end of the economic scale.

Under new procurement policy published on 18 March and justified by the ‘extreme urgency’ of responding to the coronavirus, at least 115 Government contracts worth over £1 billion have been directly awarded without tender to private companies. The largest of these include Edenred, the French catering company awarded a contract worth £234 million by the Department for Education to feed children eligible for school meals; the US–owned Brake Brothers and the South African-run BFS Group, which have been directly awarded contracts worth a combined £208m by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to deliver food boxes to vulnerable people; and Randox Laboratories, a UK-owned healthcare firm directly awarded a contract worth £133 million by the Department of Health and Social Care to produce testing kits for SARs-CoV-2. Other contacts include £60 million directly awarded by the Department for Education to Computacenter to supply computers; a combined £57 million awarded by Health and Social Care Jobs in Northern Ireland to Bloc Blinds to supply face shields; £23 million directly awarded by the Department of Health and Social Care to Oxford Nanopore; and £20 million directly awarded by HSCNI to Techniclean, again for the supply of face masks.

And as the private sector is being awarded contracts paid for with public money, so a public sector starved of funding is having its services outsourced to private companies. That this should be perpetrated against the NHS while it is being elevated to heroic status by Government propaganda should not surprise anyone who has watched the creeping privatisation of health services in the UK over the past 40 years.

On 2 December, 10 days before the country voted the Conservative Government into office in the 2019 General Election, Siva Anandaciva, Chief Analyst at the King’s Fund think-tank, a member of the Office of Health Economics Policy Committee and chair of the National Payment Strategy Advisory Group for NHS England and NHS Improvement, wrote that the NHS ‘heads into winter with A&E performance at its worst level since current records began, 4.6 million people on hospital waiting lists and with 100,000 vacant staff’. This, he explained, was not only because of years of sustained disinvestment in the NHS, but more immediately because the extra Government funding typically released late in the year in anticipation of winter influenzas and respiratory diseases had been withheld as a result of the Election and subsequent cancellation of the Autumn Budget. Add to that the Government changes to NHS pensions and the effects of Brexit, and Anandaciva told the Guardian:

‘In recent years the NHS has defied the odds and somehow managed to cope despite warnings about the impact of winter pressures. This time it is heading into what is likely to be the worst winter since modern records began in the eye of a perfect storm.’

We’ve already looked at some of the cumulative effects of underfunding in the NHS on excess deaths both unexplained and attributed to COVID-19; but the entrepreneurs in Government know a business opportunity when they see one. Having denied any connection between the failures to adequately fund public health services and the perfect storm predicted last winter, the Government has taken advantage of what it has insisted is an NHS ‘overwhelmed’ by COVID-19 deaths, and which could only be ‘saved’ by the lockdown, to outsource health services to private contractors.

Despite the new policy requiring any contracts awarded under emergency regulations to be published by the contracting authority ‘within 30 days of awarding the contract’, the financial values of some of the key contracts in the Government’s response to the coronavirus crisis have yet to be disclosed. Specifically, contracts to operate drive-through coronavirus testing centres have been awarded to the accountancy and management consultancy firm Deloitte, which is managing payrolls, rotas and other logistics at national level, and has appointed the outsourcing firms G4S, Mitie, Serco, Sodexo, plus the pharmacy retailer Boots, to run the centres. Together with tech companies Palantir and Faculty, all these private companies have been running test centres and creating a COVID-19 data store since March, yet the relevant Government departments have refused to disclose the value of the contracts. While in April, Serco was directly awarded a contract by the Department for Work and Pensions potentially worth £90 million to provide emergency contact centre services for vulnerable people who are self-isolating. Deloitte is also co-ordinating the UK Lighthouse Labs Network, a coalition of public bodies and private companies formed to conduct testing for SARS-CoV-2, and which have been subcontracted to GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Amazon and Boots. Dozens of private companies have been awarded contracts to build, run and support the largely empty Nightingale Hospitals, including consultancy firm KPMG, Mott MacDonald, Archus and Interserve, with private security being supplied by G4S. Deloitte is also overseeing the production of protective equipment and other stock, with Clipper Logistics one of the supply chains awarded contracts to deliver protective equipment to NHS trusts, care homes and other healthcare workers.

Perhaps the clearest indicator of this further step forward in privatising health services under the cloak of the lockdown is that the Department of Health and Social Care has instructed NHS trusts that, from 4 May, 16 items of equipment, including PPE, ventilators, computerised tomography scanners, mobile X-ray machines and ultrasounds, must no longer be purchased directly by local NHS managers. Instead, under its new Government contract, Deloitte will centrally oversee all procurement, effectively outsourcing the health and safety of the UK population to private contractors.

Many of these companies, both those whose contracts have been published and those that haven’t, have a history of incompetence, malpractice, fraud, price-fixing, prosecution, financial mismanagement, misconduct, bribery, illegality, breaches of security, confidentiality and contract, abuse of human rights, dubious ethical practices and conflicts of interest that, were the tendering process properly scrutinised by the Institute for Government, should preclude them from even bidding for Government contracts, let alone being awarded them without competition, oversight or disclosure. I’ve written about these before, but they bear repeating and remembering.

- Edenred, the French-owned catering company with just 145 employees and revenues of £11.8 million given the responsibility of distributing food vouchers to 1.3 million children eligible for school meals, has been accused of woeful preparation that has left thousands of UK children going hungry.

- BFS Group; the UK-based foodservice wholesaler and distributor and wholly-owned subsidiary of the South-African holding company Bidcorp, suffered losses of £14.8m in the year to June 2018 largely due to its logistics division, which reported operating losses of £37.7 million.

- Randox, a UK company in the in vitro diagnostics industry, in February 2017 faced charges against two employees arrested on suspicion of perverting the course of justice amid allegations of data tampering within its testing services used by police in England and Wales, and currently pays Owen Paterson, the Conservative MP for North Shropshire and former Secretary of State for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, and who has a history of lobbying Government Ministers on behalf of companies he advises, a £100,000 per year consultancy salary.

- Deloitte, despite being the largest professional services network in the world, in 2016 failed to protect itself against a cyberattack that breached the confidentiality of its clients and 244,000 staff, allowing the attackers to access usernames, passwords, IP addresses and health information.

- G4S, the UK’s largest security services company, has been accused of using detained immigrants as cheap labour in prisons, extreme misconduct in child custodial institutions in the UK and the US, and of collaborating in police telephone data manipulation.

- Mitie, the UK strategic outsourcing company that has businesses in immigration detention and deportation, prisons and custodial health services, in 2016 was found by the prison inspectorate to have facilities that were ‘dirty’, ‘rundown’ and ‘insanitary’.