I wrote the basis of this text in December 2020, when I was reading The Lord of the Rings aloud to my girlfriend every night, partly as a way of wiping our minds clear of the violence and absurdities of life under lockdown before we plunged into a hopefully forgetful sleep. But I think the text originated in an online discussion on some social media forum or other about Peter Jackson’s films of Tolkien’s book, which I like less and less and cannot watch now for more than a few minutes without shouting at the screen. In response to my main thesis, which is about the relationship between Frodo and Sam, I was accused by others on the forum of trying to ‘woke’ Tolkien — which, given my longstanding criticisms of woke, was a turnaround for the books. But I could understand their concerns. The official Tolkien Society has in recent years utterly betrayed Tolkien by collaborating in woke’s attack on his work, which has culminated — thus far — in Amazon’s risible and widely-condemned television series, The Rings of Power. In 2021, for example, The Tolkien Society’s Summer Seminar asked contributors to submit papers that ‘consider the role that diversity plays in Middle Earth’. This brought forth such risible titles as ‘Gondor in Transition: A Brief Introduction to Transgender Realities in The Lord of the Rings’, ‘The Invisible Other: Tolkien’s Dwarf-Women and the “Feminine Lack”’, and ‘“Something Mighty Queer”: Destabilizing Cishetero Amatonormativity in the Works of Tolkien.’

I only bring this up here to make it clear that I distance myself from this ‘critical’ approach — if one can describe woke’s obediently repeated orthodoxies and tortuous terminology as such — and that I would never submit my own (reworked) text to an organisation that provides a platform for this ideology, which hates everything the author of The Lord of the Rings held sacred. That isn’t to say that I share all of Tolkien’s values — far from it; but I have read his books since I was a child and continue to do so, strange as that may seem to the readers of my own books, and I have often wanted to write something about what I think of his work. This is very different from how it is dismissed, on the one hand, by the gatekeepers of English Literature as stories for children, or transformed, on the other hand, into ‘fantasy’ fiction by the US culture industry of which the films and television series are consumer products. What I think of Tolkien’s books is beyond the parameters of this short article; but one day, perhaps, I will write a book about them, before a new generation is brought up to hate and dismiss Tolkien with the certainty and stupidity of woke.* It is, however, in the context of this anti-English ideology and its almost total colonisation of every aspect of our culture that I publish this article now — if only, perhaps, to demonstrate that it is possible to write about identity, culture, history, nationality and even sexuality without becoming the mouthpiece of woke’s hatred for everything English. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

* * * * *

‘They may be irritated or aggrieved by the tone of many of my criticisms. If so, I am sorry (although not surprised). But I would ask them to make an effort of imagination sufficient to understand the irritation (and on occasion the resentment) of an author who finds, increasingly as he proceeds, his work treated as it would seem carelessly in general, in places recklessly, and with no evident signs of any appreciation of what it is all about. . . . The canons of narrative art in any medium cannot be wholly different; and the failure of poor films is often precisely in exaggeration, and in the intrusion of unwarranted matter owing to not perceiving where the core of the original lies.’

— J. R. R. Tolkien, Letter to Forrest J. Ackerman (June 1958)

I’m not going to talk about the narrative role of Hobbits as the protagonists through which Middle Earth is discovered by the reader of Tolkien’s books as they take us from the relative familiarity of The Shire to the darkness of the increasingly familiar Mordor, but about their culture.

I’ve been watching a number of YouTube videos recently in which Tolkien scholars discuss various aspects of the ‘legendarium’ (as the secondary world he created is now called), and it’s struck me that, since Peter Jackson’s films came out, the hitherto wide variety of interpretations of what Tolkien’s world and the people in it look like has been reduced to imitations of Jackson’s vision. In my opinion this is unfortunate, as although Jackson’s films have their qualities (less so his almost unwatchable rewriting of The Hobbit), his understanding of Tolkien’s world is fundamentally wrong. This is nowhere more evident than in his depiction of Hobbits.

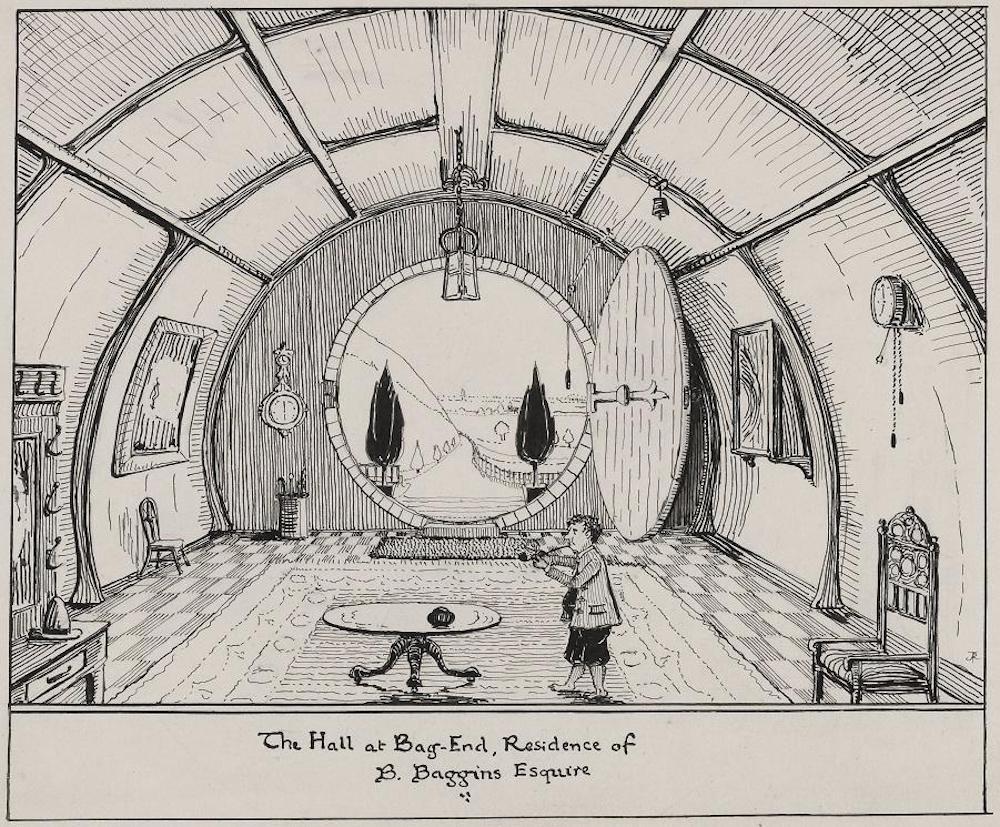

One of the artists who had the most influence on the appearance of Hobbiton in the films was the Canadian illustrator, John Howe, whose depictions of Tolkien’s world I like, but who has lived most of his life, and all of it as a Tolkien illustrator, in Switzerland. And it shows. His depictions of the interiors of Bag End, in particular, are clearly influenced by the alpine architecture of his adopted homeland, and bear little resemblance to the very English look of Tolkien’s own drawings, for instance in the final drawing reproduced in The Hobbit titled: ‘The Hall at Bag-End, Residence of B. Baggins Esquire.’

Tolkien, by his own admission, had no facility for depicting figures, from which much of the confusion about Hobbits comes; but he was rather good, and very accurate, at depicting landscapes and places both textually and visually. Reading The Lord of the Rings for the umpteenth time, I’ve been struck by the detail and particularity in Tolkien’s descriptions of all the different buildings and structures in the story, from Buckland to Bree and Rivendell, Khazad-dûm and Caras Galadhon, Helm’s Deep and Orthanc, Minas Tirith and the Tower of Cirith Ungol. So I’d say this drawing of Bag End is both particular and accurate, and round doors aside it’s unlike either Howe’s or Jackson’s depictions of it.

I’ve never been to New Zealand, where Jackson’s trilogy was filmed, but the first time I arrived in Australia back in the 1980s I was struck by how unfinished everything is there compared to England. Our landscape is the product of thousands of years of animal husbandry, agriculture and town-planning; Australia’s vast spaces have been subjected to the same for about two-hundred years, and New Zealand’s for even less. Roads are hastily laid over clumsily-cleared land, and often have no kerb. Mile after mile of barbed-wire fences divide uncultivated fields. Flora is untended and semi-wild. Grass is uncropped. Ponds are stagnant ‘billabongs’. Rivers brown and unbanked. And the distinction between urban development and what Australasians call ‘the bush’ is uncertain and changing. I have considerable admiration for Jackson’s realisation of the world of Middle Earth — by far the best part of his otherwise Hollywood-vision of the story; but when I first saw Jackson’s recreation of Hobbiton on a sheep farm in Waikatoo, I was struck by how unlike its neglected appearance was to Tolkien’s depiction in the books, which is drawn from the gentle countryside and well-ordered villages, crop-planted fields, sheep-cropped grass and hedgerow-lined roads of the rural England of his childhood in Sarehole, Worcestershire.

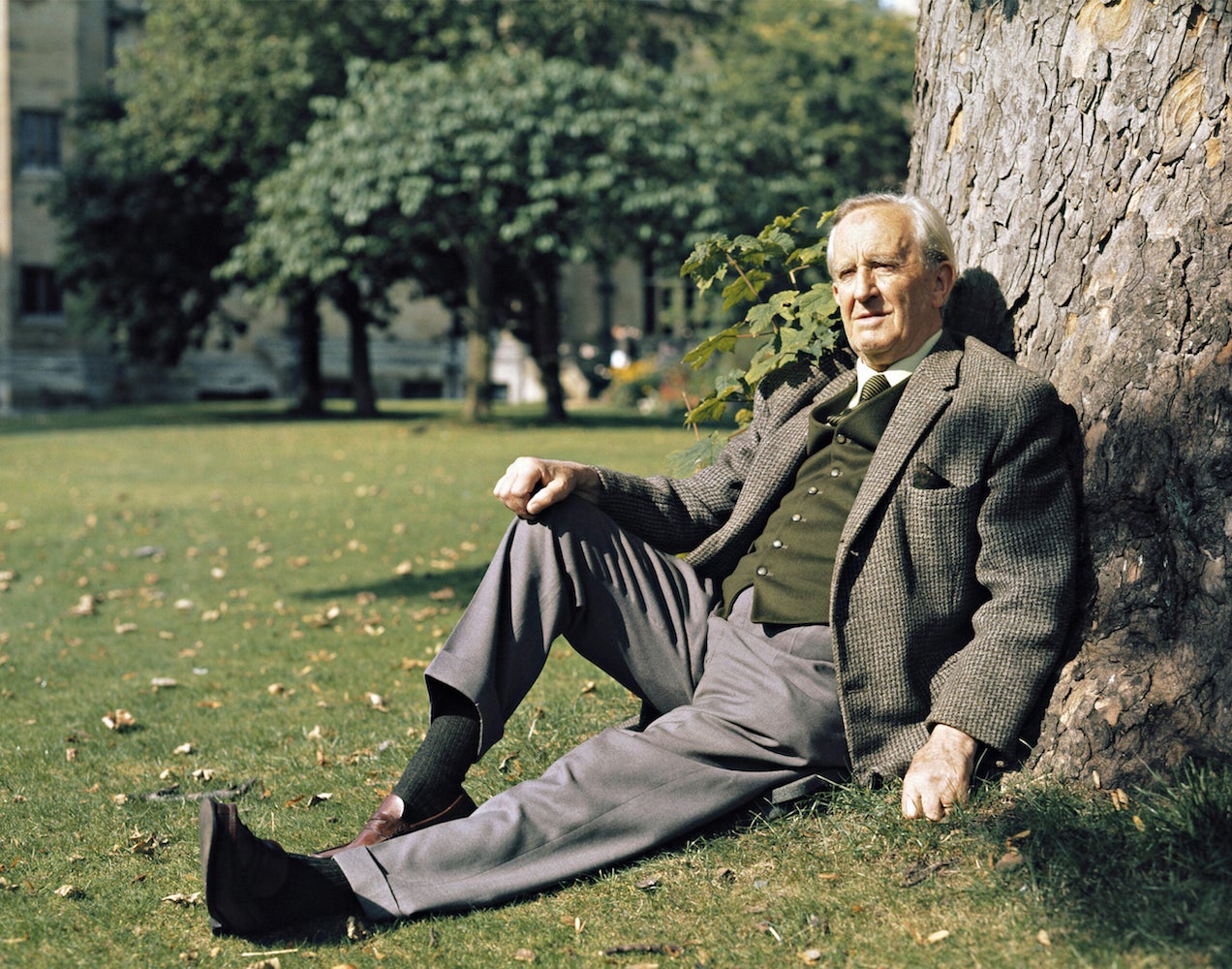

And the same applies to Jackson’s Hobbits themselves. First of all, I don’t know where the costume department got those baggy, three-quarter-length trousers from, the sort you might find in brighter colours on Bondi Beach today, or those loose-hanging, sleeveless coats; but Hobbits dress in breeches, which were standard country clothing in nineteenth-century England, that fitted closely just below the knee, where they were buttoned at the side, and waistcoats, very much like the ones Tolkien wears in almost every photograph of him. They also dress in the bright colours of medieval fashion — as Tolkien writes in ‘Concerning Hobbits’, chiefly yellow and green — not the muddy browns of Jackson’s Hobbits. And although their hair is curly, they don’t have the 70s rock-star hairdos sported by the actors in the films, who sometimes resemble a heavy-metal band from Birmingham that never made the final cut of This Is Spinal Tap.

Tolkien, as his name indicates, was of German extraction, and it was the Norse myths, above all — The Saga of the Volsungs and its like — that most informed his secondary world. The task he set himself, however — which was to create a mythology for his beloved England, whose myths had been erased by the Norman conquest — was part of the Celtic Revival and its Romantic vision of the past, which merged the norms of nineteenth century Britain with a largely imaginary vision of the Dark Ages. This, and not the ‘fantasy’ tropes of US consumer culture, is the cultural ground from which Hobbits, Dwarves, Elves, Wizards, Goblins, Trolls, Wargs, Ringwraiths, Balrogs and Dragons grew in Tolkien’s fertile imagination.

Far more important than the appearance of Hobbits, however, is Jackson’s complete incomprehension of their characters, behaviours and relationships. Frodo Baggins, esquire, is an English gentleman in wealth, manners and speech. During the War of the Ring, he’s 50 years old. Hobbits live a little longer than humans and mature a little later, but not by much; yet to attract the US film-market, Jackson cast the 18-year-old American actor, Elijah Wood, to play him in the film. He does the best he can for a teenager, but he’s nothing like the middle-aged Frodo, who refers to Sam as ‘my lad’, and is treated by the other Hobbits as their elder and better. Meriadoc Brandybuck and Peregrin Took, in contrast, are both aristocrats, from old families even wealthier than the Bagginses (although not as respectable), and their behaviour and speech is that of young (Merry is 36, Pippin, who hasn’t ‘come of age’, is 28), very privileged men — to the manor born, as we say in England — who have never done a day’s work in their life and never will. Both address Sam, who is older than they (38), by his first name, while he, by contrast, addresses them as Mr. or Master.

As a demonstration of these class distinctions and how they determine their relationships with each other, when the Hobbits arrive at the farm of Farmer Maggot (‘A Short Cut to Mushrooms’) the latter, as a land-owning farmer, addresses the two gentlemen as Mr. Peregrin and Mr. Frodo, using their given names, while they address him, as their social inferior, as Mr. Maggot, using his surname. Sam, as Frodo’s gardener and what Aragorn openly refers to as his ‘servant’, isn’t introduced or addressed in the whole conversation. For Mr. Maggot, Sam was the equivalent of the workers ‘belonging to the farm-household’ who join them later for supper. When the New Zealand writers of the films have Aragorn reply to Sam’s query about where he’s leading them from Bree with ‘To Rivendell, Master Gamgee’, they not only depart from Tolkien’s text but also from everything he tells us about Sam and the source of his devotion to his master, Mr. Frodo Baggins. This was all common practice within the class system in which Tolkien grew up and lived in England. And as commentators have remarked, this is the analogue for The Shire, and why, in Tolkien’s drawing of Bag End, there are nineteenth-century anomalies like a wall clock, barometer and umbrellas in a world otherwise set in the technology of the Dark Ages.

But it’s when it comes to the absolutely key relationship between Frodo and Sam that Jackson’s film goes so badly wrong. As a Kiwi, he can’t be blamed for having as little understanding of English class relations as he does the English countryside, but he could have done a little research. As anyone who has read Evelyn Waugh’s contemporaneous Brideshead Revisited — or more likely seen the television adaptation — will know, when a young member of the British upper-middle-class arrived at Oxford or Cambridge in Tolkien’s time he was assigned a ‘Scout’ to fulfil the functions of the male servants he left at home. Like clerks in British legal practices, these were drawn exclusively from the working class. Tolkien would undoubtedly have had one of these as a young man and student at Oxford University.

Even more intimately, when Tolkien, after graduating, served as a junior lieutenant on the Western Front during the Great War, he would have had an equivalent ‘Batman’, a soldier-servant who acted as his runner, valet and bodyguard, just as Sam does for Frodo. It’s well documented — and attested to by Tolkien himself in his letters — that this imposed intimacy in the face of the horrors of trench warfare led to a greater knowledge and perhaps appreciation of the millions of working-class soldiers by the young toffs whose fathers sent them to their deaths. As Frodo and Sam make their steady progression into the horrors of Mordor — much of whose description is drawn from the battlefields of the Somme, with Sam eventually carrying Frodo on his back up Mount Doom — the deep affection between them, while retaining the formality of their huge class divide, is drawn from these experiences. In a letter to H. Cotton Minchin dated April 1956, Tolkien wrote: ‘My Samwise is indeed a reflection of the English soldier . . . of the privates and my batman that I knew in the 1914 War, and recognised as so far superior to myself.’

In contrast, Jackson plays Frodo and Sam’s relationship like an American buddy movie, a fantasy version of Stand by Me, with Merry and Pippin, played by British actors (a Scottish Pippin and a Northern Merry), dressed and acting and sounding like farmer’s hands (‘Welcome, my lords, to Isengard!’) rather than landed aristocracy and heirs to the wealth of their old families, the Tooks and the Brandybucks. It’s the realisation of their expectation of coming into that inheritance and the continuation of their respective families’ authority that Pippin eventually becomes the Thain of the Shire and Merry the Master of Buckland — and not, as they are depicted in the film, the reluctant and unappreciated heroes of Hollywood narrative cinema having a quiet pint in the Green Dragon Inn, Bywater.

Why is this important? I can understand that few of the millions of contemporary viewers of Jackson’s films have much interest in the subtleties and contradictions of the English class system a hundred years ago as viewed by an Oxford don and veteran of the Great War, but it’s on these values that Tolkien’s world is built. It’s always struck me that not only are Merry and Pippin both aristocrats, but that every other member of the Company of the Ring are too. Legolas is a Sindarin Prince; Gimli is a member of the royal family of Durin; Boromir is the first son of the Steward of Gondor; Aragorn is a Númenórean king in waiting; and Gandalf is a member of the angelic order of the Maiar. Apart from Ugluk, Grishnakh and the handful of other orcs allowed to speak, only Samwise Gamgee, to give him his full name, speaks for the working class. And in the appendices we learn that, at the age of 47, he is elected Mayor of the Shire, which is as much social advancement that a gardener could hope to achieve. His unshakeable servility sticks in my craw, as I’m sure it does many other readers today; but he is, as Tolkien wrote to Milton Waldman, the ‘chief hero’ of The Lord of the Rings, and his relationship to the company of aristocrats on which he never ceases to wait (except when explicitly ordered not to at Aragorn’s wedding) is at the heart of Tolkien’s Catholic worldview. Tolkien believed in a hereditary Head of State and the divine right of Kings, and many of his tales are about the duties of royalty and the fealty of the common man. If you don’t understand that, I’d suggest you haven’t understood much of what his books are about.

One more thing. Bilbo and Frodo are both what today we would call — mistakenly, I think — ‘gay’, but in Tolkien’s day was more accurately called ‘queer’. It’s not called ‘The English Disease’ for nothing, and among young male students brought up in boys-only boarding schools then sent to sexually-segregated colleges and then war with little or no knowledge of women beside a few beefy matrons who washed their rugby shorts and the distant mothers who visited their boarding schools at Easter and Christmas, homosexuality was the default sexuality of their youth and early manhood. Again, Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited is the background to this peculiarly English context.

In ‘The Quest of Erebor’ from Unfinished Tales, Gandalf remarks of Bilbo that ‘he had never married. He was already growing a bit queer’. Of course, Tolkien used this word in its more general sense to mean strange or peculiar, but I would argue that he used it not only in that sense. Bilbo, Tolkien wrote on the first page of The Lord of the Rings, ‘had many devoted admirers among the hobbits of poor and unimportant families’. And like Oscar Wilde — with whose tragic fate Tolkien would have been familiar — it would be with them that Bilbo shared his flirtations. But he had no close friends, Tolkien adds, ‘until some of his younger cousins began to grow up’. Frodo, also being queer and in his ‘tweens’ (Tolkien’s neologism for the irresponsible 20s) was the obvious choice to come and live with him.

I can’t believe that many of the men of Tolkien’s age, class, education and experiences — and particularly his Oxford peers to whom he read his tales as they were written — wouldn’t have recognised this as a description of something with which they were quite familiar but never mentioned. This is, of course, that ‘love that dare not speak its name’, as Oscar Wilde said at his trial, between an older and a younger man. Bilbo and Frodo, both of whom remained bachelors, have that relationship. And when Bilbo leaves for Rivendell, Frodo looks for something similar with Sam. Sam isn’t ‘queer’, but as the two approach and pass into Mordor, both, at different times, express their love for each other. Somewhere in The Two Towers (‘Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit’) Sam, looking at the sleeping Frodo, says to himself: ‘I love him. He’s like that, and sometimes it shines through, somehow. But I love him, whether or no.’

Now, I’m not for a moment suggesting that Bilbo, Frodo or Sam were buggering each other in the fields behind Bag End — though at the same time I don’t want to deny them, even in the reader’s imagination, the sexual experience so many British men of that time were denied by the illegality of homosexuality under British law until 1967. I’m talking about where their affections lay and were directed, and this relationship between Frodo and Sam — which Sam renounces, reluctantly, when he marries Rosie Cotton and has a dozen or so kids, leaving the thrice-wounded Frodo to sail off into the sunset — is quite clearly a homosexual one. If their mutually declared love for each other is not a passionate but necessarily unconsummated homosexual relationship — necessarily, because Sam, like so many soldiers after him, has to return from war and marry his waiting sweetheart — I don’t know what is.

One only has to imagine Rosie’s reaction, however, when her newly-wed husband tells her that they’re not setting up home together — as she had every reason to expect — but instead are moving into Bag End with his former employer and the man he’s been looking after for over a year, to realise just how queer their relationship was. ‘I feel torn in two’, Sam tells Frodo at the end of the book (‘The Grey Havens’) when his master asks him when he’s going to move in with him. ‘I see’, said Frodo: ‘you want to get married, and yet you want to live with me in Bag End too?’ To which he offers the compromise of Sam and Rosie both moving in (Jackson’s film, aware of how queer this would appear to US audiences, relocated Sam and Rosie back in his previous home in Bagshot Row).

It’s still not unusual for the landed gentry to have married servants living in quarters within their homes; and despite his exploits in defeating Sauron, Sam continues — presumably with the help of his wife — to wait on his employer (‘there was not a hobbit in the Shire that was looked after with such care’). But Frodo’s departure for the Grey Havens was his way of letting Sam return to the heterosexual order their relationship threatened, his way of allowing Sam to have a (huge) family. Even after Frodo leaves, Sam, who names all seven sons after his male friends, starts, of course, with his beloved ‘Mr. Frodo’.

Ian McKellen, the gay English actor who played Gandalf in the Peter Jackson films, recognised this, and according to Sean Astin, the straight American actor who played Sam, told him that when he greets the awakening Frodo in Rivendell he must follow what the book says, which is that he ‘took his left hand, awkwardly and shyly. He stroked it gently, and then blushed and turned hastily away.’ Unfortunately, Jackson and his co-writers weren’t listening, and neither was Elijah Wood.

The most accurate depiction of this very English relationship I’ve seen is that by the English comedians Charlie Higson and Paul Whitehouse in the BBC series The Fast Show. They play, respectively, Lord Ralph Mayhew, an unmarried homosexual aristocrat who lives on his inherited country estate, and Ted, his married Irish gamekeeper. Like Sam at Bag End, the character of Ted worked on the estate when it was owned by Lord Mayhew’s father and was inherited along with it. Like Sam to Rosie Cotton, Ted is married. And like Sam at the Green Dragon Inn, Ted sticks up for his ‘master’ when the local lads, like Ted Sandyman, call him ‘queer’. If you want to see Frodo and Sam, have a look at it on YouTube.

Tolkien was a Roman Catholic in both observance and beliefs, and I’d guess he would have regarded sodomy as an ‘abomination’, as it says in Leviticus 20:13. But that doesn’t mean he didn’t recognise the existence and, I would also guess, the sanctity of love between men. With Frodo transformed by his sufferings into a Christ-like figure, Sam’s love becomes sublimated as that of a disciple to our Saviour. But as his letters to his children reveal, Tolkien had a profound understanding of emotional relationships, which bore fruit in the many love stories (such as Beren and Lúthien, but also Túrin and Beleg) that are written into a mythology dominated by conflict and war. Love between men was a part of his own experience as an orphan, a student and a soldier, and the relationship between Frodo and Sam — which breaks off from the rest of the Company from The Two Towers onwards to run in a parallel narrative through Books IV and VI, and whose parting at the Grey Havens is the book’s last word — is the intimate tale at the heart of the world-changing events that make up The Lord of the Rings.

The book ends with Sam returning to his former master’s home, where the evening meal is waiting and his wife places his first child — a girl, Elanor, not the boy they were waiting to call Frodo — on his lap. ‘Well, I’m back’, he says. And it’s from more than the Grey Havens.

* Notes to a Book on Tolkien

‘For we are attempting to conquer Sauron with the Ring. And we shall (it seems) succeed. But the penalty is, as you know, to breed new Saurons, and slowly turn Men and Elves into Orcs.’

— J. R. R. Tolkien, Letter to Christopher Tolkien (6 May, 1944)

Until I write this book, I include here, for those interested in all things Tolkienian, these extracts from online comments on his work written between August 2020 and November 2023.

1. In ‘An Unexpected Party’, the opening chapter of The Hobbit, Thorin refers to the Withered Heath, the land between the arms of the Grey Mountains, as where ‘the great dragons bred’. However, I’ve always understood that dragons were created by Morgoth, who sent evil spirits into bodies he had fashioned or bred for them out of existing beasts, just as Tolkien (somewhere) describes spirits of evil Maiar entering into the bodies of creatures (e.g. large and powerful orcs such as Azog, or the werewolves of Sauron on Tol-in-Gaurhoth) at different times throughout the ages. If that’s the case, Smaug must have been created in the First Age, and as a winged fire-drake around the time of Ancalagon the Black. To my ears, his reference, in conversation with Bilbo, to laying low ‘the warriors of old’ and the ‘first men’ reflects this. Like the Balrog freed in Moria by the deep-dwelling Dwarves, Smaug is an evil of an ancient time ‘awakened’ from slumber by the greed of the dwarves mining for gold in Erebor, the evil of the Ring, and ultimately the evil of wanting power — which must be expiated by the respective sacrifices of first Bilbo and then Frodo.

2. The biggest difference between book and film in the chapter titled ‘At the Sign of the Prancing Pony’ is the character of Aragorn. This is when we first meet him in The Lord of the Rings, and yet the film has chosen to change almost everything about what Tolkien tells us about him: the way he looks, talks, what he wears and carries, and above all his character. Aragorn is always described as tall, at least 6’4” by Númenórean measure (in the notes collected in The Nature of Middle Earth, Tolkien says he was at least 6’6” and very strong), while Mortensen is 5’11” at best, with a slight build, and very little physical presence. Aragorn, as a Númenórean with Elvish blood, is beardless, while Mortensen has the permanent designer beard that was popular when the films were made. Aragorn initially speaks with a Bree accent, but quickly drops it when talking to Frodo, and his voice is later described (on Weathertop) as ‘rich’. Mortensen, for some reason, speaks with a US-imitation of an Irish accent (‘Let the Lord of the Black Land come forth’, to be sure, to be sure). Aragorn carries the shards of Narsil in his scabbard, while Mortensen has an unidentified sword until Elrond magically turns up in Rohan with the reforged Andúril. Above all, Aragorn faces a quest of Beren-like levels of impossibility: he can only marry Arwen if he defeats Sauron; while Mortensen, for reasons I can’t begin to imagine, has renounced both his lineage (‘I do not want that power. I have never wanted it!’) and with it his one chance of marrying Arwen, which is a complete betrayal of his character. More generally, Mortensen behaves like an American tough guy (for example, throwing Frodo to the ground like the inn bouncer or punching his way into Meduseld), while Aragorn is the noblest man in the whole of Middle Earth, brought up by the High Elves of Rivendell, with the blood of a Maiar (Melian) in his veins. Viggo Mortensen seems like a nice person, and he’s a linguist who speaks six languages — which is unheard of among America’s monolingual actors — but he’s not Aragorn.

Who would I have chosen for the role? My ideal actor would have been Timothy Dalton, who had the dark looks (he’s famous for playing Heathcliff and Rochester), something like the height (6’2” to Aragorn’s 6’6”), and, most importantly, the rich, classically-trained English voice and the physical poise and stature to play Aragorn. Or, if Dalton was too old for the physical requirements of the part (he was 54 when principal photography was conducted in 1999), then Mads Mikkelsen, the Danish actor, who has the looks, build (6’ and a former gymnast) and slightly distant air of Aragorn. And I’d have cast Liam Neeson as Boromir. Sean Bean excels in bringing warmth to these roles, just as he did playing Eddard Stark, but he’s nothing like Boromir physically. Bean is 5’10” and has a slim build; Boromir is 6’4” and heavily built, the physically strongest of the Company. Neeson (also 6’4”) matches Boromir in stature and build, has dark hair (not blond), and could have a crack at the formal speech of Gondor, as opposed to Bean’s Northern accent, which was better fitted to the Rohirrim. Neeson was 47 years old when filming began, which is 7 years older than Boromir, but he looked fighting fit, as he showed in the execreble The Phantom Menace that year.

3. There is no mention by Tolkien of beards on the carved figures of Isildur and Anorien at the Argonath, just as there isn’t in the description of Aragorn’s ‘shaggy head of dark hair flecked with grey’ when the hobbits meet him in Bree. That, surely, would be the time to mention his beard if he had one. If someone isn’t described as having a beard, it’s safe to assume they don’t have one. Aragorn doesn’t have a beard. As for the statue of the king at the crossroads, the Gondorian kings, as Gandalf says with some aristocratic distaste, became mixed with that of ‘lesser men’. But the question of whether Númenóreans, even when their blood was mixed with Middle Men, could grow beards is neither here nor there. Throughout history, different tribes, cultures, civilisations have had different ways of dressing their hair. The Romans, famously, didn’t grow facial hair for much of their empire, not because they couldn’t but because they chose to be clean-shaven, presumably to distinguish themselves from the bearded ‘barbarians’ to the north. Similarly, whether they could grow a beard or not, I’d guess Númenóreans distinguished themselves from the Middle and Wild Men of Middle Earth by shaving their chins, presumably, also, because it drew them closer to the Elves, who couldn’t grow beards (except, as with Cirdan, when they entered the third part of their age), and the immortality they craved.

I understand that in the films men are distinguished from Elves by making the former have beards, but that’s because the Americanisation of the races and characters in the films (with a skateboarding Legolas and dwarf-tossing Aragorn) meant they weren’t able to convey the difference between them except in making Elves into supermen (Legolas), or effete (Haldir), or speaking with bizarrely deep voices (Elrond and Galadriel). Like so much about the films, that’s a result of their failure to convey the cultures of the different races.

4. Aragorn is the tallest of the Company of the Ring. Tolkien states so clearly in the ascent of Caradhras. But in the film Legolas is shown as the tallest, as he is also turned into a sort of Marvel-comics superhero, single-handedly killing an oliphaunt. Aragorn, in contrast, who in Gandalf’s words is the hardiest man in Middle-Earth, is almost killed by a band of orcs in a skirmish before Helms Deep, which is about as stupid as the film gets as Jackson padded out The Two Towers to end in the over-extended (40 minutes) battle scene, and another betrayal of his character and his stature in Middle Earth. But when I speak of the contrary stature of Viggo Mortensen, I also mean his film presence. From what I’ve read about him he’s a nice and intelligent man, but he holds himself like a Californian surfer (his sweaty dash across the muddy courtyard of Meduseld being an example), not the heir of Elendil.

5. Throughout the three films of The Lord of the Rings, just about every main character gives up or has doubts or otherwise departs from their character in the books: this includes Pippin and Treebeard, Faramir, Legolas, Elrond, Sam (!) and Aragorn. This, again, is a result of the filmmakers’ inability to convey anything other than the standard stereotype of Hollywood narrative film, which is the reluctant hero who overcomes his personal doubts to become ‘awesome’ (as the Americans say). But Tolkien, who fought in the Great War and belonged to a very different generation and country, understood the kind of fortitude in the face of almost certain defeat he dramatised in The Lord of the Rings. It is because of the impossibility of Aragorn defeating Sauron and thereby gaining his Kingdom and his Queen that his stoic determination to try is so heroic. I think Tolkien would have been horrified by what Peter Jackson and Viggo Mortensen did to his King. It’s one of the reasons why, despite their many qualities in visualising Middle Earth, it’s such a shame that generations of kids will grow up with this comic-book depiction of the majesty of Tolkien’s characters before they have a chance to read his books.

6. Whatever you may think of Peter Jackson’s films, if you don’t understand why Tolkien would have been horrified at what they have done to his secondary world — and which was expressed by his son and literary executor, Christopher Tolkien (‘They eviscerated the book by making it an action movie for young people aged 15 to 25’) — I don’t think you understand that world and the values on which it was built and professed. Jackson’s films follow the standard narrative and motivations of every Hollywood film made in the past forty years, with its reluctant heroes, sacharine sentimentality and choreograped violence, with every encounter turned into an half-hour fight scene. In contrast, Tolkien’s secondary world is the antithesis of everything US culture has imposed upon the primary world since The Lord of the Rings was published in 1954-55. The fact people today don’t see this — and even cite the faithfulness of Jackson’s films against the travesties of The Rings of Power series — is evidence of how totally that culture has colonised not only our art but also our minds. Both films and television series are an image of what would have happened in the story if — as Tolkien speculated in a letter to Mrs. Eileen Elgar in September 1963 — Gandalf had taken the Ring, which is what has happened in the real world: a ‘self-righteous’ (Tolkien’s words), totalitarian world that conceals its addiction to the spectacle of violence under trite sentimentality while broking no dissent, no alternative vision, no challenge to the rule of Mordor.

7. I’ve always thought it very odd that the Second Age doesn’t end with the downfall of Númenor — which not only meant the drowning of the island but also the removal of the Undying Lands from the circle of the world (effectively transforming the world from a Medieval flat-earth to a Modern globe) — but rather with the temporary defeat of Sauron. The Second Age begins with the rising of Númenor from the sea, and so it seems right that it ended with its drowning. Sauron’s a key figure in the fate of Arda, but the changing of Arda, even more than it was by the Valar at the end of the First Age when Beleriand sunk beneath the Sundering Seas, surely trumps that. For me, the Third Age began with the Last Alliance and the cutting of the Ring from Sauron’s hand, and ended with the destruction of the Ring. It’s the Age of the heirs of Elendil arriving in Middle Earth up to Aragorn’s unification of their divided kingdoms. But Tolkien didn’t agree. Why?

8. Eärendil is not pronounced ‘Yarendle’. Eä is not a dipthong but two syllables, pronounced (roughly) ‘Ay-ah’. And the final syllable ‘dil’ is not uvular (as in modern English ‘handle’) but accentuated as in ‘diligent’, with the final ‘l’ pronounced. And, as Tolkien always emphasised, the ‘r’ is rolled (with the Elves looking down their aristocratic noses at those who spoke with the untrilled ‘r’). So: Eärendil is ‘Ay-ah, rrren-dill’ I know this is a bit difficult for American speakers of English, but this name, which Tolkien found in the Crist of Cynewulf, a poem in Anglo-Saxon, was the inspiration for what might be called the genesis of Tolkien’s mythology, his 1914 poem ‘The Voyage of Earendel the Evening Star’, and deserves to be pronounced as Tolkien intended. I’d also suggest, based on the recordings Tolkien made of his readings, that both ‘Gondolin’ and ‘Glorfindel’ have the emphasis on the second syllable: ‘Gon-DO-lin’, not ‘GARN-d’-lun’, and ‘Glor-FEEN-dell’ not ‘GLOR-fin-dle’.

9. On the pronunciation of the name of Celebrian, daughter of Galdriel and Celeborn, wife of Elrond, mother of Arwen, we should recall that Tolkien’s fascination with languages could be dated to him seeing, while playing in the Worcestershire countryside of his childhood, delivery vans travelling between Birmingham and Cymru (which the unlearned, base and rustic call ‘Wales’), and seeing on their sides the Brythonic language of that nation, and wondering what it meant and how it was structured. Not only for this reason, Sindarin resembles Cymraeg (Welsh) in its generally uninflected grammar, and in its emphasis, which in general falls on the penultimate syllable of the word. Celebrian, therefore, has the stress on ‘bri’, not ‘leb’. Also, like Cymraeg, Sindarin ‘i’ is pronounced ‘ee’. Thus, Celebrian would be pronounced ‘Kel-e-BREE-an’. Celeb, after all, is a common element in Sindarin names, as in Celeborn, Galadriel’s husband. But Celebrian is a very Welsh-sounding name anyway when pronounced this way.

10. When Frodo asks Galadriel why he can’t see the minds of the other ring-bearers — as she says she can see that of Sauron and, she suggests, Frodo’s own mind — she responds that Frodo hasn’t trained his will to the domination of others (and that he isn’t of sufficient spiritual stature). But she adds that, since Frodo knew what the Ring is, only thrice has he put it on his finger (in the house of Tom Bombadil, in Bree and on Weathertop). This suggests that, as the bearer of Nenya, she was aware when Frodo used the Ring. So why, given that not only she, but more particularly Gandalf, bore a Ring of Power, did Gandalf, who was often in proximity to the One Ring, not recognise it for what it is, or at least as one of the Greater Rings, as soon as Bilbo found it?

The obvious answer is that The Lord of the Rings wouldn’t have been written; but it does seem hard to sustain that Gandalf, Elrond and Galadriel didn’t feel ‘a disturbance in the Force’, as Darth Vadar might have said, as soon as Bilbo and Frodo put on the One Ring. There’s a suggestion, perhaps added in the revised version of the Hobbit, when Bilbo tells his first ‘lie’ about the Ring to the Dwarves after escaping Goblin Gate, and Gandalf gives him a ‘queer look’ from under his bushy brows. I seem to remember Gandalf saying, I think in ‘The Council of Elrond’, that only the Greater Rings (the twenty?) conferred invisibility, so he must have known, as himself the bearer of Narya, that Bilbo had something more than a ‘magic ring’.

Tolkien also says that the Nine were ‘held by Sauron’. Which means the Ringwraiths didn’t wear the Nine, not even the Witchking. So although the rings reduced already powerful mortal men, Númenórean Lords and Eastern Kings, to wraiths, it wasn’t the source of their power. So what was that source? Did it come from Sauron’s control over them? Were they the embodiment of his will, the fingers of his hand as it stretched out for more power?

11. The chapter on ‘The History of Galadriel and Celeborn’ in Unfinished Tales is perhaps the least satisfying, partly because of the lack of continuity, partly because of the constantly changing conception Tolkien had of the Lady Galadriel. I would guess that, as he neared the end of his life, and perhaps more immediately his wife neared hers, like any Catholic his idolisation of the Virgin Mary reached its apotheosis; but I prefer the Galadriel of pride and doubt who followed Fëanor to Middle Earth seeking vengeance and refused the pardon of the Valar after the overthrow of Morgoth, to the guiltless leave-taker from the Undying Lands of Tolkien’s last writings.

12. I reread The Lord of the Rings recently, and was once again struck by the incongruity of the status of Elladan and Elrohir. Throughout the books, Aragorn in particular reveres the memory of Elendil and Isildur. These were Kings of Arnor and (with Anorien) Gondor, and although they were not descended in direct line from the Kings of Númenor, they could claim that this was only because of the patriarchal line of descent, and that in fact it was their matriarchal line, and not that which led Númenor to its ultimate downfall, that represented the true line of Elros. And, of course, Númenor was the great power of the Second Age, though it fell fairly quickly into despotism, extracting taxes and tolls from the peoples of Middle Earth rather than sharing knowledge and wisdom.

Elladan and Elrohir, however, as the sons of Elrond, are the nephews of Elros, the first King of Númenor. And although, after the death of Gil-galad, Elrond refused the kingship of the Noldor, which was by right his, and remained the mere Lord of Imladris, Elladan and Elrohir are both crown-princes of the royal line of the Kings of the Noldor. And, of course, they’re both 2,889 years old during the War of the Ring, and bear within them, in a far purer mix than, say, Aragorn, the blood of a Maiar — Melian, the mother of Lúthien Tinúviel. In fact, in my misspent youth I once worked out that that they are 6/48ths Noldor, 8/48ths Vanyar, 7/48ths Teleri, 16/48ths Sindar, 10/48ths Edain, and 1/48th Maiar. In other words, they’re about as ‘royal’ as you can get in Middle Earth in the Third Age, and we know how important royalty was to Tolkien as a measure of stature.

And yet, in the books they’re referred to as little more than mentors to the young Aragorn, as messengers from their father, as fellow riders with the Grey Company, and are invariably referred to merely as ‘The Sons of Elrond’. I know that the future of Middle Earth depends on the victory of Aragorn and the Fourth Age he will rule, and that the time of the Elves is over. But I find it very odd what a low profile Elladan and Elrohir are given compared to, say, the reverence with which Arwen is depicted. After Galadriel, Elrond and Glorfindel, they’re the highest of the High Elves left in Middle Earth. On the other hand, I kind of like it, in the same way that my favourite Elf from the entire legendarium is Beleg Cuthalion, a mere march-warden of Thingol (though an ‘awakened’ Elf who ‘wist no sire’).

13. I’ve always been fascinated by the story of the first Elves who were ‘awoken’ in Cuiviénen rather than born, and thought Tolkien’s comment about the counting game for children meant that Imin, Tata and Enel were, in fact, Ingwe, Finwe and Elwe. If you were going to choose ambassadors to visit the Valar, wouldn’t it be your leaders? But the just-published book, The Nature of Middle-Earth, has an extraordinary text, dated 1959 (so written after The Lord of the Rings), which clarifies that Ingwe, Finwe and Elwe were direct descendants of Imin, Tata and Enel, and, according to Tolkien’s (changing) chronology, 5th or 24th and 25th generation Elves. Tolkien went through three different chronological schemes, but Imin, Tata and Enel refused to visit Aman, and saw the selection of Ingwe, Finwe and Elwe as ambassadors, and their glowing account of the Undying Lands when they returned, as a youthful rebellion against their authority and threat to the unity of the Elves. So the three original leaders of the Elves ended up being Avari, Dark Elves, and never saw the light of Aman.

14. Tolkien wrote that three of the Ringwraiths were Númenórean lords, and one of them an Easterling king. I always felt that the Witch-King was one of the former, a Númenórean lord who, from c. 1800 of the Second Age, when the shadow first fell on Númenor, began to establish dominions on the coast of Middle Earth. It was at this time, according to ‘The Tale of Years’, that Sauron extended his power eastwards after his defeat by Tar-Minastir 100 years earlier. Looking to extend his own power, this Númenórean lord — probably a relative of the King and with the longer life of the descendants of Tar-Elros, but not in the line of succession and therefore, by that time in the spiritual decline of Númenor, bearing a grudge — began to move into the East, first with trade, then by war and conquest. And it was there that Sauron ensnared him with a Ring.

That leaves 450 years for an already mature Númenórean — say 200 years old, about the age he would have taken the Sceptre of Númenor were he in line to the kingship — to fade into a wraith. In that time, I imagine him becoming a ruler of some Eastern kingdom, aided by Sauron and his Ring. I know it’s Khamul who is called the ‘Shadow of the East’; but ‘The Tale of Years’ makes no mention of Sauron returning from the East until he is taken prisoner by Ar-Pharazon in 3262. And in the ‘Akallabêth’ it says that Sauron only began to assail the Númenórean strongholds on the sea after the Ringwraiths arose, so post 2251. So my guess is that the kings, sorcerers and warriors who became the Ringwraiths were seduced while Sauron was extending his power into the East.

I’ve also always felt that the Witch-King’s power, which appears to be not only through the fear that all the Nazgûl wield but in spells (for example, his holding spell at the ford of Bruinen that breaks Frodo’s sword; or his spell of opening at the gates of Minas Tirith, where he ‘cried aloud in a dreadful voice, speaking in some forgotten tongue words of power and terror to rend both heart and stone’), was a result of him being a sorcerer rather than, or as well as, a king. None of the other Nazgûl are shown wielding this kind of power. He was, after all, the Witch-King of Angmar, and not necessarily of any kingdom when he was still a man and not yet a wraith. So my theory is that he’s a Númenórean lord who turned to witchcraft and sorcery under Sauron’s tutelage during the latter’s 450 years withdrawal and consolidation in the East between 1800 and 2250.

15. Barrows are a theological problem for Tolkien, who as a Catholic would have to confront the salvation of humans who lived and died (and built their burials) before Christ. From their description in ‘Fog on the Barrow Downs’ they were round barrows, which are predominantly from the Bronze Age, rather than the older long barrows, which were built in the early Neolithic. The barrows in Warwickshire, which Tolkien would probably have known, are from the Bronze Age. When the Númenóreans returned to Middle Earth and found the burial mounds of the Men of the First Age, they had to ask: what happened to them when they died, when they had never been visited by the Angelic Order of the Valar, or heard of Illuvatar/Eru? Can a soul that has never heard of God leave the world?

Their reaction was more enlightened than the Christian Church, which in England, at least, generally denounced this and other evidence of pre-Christian religious beliefs as pagan devil-worship (etc). The Númenóreans, in contrast, recognised their kinship with the First Men, honoured their burial sites if not whatever religious beliefs they had, and even, it seems, buried their own dead in similar barrows. That still seems to me odd, though. These were ‘pagan’ rites, made in the absence of the knowledge of Eru, while the Númenóreans were strict monotheists. They buried their dead, rather than burned them; but to use the barrow form of burial sounds close to heresy. Yet the mound to which the Hobbits were taken by the wight was undoubtedly the grave of a Númenórean warrior, as it was his dagger that pierced the Witch-king’s ‘mighty knee’. But I’ve never quite understood what he was doing in a barrow.

For those from a country without barrows, they aren’t dug into a hill, like hobbit holes. In Wales, where they’re called Cromlechs, and in France, where they’re called dolmens, they are built from three upright rocks surmounted by an immense capstone, the whole lot covered in smaller stones and turf. In England, they’re usually built of corbelled stones, again around huge stones set at the entrance, over which a mound of earth was raised, forming their distinctive shapes, usually on the horizon. In 2020 I visited the West Kennet Long Barrow in Wiltshire, which is close to but far older than the Avebury Henge. It’s huge, dates to c. 3,700 BC, and has numerous chambers left and right as you go in. Lots of room for the First Men, a Númenórean warrior and even a Barrow Wight. Interestingly, it was used as a burial chamber for about 450 years, which might have inspired Tolkien to think of the Númenóreans using the barrows on the Barrow Downs to bury their own dead.

In the light of which, I always cringe when Peter Jackson depicts Aragorn tossing the Hobbits their magically-appearing swords on Weathertop, as if they were so much cutlery for a camp meal he’d been keeping under his cloak. Denethor’s reaction, when Pippin presents the hilts of his sword to him in Minas Tirith, is more respectful: ‘Many, many years lie on it. Surely this is a blade wrought by our own kindred in the North in the deep past?’ Even the Mouth of Sauron, when he shows Sam’s blade to Aragorn and Gandalf, refers to it as a ‘blade of the downfallen West’. Hailing from a younger country, perhaps Jackson doesn’t appreciate the aura such ancient artefacts have. It would be like me tossing a blade recovered from the West Kennet Barrow to a bunch of teenagers today.

16. What did Gandalf mean when he tells Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli on their meeting in Fangorn that the creatures that delved and crawl in the tunnels beneath Khazad-Dum are ‘older’ than Sauron? As a Maiar, and therefore a lesser spirit of the angelic order of the Valar, Sauron existed before Ea (the universe), and the only being older than than they is Eru/Illuvatar (God). I’d guess what he means, therefore, is the more precise philosophical meaning of the word ‘existed’, from the Latin exsistere, meaning ‘come into being’. This suggests that the Watcher in the Water at the west door of Moria came into Arda (the earth), and is perhaps coexistent with it, before the Maiar clothed themselves in the flesh of the world and entered Arda.

Apropos which, I have an observation on who awakened the Watcher in the Water to the presence of the Company of the Ring. Since Jackson turned Frodo into the equivalent of a wealthy American teenager with his best buddy Sam, it would seem odd to make him berate Boromir in the film, as he does in the book, for throwing a stone into the quiet pool. So instead the stone throwing is performed by the incessantly annoying Pippin. But in the book Frodo is 50 years old, with the suggestion he’s the wisest Hobbit in the Shire after Bilbo left for Rivendell; while Boromir is a noticeably rash and unwise 41-year old man. However, it wasn’t his stone that awoke the Watcher. As Tolkien takes care to clarify, ripples formed on the surface of the lake beyond where the stone landed, and simultaneously with its entry, not afterwards. So who, or what, awoke the Watcher?

While circumnavigating the lake, the company come across a narrow creek at the north-west corner. ‘It was green and stagnant, thrust out like a slimy arm towards the enclosing hills.’ Led by Gimli, all the Company crossed, finding it no more the ankle deep. Frodo, nevertheless, ‘shuddered with disgust at the touch of the dark unclean water on his feet’. It was this moment to which Frodo referred when he told Gandalf later that he ‘felt something horrible was near from the moment that my foot first touched the water’. So the Company all helped wake up the Watcher in the Water when they tramped through the creek; but then a company of wargs might have done the same. I’d guess, however, that it was Frodo, as the Ring-bearer, that alerted it to the presence of evil. Gandalf had warned Frodo that Sauron’s Ring draws evil creatures to it, even evil creatures that are ‘older than Sauron’.

17. The Lady Haleth, who after her father and brother were slain by orcs became Chieftain of the Haladin — the second and least impressive House of the Edain to enter Beleriand — was an echo of Queen Boudica. A taste for matriarchy survives still in the imagination of we Britons, from Queen Elizabeth I to our former monarch and the Iron Lady herself (the monstrous Thatcher), which is antithetical to the more macho American mind, as we saw with the failure of the equally monstrous Hilary Clinton to beat the hyper-macho Donald Trump. Another female character, and Tolkien’s censorial response to feminism, is Erendis, the wife of Aldarion, King of Númenor. Queen Beruthiel, also, is another feminist. As, of course, is Éowyn, whose ‘taming’ through marriage to Faramir is one of the less convincing of Tolkien’s love stories. Tolkien wasn’t as uninterested in women as the pre-pubescent woke-critics of today affirm. His letters to his sons are a mine of wisdom on the relations between the sexes, albeit always from the position that we live in a ‘fallen world’ (which is Catholics’ explanation for why relations between the sexes are so difficult).

18. Tolkien, however, was overly harsh about Queen Beruthiel, whom Aragorn mentions when the company are seeking a way through the mines of Moria. She was, as so many queens have been before and after her, forced into marriage with a man she clearly didn’t love or even like, snatched from her home and her people, and expected to bear his children and future kings. As a child of the southern deserts, she hated and perhaps feared the sea, so ran away to Osgiliath. There she was surrounded by the competing lords of an alien people, who disliked her as a foreigner, feared her as a woman, and were interested in her not having a child and, thereby, of advancing their own claim to the throne. Maybe they poisoned her to make her infertile. Maybe the king couldn’t get aroused when confronted with a woman who didn’t submit to him. Maybe they just never made it in bed. Unsurprisingly, she found friendship in the animal kingdom among cats, the friends of housebound women. A virtual prisoner in her own home, she used these to uncover plots against her by the Gondorian lords, and even by the King.

Eventually, the King had enough. The other lords were conspiring against him. They demanded an heir to the throne. So he did what every other king in history has done. He blamed the queen, and sentenced her to a distant death by sea, not having the courage himself to sign the execution papers less it stain his reputation. Then his propaganda minister started the story about tortured cats and witch-like powers. Her real name was erased from the records, and she went down in history as merely ‘Beruthiel’, which in Sindarin means ‘angry queen’, a classic example of passive aggressiveness that lasted for over 2,000 years, until it was repeated by Aragorn. Far from being ‘the most evil woman’ in the Third Age, I’d say she is a feminist heroine who refused to be a submissive brood-mare for her King and paid the price. Whatever her real name was, she deserves more respect than the patriarchal Aragorn — and Tolkien — gave her.

19. If Fëanor were a character in a role-playing game, what would his moral alignment be? He drew a sword on his brother in the Blessed Realm; named Illuvatar as witness and the Everlasting Darkness down on him and his children on a vow to possess works of his own hand; defied the commands of the Valar; slew his own kind for their ships; abandoned his half brother and his people to suffering and death on the Helcaraxe; and then, before dying, committed his seven sons and their people, and with them pretty much the whole of Beleriand, to fulfilling a vow he knew was impossible. Fëanor gets far too easy a ride, I think, like a lot of the Noldorian and Sindarian leaders of the First Age. Fëanor is chaotic-evil.

Elrond, Celeborn and Galadriel look down their aristocratic noses at Men from the vantage point of their own decline in the Third Age, but Elves were often as evil, or at least as greedy for wealth and power, in the First Age, particularly the sons of Fëanor, who commit the most atrocious crimes. Like his fellow middle-class Catholic, Evelyn Waugh, Tolkien was, I think, blinded to the evils on which aristocratic privilege is founded. There are more than a few similarities between the beautiful but doomed Sebastian Flyte (of Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited) and the High Elves of the West, who retire from the conflicts of the world into private intoxication. Like Waugh, Tolkien wrote at a time when the aristocracy of Europe seemed to have fallen after the Great War, when in reality they were just being reborn as the industrialists, arms dealers and oligarchs of Mordor.

20. I re-read The Silmarillion and Unfinished Tales recently, and as always groaned at the military incompetence of the Noldor. Even in the successful Dagor Aglareb (the third of the Battles of Beleriand) their forces were split by the hundreds of miles of the plain of Ard-Galen. As the crowned heads of Europe took 20 years to learn under their repeated defeats by Napoleon Bonaparte, unless your forces are able to mutually support each other within a days march it’s not a ‘pincer movement’ you’re enacting, it’s your divided forces that are being defeated in turn. For the relatively small size of the forces (Tolkien is vague, but the army of Gondolin, for instance, is only 10,000-men strong), Ard-Galen is far too wide for Maedhros in the east and Fingolfin in the West to support each other, as Morgoth demonstrated when, in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears (the fifth Battle of Beleriand), he divided and defeated them in turn.

This raises a question about Tolkien’s military knowledge. He trained as a lieutenant before the Great War and saw first-hand some of the Battle of the Somme, which presumably informed his image of the pits and trenches through which Morgoth releases his forces in the Battle of Sudden Flame (the fourth Battle of Beleriand). But otherwise his depictions of, for example, the siege of Angband, or the fall of Gondolin, or the defeat of Menegroth, or of any of the battles he describes right up to the Field of Pelennor, is military fiction. Fortresses like Minas Tirith were built to resist forces twenty times the strength of their garrison for months on end, not to be defeated in a day and a night. I know narrative pacing takes precedence over reality, but how is it that a former soldier knew so little of warfare? Is it because he knew so much about narrative?

21. The Eldar appear to be trapped in a military ethic of the individual Hero, somewhat equivalent to the heroic figures of Greek mythology or, for Tolkien, the pagan warriors of Nordic mythology; while Morgoth operates within a Medieval model of warfare. I imagine Tolkien, who hated the machine, viewed siege weapons as the precursors to the mechanised warfare of the Great War in which he fought and lost so many friends and countrymen. But it’s a little hard to reconcile this with the Naugrim (dwarves) who revelled in machines, and as miners would have been among the first to develop the technologies and techniques of medieval siege warfare, including how to undermine the walls and towers of Thangorodrim.

The ill discipline of Fingon’s forces in the Battle of Unnumbered Tears was inexcusable, and comparable to the charge of the Heavy Brigade (Scots, Blues and Royal Dragoons) at the Battle of Waterloo, which, for all its initial success, deprived the Duke of Wellington of his entire heavy cavalry contingent for the rest of the day. Famous in Tolkien’s time, perhaps it was this heroic but disastrous incident that he had in mind when describing the Eldar’s abandonment of the defensive high ground at the foot of the Ered Wethrin to go careering down into the plain and Morgoth’s waiting trap.

The betrayal of Ulfang and his Easterlings also has a parallel in the Napoleonic Wars, when the Saxon division on the French side at the Battle of Leipzig (1813) turned on their former allies, to decisive effect. They too had a motivation, with Saxony having been formed by Napoleon as part of the Confederation of the Rhine, under which they were forced to provide a military contingent to the Grande Armée. After the disaster of the Russian campaign and the impossible position Napoleon adopted at the battle of Leipzig (with his back to the River Elster), they were right, politically and militarily if not morally, to go over to the Allies.

I imagine Ulfang did the same thing when he saw Maegroth’s armies being defeated. All the subsequent talk about them being agents of Morgoth was no doubt Elvish propaganda to cover the fact that, with their armies separated by the hundreds of miles of the Anfauglith (formerly Ard-Galen), Maedhros and Fingon were never able to support each other; and it was their outdated tactics and poor discipline that cost them the battle, not the betrayal of the Wild Men. But then, Elves, being a society of military aristocrats in a system of hereditary kingship, always blamed those they considered beneath them for their mistakes: Orcs, Men and Dwarves. Tolkien emphasised that the noontide of the Eldar was in the Undying Lands; and for all their inbred superiority, they were never made for the harsh realities of mortal lands.

22. Jackson’s Hollywood films aren’t part of the canon, and his insertion of Aragorn’s joke about dwarf women having beards has no bearing on Tolkien’s vision. In the recently published The Nature of Middle Earth, a text from 1972-73 titled ‘Beards’ has a footnote in which Tolkien states that neither Hobbits nor the Eldar had beards, but that ‘all male Dwarves had them’. I can’t see why Tolkien, a linguist, would add and itallicise the word ‘male’ unless it meant that female Dwarves were not bearded. And to clear up the question once and for all, he adds that Aragorn, Boromir, Faramir, Denethor, Isildur and all other Numenorean chieftains didn’t have beards (a result of their elven ancestry). Another thing Jackson got wrong.

23. If The Rings of Power television series is going to be set in the Second Age, then it could have addressed Western Imperialism, which is the model for the Númenóreans. They are in origin Northern Europeans, and are granted knowledge withheld from the Middle Men and Wild Men of Middle Earth. You could say they’re like the Roman Empire, but also the British Empire, and even the US Empire of today. They come to Middle earth first to teach and to trade, and the Wild Men benefit from the exchange. Over the centuries they establish permanent settlements and extend their influence into the South and the East. But eventually, like all empires, trade turns to military domination and the exacting of tribute at the point of a sword, and this leads them, eventually, to renouncing Illuvatar and worshipping Sauron. So race is not reductively equated to morality in Middle Earth, which would make Tolkien’s stories as boring as those who haven’t read them say they are.

The innate evil of Orcs, however, is a problem that Tolkien, who believed in the grace of God, struggled with. But Orcs aren’t a different race of humans, they’re a different species. Tolkien changed his mind on this, but orcs are elves that have been mutated by Morgoth. They are not Black or Asian humans, as woke is quick to assume. It’s true that orcs are described with some Orientalist stereotypes that were part of the Western imagination of Tolkien’s time, but that doesn’t make him or his books racist. Anyone who knows about his life and has read his letters knows that he was overtly anti-racist. When representatives of the Third Reich asked his permission to translate The Hobbit, Tolkien not only refused but denounced their assimilation of the Germanic myths to the ideology of National Socialism — which is more than the compliant acolytes of woke have done these past few years to the ideology of their corporate masters.

What Tolkien was, however — and in spades when concluding the first draft of The Lord of the Rings during the Second World War — was highly critical and even furious at the path Western civilisation was taking. If Amazon wanted to explore that through the Second Age they could have done so. They haven’t, I’d suggest, not just because they want to make a piece of corporate crap for woke kids, but because it would too obviously parallel the history of the West, and too obviously make clear what has been the truth for some time now: that, like the Númenóreans, we are now tyrants, military empire-builders and utterly corrupted by Sauron. So instead they use identity politics, which has been promoted as the official ideology of corporate capitalism precisely to hide this fact.

The most explicit commentary on race and morality in Tolkien’s books is probably the scene when Frodo and Sam meet Faramir, whose forces ambush a division of Haradhrim marching to join Mordor. We see the battle through Sam’s eyes:

‘Then suddenly straight over the rim of their sheltering bank, a man fell, crashing through the slender trees, nearly on top of them. He came to rest in the fern a few feet away, face downward, green arrow-feathers sticking from his neck below a golden collar. His scarlet robes were tatterered, his corslet of overlapping brazen plates was rent and hewn, his black plaits of hair braided with gold were drenched with blood. His brown hand still clutched the hilt of a broken sword. It was Sam’s first view of a battle of Men against men, and he did not like it much. He was glad he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man’s name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil at heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace.’

There’s real empathy and sympathy in that description of the dead man’s ‘brown hand’. We could do with more of the Professor’s understanding and wisdom about the lies that drive men to war, and less of woke’s readiness to denounce as racist anyone with a different vision of the world to them.

24. Those who think Tolkien uncritically equates race with morality (good elves and bad orcs) either haven’t read his works or are too blinded by their reductive ideology to understand what he’s written. In terms of the consequences of his actions (the Doom of Mandos), Fëanor is one of the most destructive and ‘evil’ of the characters in the First Age, yet the cause of that destruction and the thousands of deaths is not his race but his hubris, pride, lack of empathy, arrogance, greed, and above all his seduction by the materiality of power. No wonder Morgoth wanted to lure him to his side: he would have made a lieutenant second only to Sauron, perhaps. Indeed, I imagine Sauron started very much like Fëanor.

The identity politics of woke ideology reproduces the reductive understanding of good and evil because it serves the states and corporations funding its ideology, which depends for its cultural hegemony, as we’ve seen over the last two years of lockdown, on an enemy to fear or hate. What no-one seems to have asked yet is why Amazon, one of the most powerful and certainly the wealthiest corporation in the world, is intent on turning Tolkien’s work into a platform for disseminating woke ideology. We are living today in the equivalent of the Second Age, the Dark Years as they were called, when Sauron ruled most of Middle Earth and the minds of men, elves and orcs were poisoned by his lies and deceptions. We all know his lieutenants now — Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Larry Fink, Klaus Schwab, Benjamin Netanyahu, Ursula von der Leyen, Tedros Ghebreyesus, Agustín Carstens, Albert Bourla — and their fortresses of evil — the United Nations, the World Economic Forum, the World Health Organization, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the International Monentary Fund, the European Commission, the European Central Bank, the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization and the G20 nations. The question is, can those of us still fighting defend Lindon and Imladris against their invading armies, and will Númenor come to our aid before darkness covers the world?

25. Tolkien several times said that all stories are about one thing: death. The text titled ‘Athrabeth Finrod Ah Andreth (The Debate of Finrod and Andreth)’ from Morgoth’s Ring (volume 10 of The History of Middle Earth) is one of the most fascinating of his texts on death, and his most detailed exploration of perhaps his primary invention, which is not hobbits but elves, and the condition of not immortality but long life in the material world. It goes to the heart of his faith as a Catholic that Men, which in his conception are humans who have seen the light of God, have an existence beyond the confines of the world. To the woke ideologues who sniff at Tolkien’s perceived lack of depth and subtlety, this text is a sharp corrective. When I first read it, I thought it had echoes of Heidegger, who was Tolkien’s contemporary, and other twentieth-century philosophers of death, of which there are many.

But the text also says something about Tolkien’s view of the relationship between the sexes. All the other unions of humans and elves that we know of are between male humans and female elves. This not only accords with Tolkien’s love for his wife, Edith, who in her youth had raven hair and clear elvish eyes — a real model for Luthien in the young man’s newly sexualised imagination — but of his view that when a woman marries a man she makes a sacrifice of her personal ambitions in order to become the mother of his children. Tolkien wrote about this in his letter to his son, Michael (6-8 March, 1941), prior to the latter’s marriage. Undoubtedly, in such marriages between Elves and Men, it is the Elf that makes the sacrifice, giving up millenia of life for her lover. It is always the female partner, therefore, Luthien, Idril and Arwen, who makes the sacrifice to, respectively, Beren, Tuor and Aragorn. In this story, however, Aegnor, the male Elf, refuses to make that sacrifice, partly, perhaps, because to do so would compromise his position as a prince and warrior of the Eldar.

The relation between Men and Elves is also a class relation. Like Tolkien himself — who although middle-class in education and manners came from a relatively impoverished background once his father died early and even moreso after his mother followed him — Beren, Tuor and Aragorn (all of whom, although of noble lineage, are exiled wanderers when they meet their future wives) could, as it were, marry above them to the daughters of Thingol, Turgon and Elrond; but Aegnor, as a prince of the Noldor, could not marry below him to Andreth, the daughter of a mere chieftain of Men.

It’s also worth noting that, while Aegnor, following the custom of the Eldar, would not marry while they were at war, Tolkien, like many young men going to the Great War, married Edith before he left for the front (something the execrable and inaccurate biographical film, Tolkien, changed). Given his chances of survival, he thereby risked making her a widow for the rest of her life, a fate equivalent to that of Andreth had Aegnor married her. It’s hard not to hear in this debate Tolkien reflecting on his own decision to expose his beloved Edith to the same fate. Of course, like Beren, Tolkien returned from the dead and lived with Edith their brief mortal lives, before ascending into their Catholic heaven within a year of each other. I hope Illuvatar granted them the happiness they deserved!

26. I imagine Tolkien didn’t mention the presence of the Ringwraiths at the Battle of Dagorlad at the end of the Second Age because of an inconsistency in the story. In the letter to Mrs. Eileen Elgar, Tolkien speculated about what would have happened had Frodo, after placing the Ring on his finger in Mount Doom (at the end of the Third Age), had proclaimed himself a new Dark Lord, and how long it would have taken him to gain mastery over the Ring and, crucially, the eight remaining Ringwraiths. Saruman himself, in ‘The Hunt for the Ring’ from Unfinished Tales, tells the Witch-King that, if he had the Ring, the Nine would bow down and call him Master. One of the never-stated fears of Sauron must have been that one of his enemies with the strength to do so — Saruman, Gandalf, Galadriel, Elrond, Glorfindel, Denethor or Aragorn — claiming the Ring, would also take control of the Nine, which would completely mess up his command structure. So when Isildur claimed the Ring as his own, he would also have had mastery over the Nine. Perhaps the only caveat to this is that, in the scroll discovered by Gandalf in the libraries of Gondor, Isildur said that he didn’t have the strength to master the Ring, and that he bore it with great pain. But that contradicts what Tolkien wrote about Frodo taking time to master the Ring and the Ringwraiths, and that Sauron would have to send different servants to take it back. Frodo had certainly attained great strength of mind through his sufferings, but was he of greater stature than Isildur?

But it’s an interesting observation that the Nine are missing from the account of the War of the Last Alliance and the Battle of Dagorlad. Of course, faced with so many great Elf Lords, the Nine might not have been up for the fight, and were leading, as it were, from behind, much like the British Generals in the Great War of 1914-18. During the Battle of the Pelennor Fields, Denethor tells Pippin how Sauron drives his slaves before him, wasting even his lieutenants (including the Witch-King), rather than exposing himself. This sounds like Tolkien’s comment on his own experiences in the trenches, and the cowardice and tyranny of leaders like Field Marshal Douglas Hague, who was known to the Tommies (i.e. Sam and footsoldiers like him) as the ‘Butcher of the Somme’ for the two million men who were killed and died under his command. The Ringwraiths are less generals, I think, than Cabinet Ministers, experts in intrigue, organisation and manipulation but with no courage for battle, driving the troops on with threats and punishments rather than leading them with courage and charisma, as Gandalf and Aragorn do. I think, when considering Tolkien’s numerous descriptions of war, that we should always see them through the prism of his experience of the Great War. Indeed, much of his writing can be considered as Tolkien’s commentary on the Great War, the watershed of European civilisation since the Renaissance.

27. If I remember correctly, the Ents wanted to remain nomadic, wandering in the continuous woodlands of Fangorn, Lindon and Mirkwood, while the Entwives fell in love with growing things in the fields south of Mirkwood that Sauron subsequently turned into the Brown Lands. Given that it was more likely that women, as gatherers, would have discovered the secrets of agriculture than men, who were out hunting, this split between Ents and Entwives sounds like a mythological representation of the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural and animal-husbandry societies in the Neolithic. As for the fate of the Entwives, Tolkien suggests that they ended up just south of the Shire. Sam’s report of an elm tree ‘walking seven yards to a stride’ in the Southfarthing, and Treebeard’s reminder to the Hobbits, at their parting, to look out for the Entwives on their return, suggests a few were still cultivating the earth on the borders of the fertile lands of the Shire. The obvious person to ask would be Tom Bombadil, though of course he’d never give you a straight answer.

28. I’ve been re-reading ‘The Bridge of Khazad-dum’, and there are several references in the Chamber of Mazarbul scene to ‘a deep voice raised in command’, directing the attack of the orcs in the corridor outside. It’s not the red-tongued orc-chieftain that Aragorn kills, or the cave troll. So it can only be the Balrog. Jackson’s first film has a magnificent realisation of this largely undescribed demon, but a Balrog, we know from the combat with Glorfindel after the sack of Gondolin (Lost Tales), is ‘double the stature’ of an elf or man, or even, in the first draft of this chapter in The Lord of the Rings, ‘no more than man-high’. In any case, a Balrog is not this giant-sized creature; and as this passage confirms, a Balrog speaks (just as Dragons do), doesn’t roar like a beast. A lot of Jackson’s image of the Balrog comes from the confusion, among early readers of the book (myself included), about how to pronounce the word, which we equated with a ‘bull’, hence the horns that almost all images of the Balrog retain. But they aren’t bulls and they don’t have horns (‘bal’ is Sindarin for power or might), or wings, except metaphorical wings of shadow. It’s still a brilliant film sequence, though.

29. I wasn’t aware of the tale of Tar-Elmar, having somehow missed it at the very end of the very last of the twelve volumes of The History of Middle Earth. But the ‘unfinished tale’ of Tar-Elmar is unique in telling what it was like to be on the other side of Númenórean empire building, a bit like listening to the Vietnamese or Iraqis or Afghanis or any of the other peoples of the numerous lands invaded by the US Empire on the justification of spreading ‘democracy’. I think this was a strong theme in Tolkien’s later work, as he watched the victory of the Second World War turn into US imperialism. It’s also something the corporate propagandists who attempted to desecrate his legacy with The Rings of Power could have addressed if they had really wanted to ‘diversify’ Tolkien.

30. Tolkien may have been the father of ‘fantasy’ fiction, much as Led Zeppelin were the fathers of ‘heavy-metal’ music; but just as Led Zeppelin wasn’t a metal band (Blues and Rock ‘n’ roll), Tolkien didn’t write fantasy. In fact, I don’t recall him ever using the term, which I’d imagine he’d associate with the top shelves of Soho bookshops (not that he’d ever visit). The terms Tolkien used to describe his secondary world were ‘fairy story’ — which in probably his most sustained essay (‘On Fairy Stories’) he defends from the accusation of ‘escapism’ — and ‘myth’. I haven’t read enough fantasy fiction (the first volumes of, respectively, Dune, The Stones of Shannara and A Tale of Ice and Fire) to comment authoritatively, but I’d imagine it is this that distinguishes Tolkien’s books from fantasy fiction, which is not mythical and appears to be escapist when it is not indoctrinating readers into the morality of corporate America. As to the importance and legacy of Tolkien’s work, the fact it is now under sustained attack by the ideologues and institutions of woke, in which the excremental The Rings of Power is the equivalent of Grond at the gates of Minas Tirith and The Tolkien Society the equivalent of treacherous Saruman, is perhaps the greatest testament to its lasting value. May the Valar turn them aside!

31. Tolkien is quite cruel towards the doomed Boromir, but there’s a reason for this. I’m re-reading The Lord of the Rings, and there are few if any times when Boromir opens his mouth without displaying his arrogance and immaturity, from his comments at ‘The Council of Elrond’ to his boasting on the pass over Caradhras to his hostile attitude to the Elves in Lothlorien. I’m always struck that, even after months of travel and shared perils, Boromir reports that the orcs at Parth Galen have taken ‘the halflings’, not Merry and Pippin, adding to Aragorn’s doubts about what to do next. By contrast, Aragorn and the Hobbits quickly develop a warm and even familiar intimacy, expressed in their slightly annoying habit of continuing to call him ‘Strider’, which Aragorn describes at ‘The Council of Elrond’ as a ‘scornful’ name.