Brixton Gardens, architectural rendering by Leonie Weber

What is ‘community-led housing’? The phrase is used these days with increasing frequency, but what does it mean? How can it embrace the resource and advice hub set up by the London Mayor to build more affordable housing, and which has just been allocated £38 million of funds, and, at the same time, proposals made by campaigners trying to save the Old Tidemill Wildlife Garden in Lewisham, which has been condemned to demolition and redevelopment by a council and housing association acting with the financial support and planning permission of the same London Mayor? Beyond its rhetoric of government decentralisation and resident empowerment, what does ‘community-led’ mean in practice? Is it an initiative by London communities in response to the threat to their homes of estate demolition schemes implemented by councils in which they no longer have any trust? Is it emblematic of the kind of initiative envisaged by the former Conservative Prime Minister, David Cameron, in his image of a Big Society that takes back responsibility for housing UK citizens from the state and places it in the hands of entrepreneurs, whether small developers or housing co-operatives? Is it a way to relieve London councils of the responsibility for housing their constituents? Is it just another term in the increasingly duplicitous lexicon of Greater London Authority housing policies designed to hand public land and funds over to private developers and investors under the guise of being ‘community-led’? Or is it a genuine, if limited, solution to London’s crisis of housing affordability, one that will finally build and manage at least some of the homes in which Londoners can afford to live? In this article we address these questions through looking at ‘Brixton Gardens’, a proposal for a co-operative housing development that was made last year by Architects for Social Housing in partnership with the Brixton Housing Co-operative.

1. Greater London Authority

The Architects for Social Housing/Brixton Housing Co-operative proposal was made in response to the London Mayor’s Small Sites x Small Builders programme, which was published by the Greater London Authority (GLA) in January 2018. According to the guidance for proposals and submission proforma, this programme aims to:

- Bring forward small, publicly-owned sites for residential-led development, in a streamlined way;

- Invigorate new and emerging ‘sources of supply’, including small developers, small housing associations and community-led housing organisations.

The GLA invited bids from small innovative developers, addressing what they call ‘challenging’ sites with creativity and a desire to deliver new homes. They state that they welcome a range of new entrants to the market, including community land trusts, housing co-operatives, co-housing groups, and custom- or self-builders, as well as registered providers of social housing who may be looking to develop new housing. There is no eligibility criteria for those making proposals, with the GLA stating they are interested in organisations who intend to deliver their proposed scheme and help build more homes for Londoners.

The GLA suggested that sites where affordable and/or community-led housing is required may benefit from partnership with other organisations; and that although public landowners are interested in the financial offer for the site, they are looking for a degree of confidence in the deliverability of the proposal and the intention to build good quality homes, promptly, with innovative solutions to what are complex sites.

As for the thorny question of what ‘community-led’ housing is, the GLA’s resource and advice hub says that it must share the following principles:

- Meaningful community engagement and consent occurs throughout the development process. Communities do not necessarily have to initiate the conversation, or build homes themselves, though many do;

- There is a presumption that the community group or organisation will take a long-term formal role in the ownership, stewardship, or management of the homes; and

- The benefits to the local area and/or specified community are clearly defined and legally protected in perpetuity.

2. Transport for London

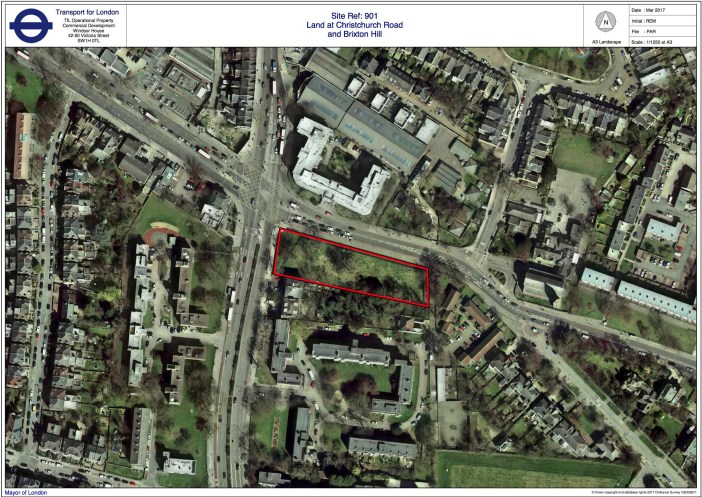

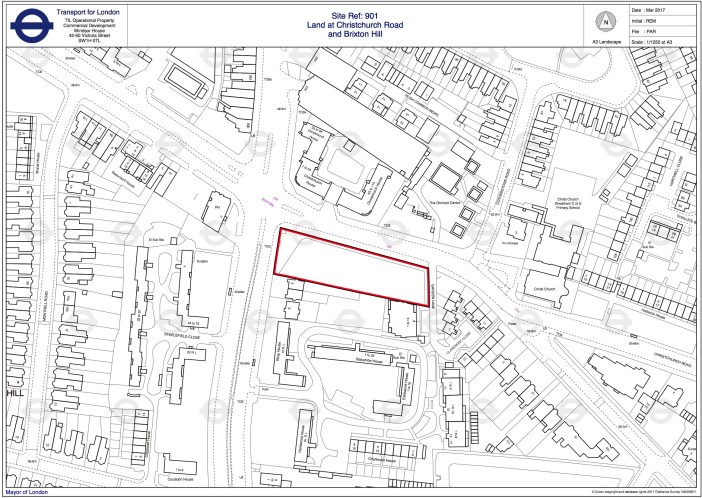

The site for which ASH and the Brixton Housing Co-op bid is on the corner of Streatham Hill and Christchurch Road, which here makes up a portion of the South Circular Road (A205), in the London borough of Lambeth, half a mile north of Streatham Station. This is held in freehold by Transport for London (TfL), which has released an information pack on the site through GVA property agency. The surrounding area is comprised predominantly of residential buildings, with some commercial buildings along Brixton Hill and towards Streatham Hill. Additionally, a number of schools are within close proximity, and Christ Church lies to the east of the site. The site measures approximately 0.80 acres (0.32 hectares) in size and comprises a vacant rectangular, grass-covered plot with a number of mature trees in the western portion. The site is currently fenced along the western, northern and eastern boundaries, but was previously in residential use, when it held a number of pre-fabricated bungalows that were demolished after 1976. Purpose-built flat blocks lie to both to the north and the south of the site.

Planning Requirements

The site was not allocated for a specific use. However, it was identified as housing- amenity land local open space within the Lambeth Open Space Strategy 2013. It is not situated within a Conservation Area, although the outer boundary of the Rush Common and Brixton Hill Conservation Area lies on the northern side of Christchurch Road, and the trees on the site are subject to Tree Preservation Orders. There are no active planning applications or permissions for a change of use or redevelopment of the property at the present. The London Borough of Lambeth was undertaking a partial review of its 2015 Local Plan and expected a consultation to take place in late 2017. Transport for London had made representations to the local authority to enable the site to be allocated for residential use as part of this review process, and it was anticipated that a future residential planning application will need to follow the outcome of this process.

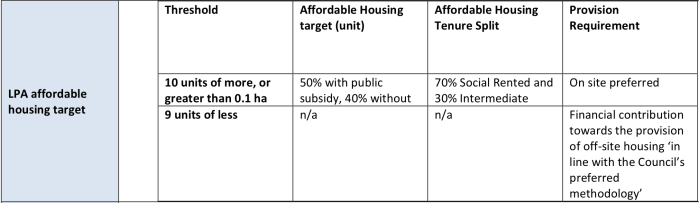

Standing opposite the Rush Common and Brixton Hill Conservation Area, the site is also opposite a number of listed buildings that are part of the heritage Grade II-listed Aspen House Open Air School and approximately 50 metres to the west of the Grade I-listed Christ Church. Due to the site’s location within a designated local view and in the setting of a number of listed buildings, the local planning authority does not consider tall buildings to be appropriate at this location. TfL has previously submitted two planning applications in 2004 and 2007 for residential development on the site, both of which were refused by the local planning authority and dismissed at appeal. In the TfL Town Planning Overview for the Christchurch Road site, dated 24 July 2017, the Affordable Housing target of the local planning authority, Lambeth council, was put at 50 per cent with public subsidy, 40 per cent without, of which 70 per cent must be for social rented and 30 per cent intermediate, with the provision thereof being ‘preferred’ onsite.

Funding

The Greater London Authority agreed to offer funding under the Homes for Londoners 2016-21 programme to provide homes at the Christchurch Road scheme, as defined by the Small Sites x Small Builders programme. The following funding offer was agreed, subject to the agreement of contractual terms relating to the proposed transaction:

- £1,066,666 of grant funding will be made available to the entity to which Transport for London (TfL) grants a lease to a Community Land Trust (CLT) to deliver community-led housing at Christchurch Road.

- Grant will be allocated on a pro-rata basis of £53,333 per affordable home up to a maximum of £1,066,666.

- The successful party will need to deliver an Affordable Housing tenure offer acceptable to the GLA, which is genuinely affordable to local people.

- This product must be affordable in perpetuity for future purchasers. The lease conditions must require that when the CLT sells a home, and all future residents sell on a home, they must do so at a price that is linked to local earnings.

- Funding triggers against milestones to be agreed with the GLA.

Offers were sought from Community Land Trusts only to deliver what the GLA calls ‘community-led housing’. Proposed schemes are expected to be residential-led, comprising 100 per cent affordable housing. The expectation is that all the homes built on this site will be ‘genuinely’ affordable as defined in Section 4.12 of the London Housing Strategy. This includes:

- Homes based on Social Rent levels (which includes London Affordable Rent);

- Homes for London Living Rent;

- Homes for London Shared Ownership.

TfL will only consider disposing of the site to an entity which falls within the definition contained in section 79 (1)(d) of the Housing and Regeneration Act 2008. Bids had to be submitted by 12 noon on 23 March 2018.

3. Brixton Housing Co-operative

The Brixton Housing Co-operative is a unique housing co-operative in South London. Comprising 86 homes distributed primarily in the Herne Hill Ward near Brockwell Park, additional homes are near Brixton Hill less than 1 mile from Christchurch site. Brixton Co-op has a remarkably rich history serving one of London’s most culturally diverse and vibrant communities for 40 years. Formed in the 1970s, Brixton Housing Co-op grew over the next two deacdes, but later changes in government policy and the dramatic increase in house prices halted developing by 1990. Brixton Housing Co-op is a fully mutual housing co-operative, meaning its members are both tenants and landlords, owning the co-operative collectively and responsible for managing and maintaining it as social housing landlords and part of the Co-operative Assistance Network. Its management structure is composed of a Management Committee, which is made up of volunteers from the co-operative, plus five other working groups and committees, including Membership, Maintenance, Employment and Finance, Communications and Community, and Development. Most decision-making stems from these committees and working groups, with further decision-making taken to wider general meetings. It holds annual general meetings to vote on rent increases, to appoint auditors, and to vote who sits on individual committees.

The Brixton Co-op subscribes to 7 values and principles of co-operative organisation and structure: 1) voluntary and open membership; 2) democratic member control; 3) member economic participation; 4) autonomy and independence; 5) education, training and information; 6) co-operation among co-operatives, and 7) concern for community. At its core, Brixton Housing Co-op exists to meet housing need for its community. Currently with 111 members, Brixton Housing Co-op is a culturally diverse and aging co-operative with 40 per cent of its membership BAME (of black, Asian and minority ethnicity); 38 per cent LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgendered); 80 per cent working class; 50 per cent living with HIV (the human immunodeficiency virus) or AIDS (acquired immune deficiency syndrome); 25 per cent with a physical disability; 25 per cent with diagnosed mental health conditions; 23 per cent aged 60-70; and 55 per cent aged 45-49.

Brixton Housing Co-operative is looking to address both overcrowding in some of its existing dwellings and under-occupancy in others; both of which are exacerbated by a 15 person-long waiting list. The Development Committee has addressed these issues, putting forward plans to build new dwellings as well as plans for the redevelopment of under-occupied properties. Additionally, the Committee has identified available land on which to build new homes in the London Borough of Lambeth, in order to address the changed housing requirements of present co-operative tenant members. This includes the needs, related to isolation, of older members. Working to achieve these aims for a membership of considerable size has produced innovative approaches to both governance and community engagement.

In the past, Brixton Housing Co-operative has been approached by private developers offering to include a small proportion of affordable housing units as part of their projects. However, these 2 or 3 offers have not been attractive to the co-op, would not meet the demands on its waiting list, and could contribute to the isolation of existing members. Although Brixton Housing Co-op is financially strong with a considerable reserve of capital, it is not in a financial position to acquire properties, even if private developers offered a larger block of dwellings.

4. Brixton Gardens Community Land Trust

While membership of its waiting list is currently closed due to lack of capacity, the Brixton Housing Co-op had spent over a year engaging with local residents who also value the co-operative model. Architects for Social Housing (ASH) Community Interest Company and Brixton Housing Co-operative were introduced by Co-ops for London, a grass roots organisation campaigning for more housing co-operatives in London. As a result of their ensuing collaboration, Brixton Housing Co-operative in partnership with other co-ops intended to establish Brixton Gardens Community Land Trust in order to acquire land to build more homes. The Brixton Housing Co-operative and Brixton Gardens CLT partnership identified that current Government initiatives to support community-led projects matched its desire to increase its housing stock and extend Brixton Housing Co-operative’s long history of engagement with the local community beyond its current membership to address local housing needs. This partnership aimed to build an economically diverse community of up to 27 homes, with a proportion owned by the Brixton Housing Co-operative and a proportion owned by the Brixton Gardens Community Land Trust.

Architects for Social Housing CIC intended to partner with Brixton Housing Co-operative and Brixton Gardens CLT to facilitate the community-led design work and oversee the development. The consultants comprising the development team were:

- Lead Architect and Principal Designer: Architects for Social Housing

- Project Manager: Robert Martell and Partners

- Quantity Surveyor: Robert Martell and Partners

- Structural Engineers: Tom Robertshaw Glass Limited

- Environmental Engineers: (TBC, but ideally Model Environments)

- Environmental Green Wall Consultants: Elegant Embellishments

- Renewable Energy Consultants: Brixton Energy Co-op / Repowering London

- Contractor: Black Country Make and RobsonWalsh Chartered Surveyors

- Community-led Pre-fab/Self-build Construction Team: Black Country Make

- Planning Consultant: (TBC)

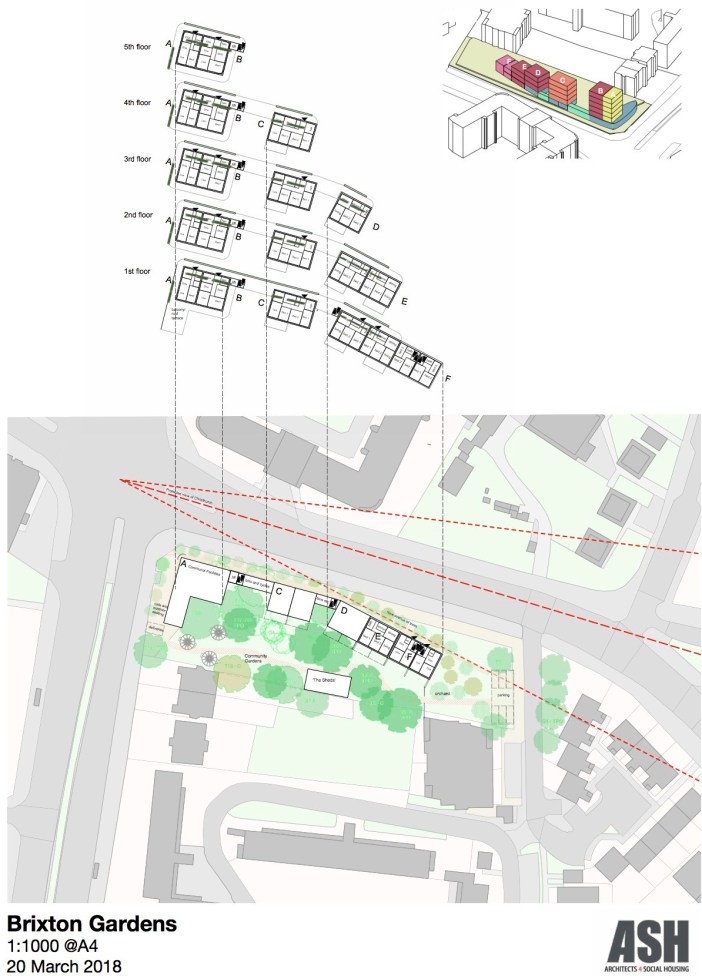

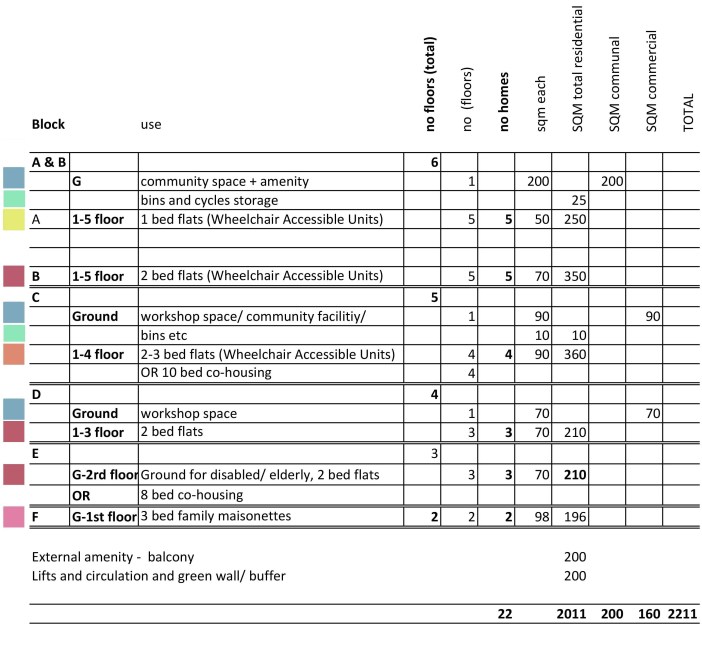

The site presented environmental challenges with its location on a busy road and along two conservation areas with restrictions including vista views. The bid set out a plan to achieve a minimum of 22 homes, a mix of 1-, 2- and 3-bedrooms, which corresponded to the maximum grant the Greater London Authority stated it would provide for the site. Our draft plans demonstrated a range of possible densities that depended on planning discussions in the future for 27 homes; but our strategies would remain the same.

The approach to construction included local job opportunities and educational and training opportunities that could be attached to Further and Higher Education for accreditation. The environmental design elements and potential ongoing educational and training throughout development responded to issues of ecology, conservation and sustainability. This included the creation of jobs via Brixton Orchard for the provision of new trees across the site, specifically along the main road to enhance the view of the Christchurch from the west. Brixton Energy Co-operative was another local partner, and would have helped develop a community micro-grid to connect all the houses and allow them to share surplus renewable energy collectively before exporting to the public distribution network.

Through Brixton Energy, the approach to construction would offer work placements on the installation of renewable energy. The aim was to get local people involved and make sure people are paid for their efforts, while taking time away from school or work to learn. The scheme would have encouraged but not make necessary Construction Scheme Certification Skills. This approach to construction would place the community at the core of the project. Young people, especially, as the future generation of green leaders, would have been encouraged to pursue pathways in sustainability and community. For this reason, via Brixton Energy, the approach would have included paid internship opportunities for local young people between 16-24 years old. Through this 40 to 50-hour internship, interns would have gained an understanding of developing and delivering community-owned, renewable-energy projects in their local area. Interns would have been asked to commit to a minimum of two hours per week, and in return be paid the London Living Wage. Throughout a typical internship programme the following would be covered:

- Solar-panel making and renewable technology (e.g. anaerobic digestion);

- Community engagement and surveying;

- Energy efficiency and home energy;

- Events management;

- Business Planning;

- Solar feasibility and project development.

Brixton Gardens CLT would be part of a strong peer-to-peer network of local community organisations and the wider co-operative community in London. This would have enabled us to locate, utilise and benefit from cross-funding opportunities as and when they become available. We would also have been able to return this benefit directly to the community, ensuring that our funding and investment strategy brought local value. To achieve this, we intended to promote a policy of local funding, aiming to ensure that procurement, at least, involved 50 per cent local content or local value addition, in order to boost economic growth and generate meaningful employment in the area.

5. Architects for Social Housing

The bid for the Christchurch Road site was made in March 2018 by the Brixton Housing Co-operative in partnership with Brixton Gardens Community Land Trust, a proposed CLT composed of members of the local Brixton community, members of the Westminster Housing Co-operative – whose homes are currently threatened with regeneration – and members of the Sanford Housing Co-operative, both of which have funds for investment. The development team, which was led by Architects for Social Housing, the lead architect and principal designer for the proposal, comprised Robert Martell and Partners as quantity surveyor, Glass Limited as structural engineers, Elegant Embellishments as consultants on the green wall, Brixton Energy Co-operative as consultants on renewable energy, and Black Country Make, a community-led, pre-fabrication and self-build construction team, with the environmental engineers to be confirmed, but potentially Model Environments, with whom ASH had worked previously.

Design and Construction Strategy

The Christchurch Road site is located on a highly prominent location at the junction of Brixton Hill and the South Circular Road. ASH’s design strategy was to address the various scales of the site, while simultaneously providing a co-operative community hub for the communities of Brixton and beyond that are struggling to find a place in the increasingly unaffordable city.

Design Proposal

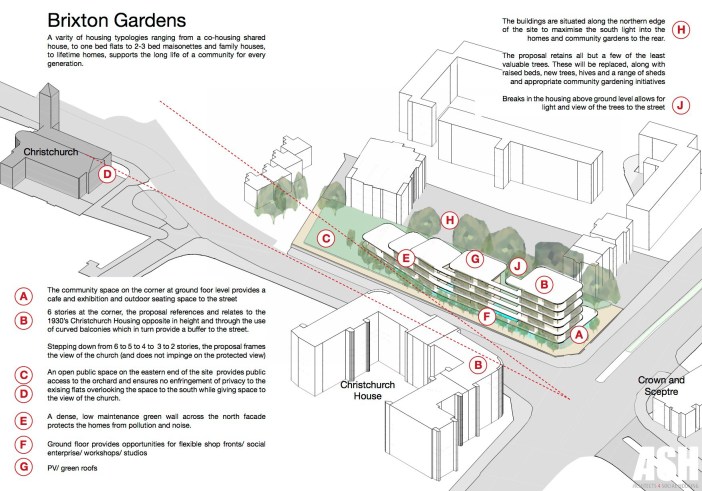

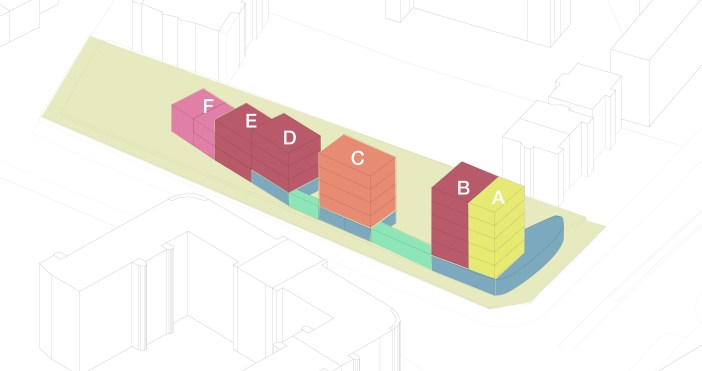

The protected view of the Christchurch was a key driver for the design of the proposal. The building we designed steps gradually down from 6 stories on the main junction – where it mirrors the 1930s Christchurch House opposite – to 5, 4, 3 and finally 2 stories in the eastern-most part of the site, and at the same time curves back from the road to frame the view of Christchurch. The tallest building, on the corner, also steps down as the road turns up Streatham hill to acknowledge the scale of the two Georgian houses directly to the south. Although the site is a busy car junction, it’s also a very busy pedestrian site, with plenty of bus routes and a bus stop right outside the site, the busy local commercial districts of Brixton hill and Streatham hill a few minutes walk away, and the Crown and Sceptre Pub opposite (frequented by Mick Jones of The Clash, who lived in Christchurch House). The introduction of a community centre here, along with flexible work and retail spaces at ground floor, responds well to the infrastructural scale of the immediate environment.

Design of Homes

ASH’s proposal located the building along the northern edge of the site, freeing up the land to the south for community gardens. All bedrooms were to be located to the south, facing onto the gardens. The north wall of the buildings and site accommodated a green buffer, access points, circulation, bath and kitchens to reduce noise and pollution in the sleeping quarters. Living spaces and balconies were also on the southern and garden side, which receives sunlight throughout the day. The whole estate was designed to accommodate a range of housing types and sizes from 1-bedroom flats to 3-bedroom homes, with a larger than necessary (+10 per cent) number of potential wheelchair and adaptable homes to accommodate the ageing population of the Brixton Housing Co-op. Homes were to be lifetime homes, zero carbon, passive house, utilizing heat exchange systems which would also ensure that air to the homes would be filtered, further reducing the effect of pollution inside the homes. The ground floor of the blocks accommodated community spaces and the potential for commercial shared workspaces, subject to local consultation.

Environmental Strategy

Environmental Strategy

The Mayor has proposed the expansion of Ultra Low Emission Zone up to the North and South Circular Roads for all vehicles from 25 October 2021. This means that the pollution on the South Circular will get even worse. To address this, the design incorporates a dense and low-maintenance Green Wall along the northern-most edge of the buildings, providing an acoustic barrier to the homes, as well as improving the air quality. The proposed design was to incorporate succulants or mosses within a concrete block design, to ensure the minimal maintenance and irrigation necessary while maximising the anti-polluting qualities of the wall. We anticipated working with research groups such as Elegant Embellishments as well as Green Wall specialists, and intended this site to be an incubator for environmentally-positive design strategies. Roofs would have incorporated Photovoltaic glass, and we would also have explored the use of ground source heat pumps.

Landscape and Communal Gardens

All significant trees on the site would have been retained. Any trees classified as U, in such a condition that they cannot realistically be retained as living trees in the context of the current land use for longer than 10 years, would have been cut down and replaced, and a new tree lined avenue would have been planted along the northern edge of the site. A new public amenity space was to be provided along with some parking provision to the east of the site, ensuring there would be no overlooking of the existing housing along the south-eastern edge of the site. Brixton Orchard agreed to be our partner in the provision of new trees across the site, and particularly along the main road, in order to enhance the view of Christchurch from the west. These would specifically have included silver birch trees. According to a study from the University of Lancaster published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, silver birches can absorb as much as 50 per cent of the particulate matter generated by automobiles. Raised beds would have accommodated community gardening or allotments, in order to address the issues of contamination in the soil; and sheds located in the community gardens would have provided gardening or workshop training facilities as well as a tool library.

Community-led Construction Strategy

In partnership with a modular, pre-fabricated, structural manufacturer such as Black Country Make (BCM), the aim was to accommodate self-build where possible, enabling apprenticeships and training schemes as well as lowering the costs of construction. The proposed construction methods would have a minimum 60-year design life for the structure and weather-proofing of the building, and would be fully compliant with all relevant Building Regulations. We would work with an organisation like BCM to:

- Develop a modular ‘in the community’ approach, with minimal set-up cost;

- Build very high-performance homes for no cost premium;

- Address energy poverty;

- Enable 100 per cent local training and employment schemes with entry-level ‘work ‘n’ learn’ on the job;

- Exploit the modular approach, reducing build costs and waste and the capacity to scale without losing quality;

- Allow people of all abilities to have open access to the tools and knowledge in design, assembly and build;

- Keep the supply chain local to the community, capturing value and impact in the local economy;

- Reinvest all profits for the benefit of the local community, thereby delivering a new civic economy;

- Leave the knowledge and tools in the hands of the community to continue and expand community-led housing and development.

Project Programme

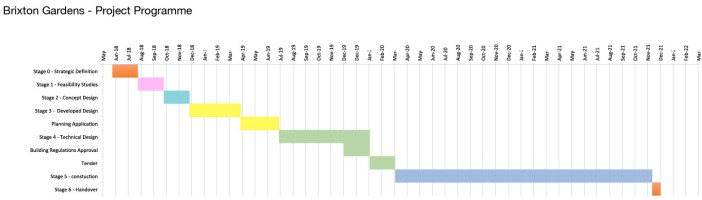

The projected timeline for the development of the scheme was as follows:

Project Cost

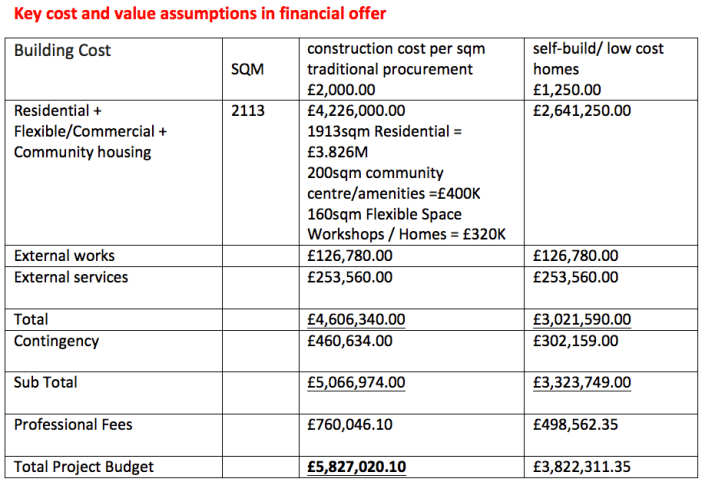

In order to be able to assess the value of our project, ASH, Brixton Housing Co-op and Robert Martell and Partners explored two construction options for the proposed scheme, traditional and self-build, and their relative costs.

Through this collaboration with members of Co-ops for London, Sanford Housing Co-op, Westminster Housing Co-op and Brixton Housing Co-op, it became apparent that housing co-operatives often have considerable financial capital, which potentially could be used to fund new developments. The creation of the Brixton Gardens CLT, composed of co-operatives, would have produced a particular form of CLT that doesn’t currently exist. The homes developed by Community Land Trusts are typically properties for sale, which is not the housing type in greatest demand in London. By contrast, housing co-operatives are composed of low-cost rental accommodation, the tenancy type in most demand. We were aware that the CLT structure required by the bid for the Christchurch site had a presumption in favour of building homes for sale. However, all the partners in the Brixton Gardens CLT were adamant that we were only interested in providing homes for social rent. The Brixton Gardens CLT could potentially have galvanised co-operative value within a CLT structure, making the best of each organisational structure: co-operative as the form of management; community land trust as the form of land ownership.

6. Community-led Housing

On 18 June 2018 it was announced that the ASH/Brixton Housing Co-op proposal had been rejected in favour of the winning proposal. This has been made by the London Community Land Trust, which had won the contract not only for the Christchurch Road site in Streatham but also for the Cable Street site in Tower Hamlets. Unlike the Brixton Housing Co-op, whose members are long-term residents of the area, the London CLT appears to have no local connection to either site, which raises the question of what community was leading the winning proposal. Nor does it appear that London CLT has put any architectural proposal forward of what their development will look like.

It subsequently emerged that the deciding factor in awarding the land was the price London CLT offered for it to Transport for London. It is unclear how a proposal can be described as ‘community led’ if its selection above competing proposals is dependent upon the financial means of the bidders. Should publicly-owned land, such as that held by Transport for London, be subject to the same commercial forces as privately-owned land; and if it is, in what way can the scheme built on it be said to be community-led? Since any commercial bid for land will be dependent upon what is built on it, with the higher proportion of homes for either shared ownership, rent to buy and market sale generating higher profits, how is selecting a proposal on financial criteria meant to encourage the provision of more affordable housing for social rent, the housing tenancy in most demand in London? As it turned out, the ‘affordable housing’ the London CLT is planning to build on the site will, in fact, be 100 per cent homes for sale, and will therefore deliver property for middle-income earners that is further subsidised by Help to Buy funding. In a press release London CLT stated:

‘The CLT homes will be sold at a price set according to average local incomes. The price is based on the principle that no one should spend more than a third of their income on their home, which means the homes cost less than half the price of similar homes on the open market. Residents sign a contract promising to sell on the home at a price linked to incomes in the area, so CLT homes remain affordable not just for the first residents, but for future generations.’

Since the average price for property in Christchurch Road stood at £327,281 in January 2019, and new-builds are likely to be even higher, it’s difficult to see how this responds to housing need in Streatham; or how this comes anywhere near Lambeth council’s Local Plan target of 70 per cent homes for social rent and 30 per cent intermediate.

In contrast, the ASH/Brixton Housing Co-op bid had 100 per cent homes for social rent. Moreover, our bid was designed to provide the highest number of homes for social rent within the financial constraints of the project. If it had been made clear that the highest financial bid would win the site, we could have proposed alternative financial models based on a higher proportion of homes for London Shared Ownership or London Living Rent. That said, we don’t believe that public land made available for the provision of affordable housing should be subject to competitive tenders selected simply on how much profit they will make for Transport for London or other landlords. On the contrary, we believe public land should be made available for the public good, which is to supply the homes in which Londoners can afford to live.

We also believe that, in order to earn the definition of ‘community-led’, a proposal should be made by the community that will live in it, that they have had a hand in developing it, and that the community has a connection to the area. Given that the members of the Brixton Housing Co-op are predominantly BAME and LGBT, the proximity of the site to Brixton makes it ideal to their inhabitation in the homes they wish to build there, in a way that, for example, the other site made available by TfL in north-west London was not. Yet none of this appears to have played any part in the awarding of the site to a London-wide CLT with no links to the area. Again, what does ‘community-led’ mean in the context of the GLA’s decision to reject an offer from a housing co-operative with nearly half a century of history in the local area and in desperate need of more homes for its Brixton-based community?

These questions are in no respect meant to cast aspersions on the London CLT, whose commitment to building community-led housing we support. What we would like is further guidance from the GLA on what ‘community-led’ means in practice; to know how it constrains bids and what role – if any – it plays in the assessment of bids for land. We suggest that the offers made could have a range of options, laying out the financial viability of the scheme according to the different proportion and types of affordable and social housing. And given the fewer resources available to smaller housing co-operatives and architectural practices, we would like a longer time to prepare a bid than the mere 2 months allotted between the announcement of the Small Sites x Small Builders in January 2018 and the deadline that March, which greatly benefited the bids of larger developers. As it was, ASH and Brixton Housing Co-op had less than a month to produce the documentation for the bid, including the architectural designs.

We would also like to see the definition of ‘community-led’ in the Resource and Advice Hub website brought closer to what it means to the communities seeking land on which to develop co-operative housing schemes, and not be used as a facade for competitive tender between property developers. To this end, we would like to see community-led housing defined not by ‘shared principles’ and ‘presumptions’, but by required practices and outcomes. As currently defined, principles like ‘community engagement and consent’ are drawn straight from the Mayor’s Good Practice Guide to Estate Regeneration, and require no more than industry-standard practices of resident consultation that have been shown time and again to be little more than exercises in public relations; while requiring the ‘community-led’ development to bring ‘benefits to the local area’ does little more than a Section 106 agreement with the developer. In particular, the GLA’s statement that one of the benefits of community led housing is ‘a greater sense of ownership’ is incompatible with both the housing needs and the financial means of the more than 27,000 people on Lambeth council’s housing waiting list, and who are waiting for council homes for social rent. In the Consultation Report published by Lambeth council in 2017 it specifically states: ‘There is a very high level of affordable housing need in Lambeth, with a particular need for rented accommodation for those on the lowest incomes.’

A report titled From Right to Buy to Buy to Let, which was published this month by the London Assembly, revealed that at least 36 per cent of London council homes sold at a discount through the Right to Buy are now being rented out at market rates by private landlords, with 2,333 of these properties being rented back to the councils that sold them in order to house their homeless constituents. While we fully support the call to revoke this scheme that has transferred such vast quantities of both public assets and the funds to pay their increased rents into private hands, selling off London’s limited stock of public land to developers – whether community land trusts or otherwise – in order to build properties for sale is contributing to the same loss of the much needed homes for social rent that could have been built on such land. What we would like to see, therefore, is an assessment of the social value of any bid for land made a primary factor in the decision-making process, rather than the overriding and decisive factor being the increased financial value of the land generated by the new development. In other words, we would like to see land allocation made in accordance with housing need.

Above all, we would like to see more London boroughs release more land to similar initiatives. To this end, we propose a forum with the relevant representatives of the Greater London Authority, Transport for London and London Councils in which London’s housing co-operatives will be able to give feedback on this pilot scheme, Small Sites x Small Builders. We would like to see this scheme repeated, but also improved and extended, so that proposals for genuinely ‘community-led housing’ can find the land housing co-operatives need to build the homes in which Londoners present and future can afford to live.

Architects for Social Housing

Brixton Housing Cooperative

Architects for Social Housing is a Community Interest Company (no. 10383452). Although we do occasionally receive minimal fees for our design work, the majority of what we do is unpaid and we have no source of public funding. If you would like to support our work financially, please make a donation through PayPal:

Reblogged this on Anarchy by the Sea!.

LikeLike

Good point: “…In order to earn the definition of ‘community-led’, a proposal should be made by the community that will live in it, that they have had a hand in developing it, and that the community has a connection to the area…”

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Wessex Solidarity.

LikeLike