ASH Presentation to the Architectural League of New York (Part Two)

One of the key ways in which ASH is responding to this threat to our social housing is through the production of architectural alternatives to estate demolition through designs for infill, roof extensions and refurbishment that increase the housing capacity on the estates and renovate the existing homes while leaving the communities they house intact.

Residents from West Ken and Gibbs Green estates in West London have been fighting for 7 years against the demolition of their homes by the developer CAPCO as part of their £1.2billion earls court development. In September of last year, ASH was approached by the residents of the estates to do a feasibility study for additional homes and community facilities, and refurbishment to the existing homes and improvements to the existing landscape. This feasibility study is the basis of the residents’ current application for the right to transfer the estates from the local council into their own ownership and management.

West Kensington And Gibbs Green is comprised of two neighbouring estates of 730 homes for around 2000 residents. Architecturally they are composed of a diverse range of building types from 4 bed family houses with gardens, to medium rise two-storey maisonettes around communal courtyards and one and two bed flats in 10-12-storey towers.

Over the following months, ASH conducted a series of six design workshops attended by around 200 residents overall. These were set up in order to get to know the residents and the estate, and to understand what the residents wanted to see happen there.

As the consultation progressed, these workshops also allowed us to use a diverse range of media to draw and test ideas with the residents. We also communicated issues like planning and other constraints, as well as our own design ideas, so that they could get an understanding of the process, and a genuine picture of the options available to them.

ASH took all the information we obtained during the course of these workshops and located the comments on a giant map that was to grow and grow as our knowledge increased, and the project unfolded: green for things they liked, red for things they didn’t like, and blue for solutions and opportunities.

In addition to these workshops, we also organised a series of evening resident led walks about the estates.

As part of these walks we arranged to visit inside residents’ homes to get an understanding of each of the typical layouts and how they worked. It was also an opportunity to get to know the residents better, and to hear them talk about what their homes mean to them and how much they love living there. This revealed one of the key issues at the heart of the current problem – namely, that these are people’s homes that are being destroyed.

Homes that are not simply units for sale or investment.

Homes that are anything but the generic poverty traps we are presented with in the press.

Homes that are not simply commodities to be exchanged.

But well-loved places of memory and experience.

From the walks and information gathered during the course of the consultation events, ASH started to draw what we were beginning to understand: the routes residents took through the estate.

And the boundaries we encountered.

Finally we produced a map that located all the places which the residents and ASH had identified as locations for improvements, infill or roof extensions.

Our final design proposes around 250-330 new homes on the estate. This includes infill housing, shown in yellow, and roof extensions, shown in pink. In addition to new flats we designed new community facilities, single-storey disabled or elderly housing, and new townhouses for larger families. We also designed improvements to the landscape, such as new and improved play areas, and an increased biodiversity across the whole site. Refurbishments to the existing blocks included winter gardens to the towers (with an increase of around 15 square metres on existing studio flats) as well as improved insulation and ventilation strategies, plus renewable energy sources.

ASH produced specific designs for each site we identified, and we exhibited these designs last December to a room of around 60 residents who both helped present and commented on the proposals. Here we can see proposals for infill housing and two floors of roof extensions in Gibbs Green.

And here we can see the designs for the winter gardens and roof extensions to the tower blocks and to the existing lower maisonettes (to the right) with new west-facing roof gardens.

Beside a renovated playground, ASH proposed new single-storey housing for elderly and disabled residents who are either downsizing or in need of supported accommodation. This could in turn free up the larger homes for families that are currently living in overcrowded accommodation elsewhere on the estate. ASH proposed that some of the currently under-used garages could be converted to workshops that could provide some income for the estate, low cost workspaces for residents, and would also contribute to the social qualities of this outdoor space.

ASH proposed a new infill block adjacent to an existing tower. This has a new community space on the ground floor that could open up to Franklin Square for community events.

This is the largest of the new infill sites providing around 60 new flats of a range of sizes built on the site of the previous single-storey community hall – which is relocated. This set of buildings is built around a new public space, and provides a new entrance to the estate from the south.

The project has been costed, and a viability assessment produced. ASH is confident that the rent or sale of a proportion of these new homes will enable all the existing homes to be refurbished and all the proposed improvements to the landscape to take place.

ASH’s model of the estate proposals now remains with the residents who use it to describe the project to visitors, in this case Green Party Mayoral candidate Sian Berry, who has been very supportive of the project.

Residents from Central Hill Estate in the borough of Lambeth, South London, approached us in May 2015, following the announcement by the local authority of their desire to demolish their homes. Although in many cases residents are promised brand new homes at the same rent on the new redevelopment, the reality is that in almost every case, rents increase, and even those lucky enough to be rehoused, or who have survived 10 years on a building site, often find themselves struggling financially as a result. In a recent report, the Joseph Rowntree foundation showed that existing residents are typically worse off as a result of estate regeneration schemes.

In the case of the Heygate Estate, also in south London in the adjoining borough of Southwark, residents were forced out of their homes which had been sold to the developer Lend lease to make way for the demolition and rebuilding of 2704 new homes, of which only 82 are to be for social rent. In the new Trafalgar place development – one of the first developments on the demolished estate – which was in fact nominated for this year’s Stirling Prize (a nomination ASH protested against) – a 2-bedroom flat is now going for £725,000. As you can see from the maps, the residents, both homeowners and tenants alike had to move miles away from their homes to be able to find somewhere they could afford to live.

In the case of the Heygate Estate, also in south London in the adjoining borough of Southwark, residents were forced out of their homes which had been sold to the developer Lend lease to make way for the demolition and rebuilding of 2704 new homes, of which only 82 are to be for social rent. In the new Trafalgar place development – one of the first developments on the demolished estate – which was in fact nominated for this year’s Stirling Prize (a nomination ASH protested against) – a 2-bedroom flat is now going for £725,000. As you can see from the maps, the residents, both homeowners and tenants alike had to move miles away from their homes to be able to find somewhere they could afford to live.

The managed decline of these housing estates by local authorities, is cited by those same authorities as proof that is no other alternative to demolition. Their subsequent demonization as places of crime and antisocial behavior by the media, leads to the wider cultural acceptance of their demolition among the general public. Both of these assumptions are fundamentally untrue, and are deliberately masking deeper problems of poverty and austerity, which are in fact only being exacerbated through demolition projects such as this. To the left is an image tweeted by the local councilor and cabinet member for housing, claiming that mold is one of the reasons the estate must be demolished. To the right an image tweeted by PRP, the local authority’s architect, accompanied with the question ‘Would you walk down this alleyway?’ Here is ASH’s alternative narrative confronting the propaganda of estate demolition with the reality of estate living.

These last few slides were taken at an event ASH organised called Open Garden Estates, in which a dozen estates across London took part this year. This was an event designed to challenge the negative propaganda around council estates, as well as provide residents with an opportunity to organise their campaigns, and make contact with other estates in similar situations.

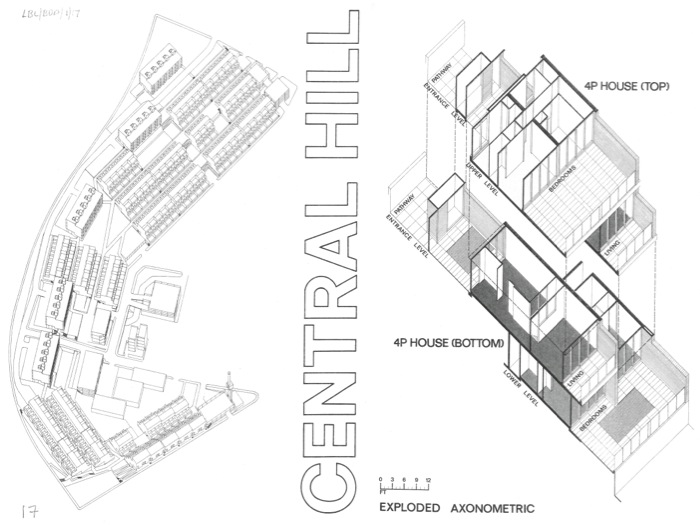

Central Hill Estate was designed around the existing trees and landscape, and is made up of pedestrian ‘ways’ off which pairs of stacked maisonettes are arranged over the hillside, with every home having a view of London to the north, and a courtyard to the south.

Central Hill is an estate of 456 homes, ranging from studios to 6-bedroom houses.

All of which are currently threatened with total demolition.

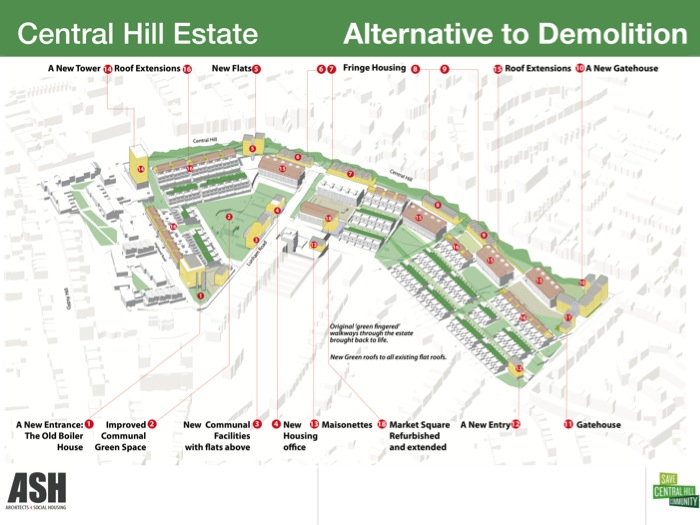

In contrast to this, ASH’s proposal retains and refurbishes all the existing homes, keeps as many of the existing trees as possible, while making improvements to the landscape and community facilities, all paid for by the rent or sale of a proportion of the new homes.

ASH’s proposal identifies the possibility for over 200 new homes on Central Hill estate. Infill housing in yellow occupies unused and derelict sites around the edges of the estate. Roof extensions, in pink, consists of one or two additional floors on top of some of the existing flats around the edges of the estate where they do not obscure any views. These would be lightweight prefabricated construction, craned into position.

Site 1 identifies the existing boiler house as a potential site for an infill development, and a new entrance to the estate, where we could build a new 7-storey block of 28 flats above workshops or other commercial spaces below. Architecturally this retains the chimneys, which are a significant part of the history of the site. Thriving cities are built up in layers over time, cultivating memories, and enabling the growth of their communities, not erased every few decades. On Sites 3 and 4 ASH are proposing to demolish the existing single story community centre to free up more green open space, and re-provide the community facilities on the ground floor of a new building forming a new urban edge to the adjacent street.

All around the edges of the estate, we have added new housing that addresses both the estate, and the neighbouring streets, knitting the estate into the surroundings. Lining the main road at the top of the hill, we propose strips of 2-storey housing which sits above an underused access road, and makes a new façade for the estate. This also provides some disabled access housing and improved access into the estate, which has been identified as a problem by the residents.

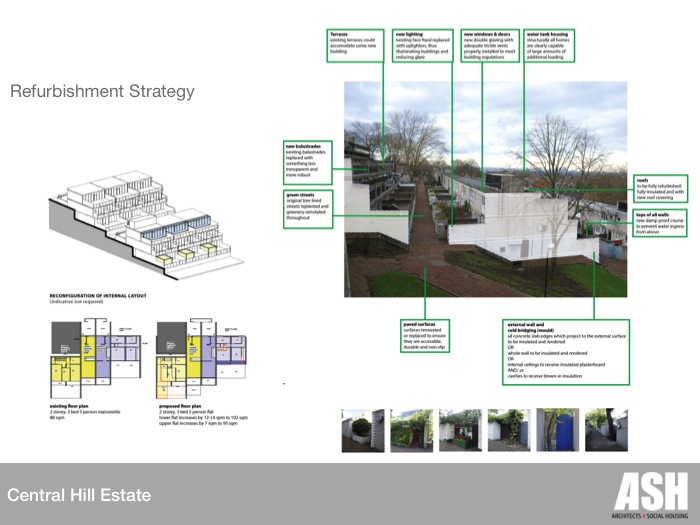

ASH is collaborating with a sustainable energy consultant who is currently doing a calculation for the amount of embodied carbon in the existing homes. We have been told that it would take around 60 years for a new more energy efficient building to pay off the environmental costs of demolition. If this is the case, given the often poor quality of replacement housing, its unlikely that what is going to be built in its place will be there that long. We also explored the refurbishment of the existing homes, in particular the possibilty of extending the homes horizontally on the existing terraces.

We have had our scheme costed by a quantity surveyor, who calculated that the construction of 220 new homes and new community facilities comes to around £75 million. Lambeth Council’s own surveyor has evaluated the cost of refurbishment of the existing homes as around £12 million, or £18 million if we include internal refurbishments, which has been funded by the government’s Decent Homes programme. This comes to a grand total of £93 million. If we assume a similar cost per square metre, not taking into account the highly complex site conditions, which necessitated one of the most expensive estate projects of its time, or the costs of demolition, the notional cost of simply rebuilding the existing 456 homes would come to over £100 million. And that’s before a single new home has been built.

ASH believes that our proposal is the most socially, environmentally and financially viable future for Central Hill Estate, respecting the existing environment, homes, and community.  The city is a palimpsest of its making, and the erasure of its history is always an ideological act. Architects are happy to talk about how to build our way out of the housing crisis, but we are less willing to engage with the fact that estate demolition – and our own role in it – is one of the forces driving this so-called crisis. If architects are going to have a meaningful role to play in the future of our cities, we have to start establishing our priorities, challenging the rhetoric about the housing crisis, questioning our own role in current housing policy, and, like our forbears, contributing to a vision of the social housing of the future. Architecture is always political.

The city is a palimpsest of its making, and the erasure of its history is always an ideological act. Architects are happy to talk about how to build our way out of the housing crisis, but we are less willing to engage with the fact that estate demolition – and our own role in it – is one of the forces driving this so-called crisis. If architects are going to have a meaningful role to play in the future of our cities, we have to start establishing our priorities, challenging the rhetoric about the housing crisis, questioning our own role in current housing policy, and, like our forbears, contributing to a vision of the social housing of the future. Architecture is always political.

Geraldine Dening

Architects for Social Housing