On 20 May, 2015, the following text appeared on the website of Architects for Social Housing under the title ‘Manifesto’:

‘Architects for Social Housing (ASH) was founded in March 2015 in order to respond architecturally to London’s housing “crisis”. We are a Community Interest Company that organises working collectives of architects, engineers, quantity surveyors, urban designers, film-makers, photographers, researchers and housing campaigners for individual projects. Tailored to meet specific needs, these collectives operate with developing ideas under set principles.

‘First among these is the conviction that increasing the housing capacity on existing council housing estates, rather than redeveloping them as properties for capital investment, is a more sustainable solution to London’s housing needs than the demolition of the city’s social housing during a crisis of housing affordability, enabling, as it does, the continued existence of the communities they house.

‘ASH offers support, advice and expertise to residents who feel their interests and voices are increasingly marginalised by local councils or housing associations during the so-called “regeneration” process. Our primary responsibility is to existing residents — tenants and leaseholders alike; but we are also committed to finding socially beneficial, financially viable and environmentally sustainable alternatives to estate demolition that are in the interests of the wider London community.

‘ASH operates on three levels of activity: Architecture, Community and Propaganda.

-

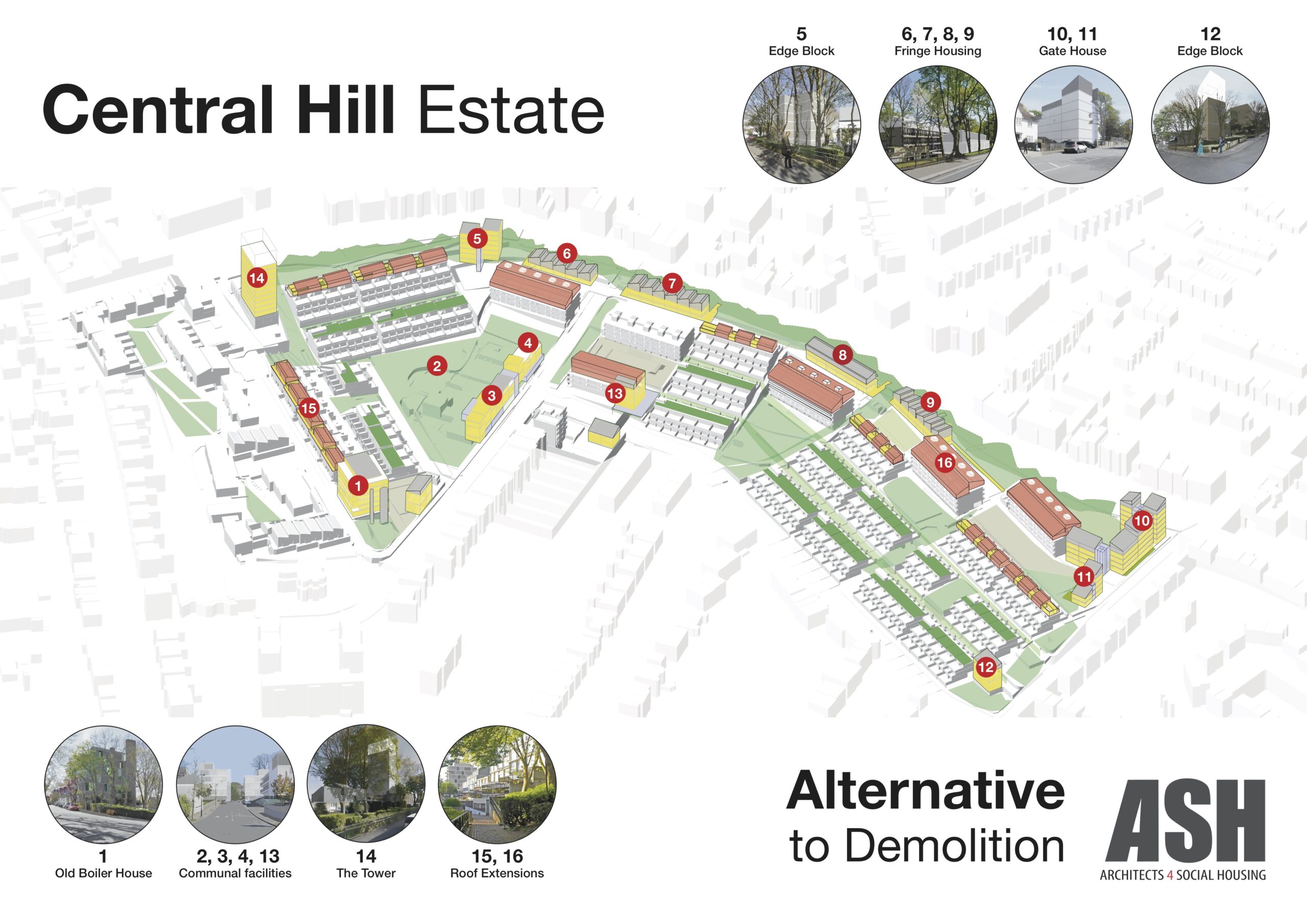

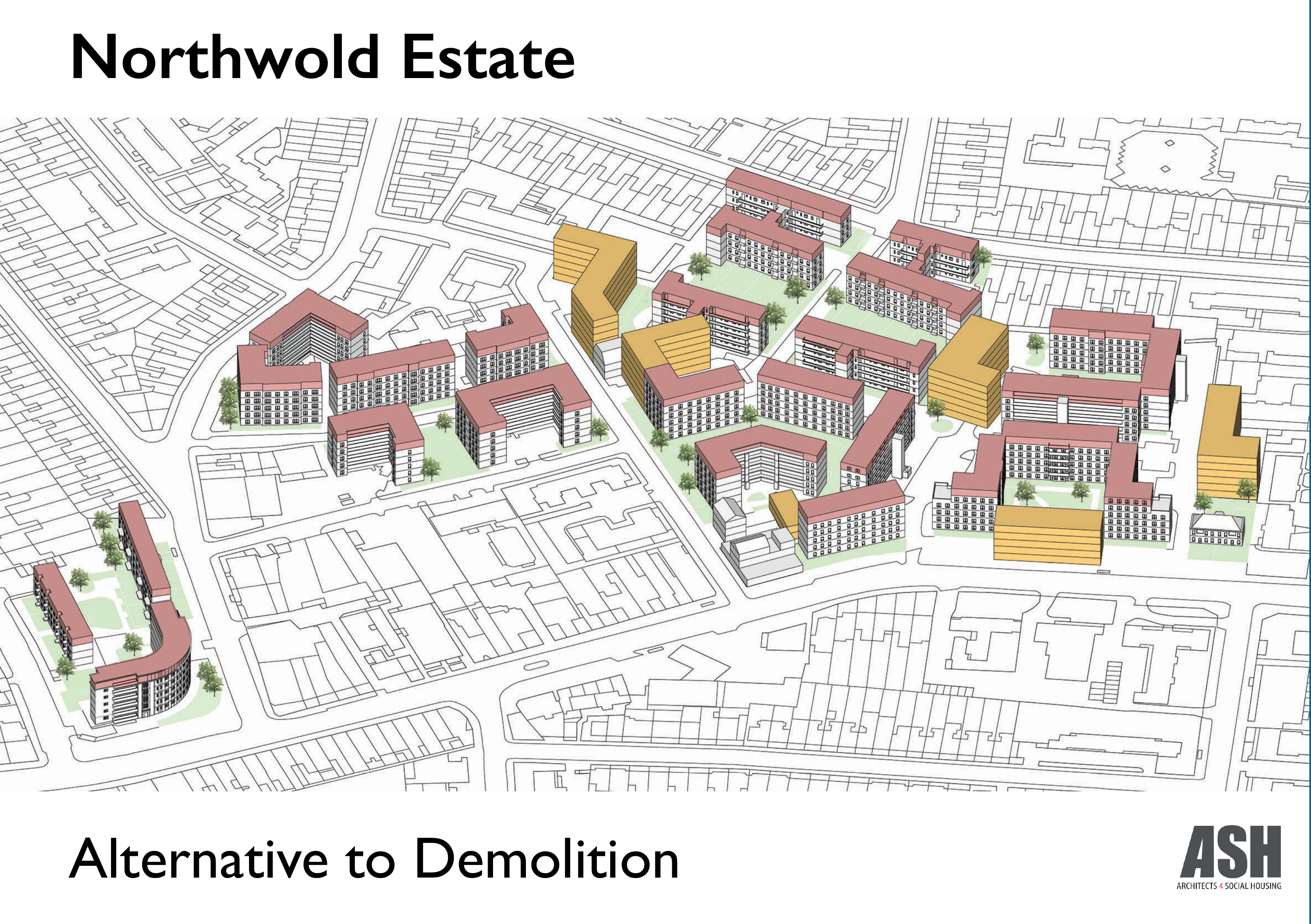

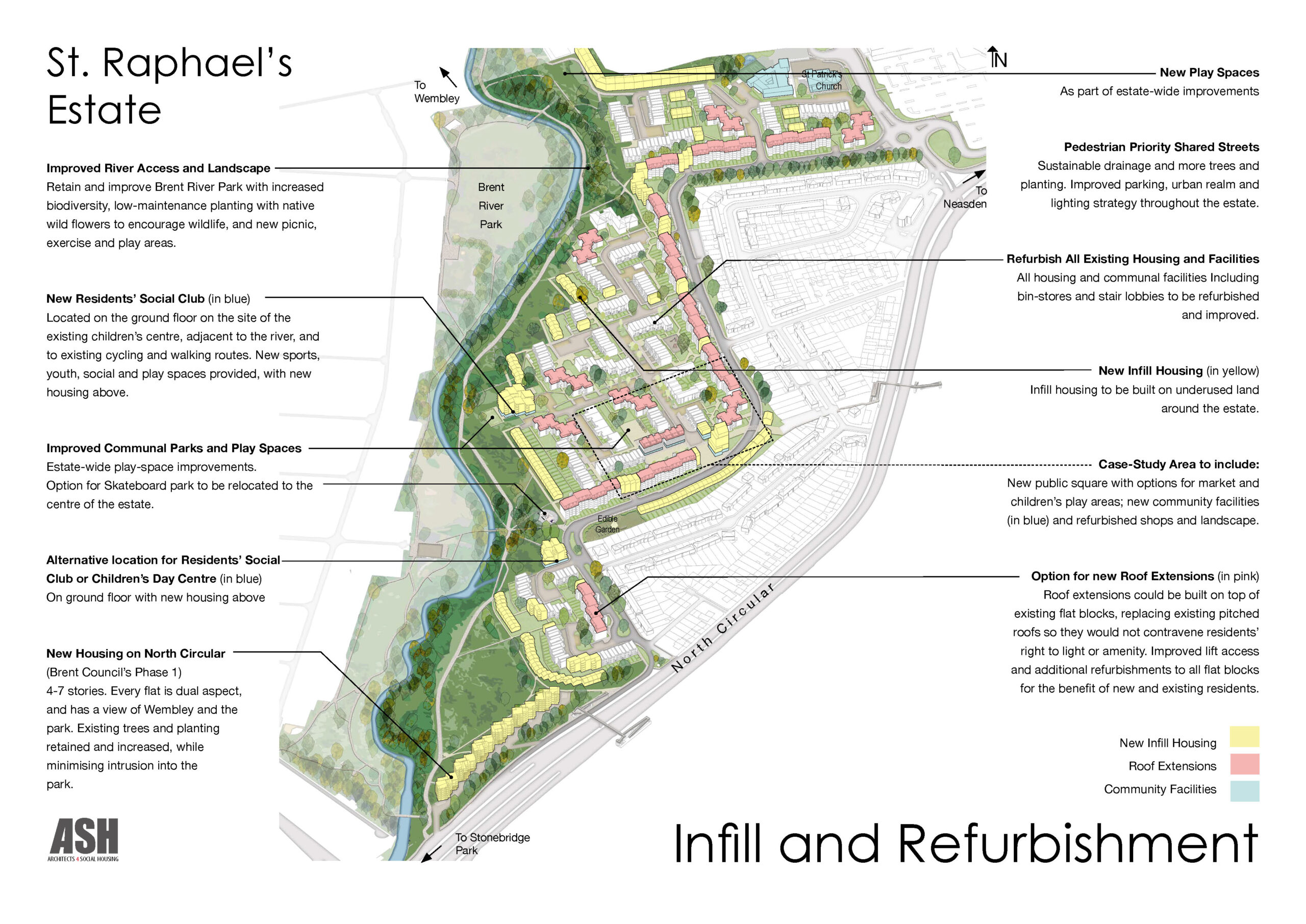

- ‘We propose architectural alternatives to estate demolition schemes through designs and feasibility studies for infill housing and lightweight roof extensions that increase housing capacity on the estates by around 50 percent and, by selling a proportion of the new homes on the private market, generate the funds to improve the communal facilities and refurbish the existing council homes, while leaving the communities they currently house intact.

- ‘We support estate communities in their resistance to the demolition of their homes by working with residents over a period of time, providing them information about estate regeneration and housing policy from a reservoir of knowledge and tactics pooled from similar campaigns across London.

- ‘We share research that aims to correct inaccurate statements and counter negative perceptions about social housing in the minds of the public, and raise awareness of the role of relevant interest groups — including political parties, local authorities, housing associations, property developers, real estate firms, architectural practices and other consultants — in the ‘regeneration’ process. Using a variety of means, including publications, presentations, reports, case studies, exhibitions, films and protests, we aim to initiate policy change within UK housing.

‘Whether you are facing the regeneration of your estate and in need of advice, or whether you want to offer your skills, expertise and time to our many projects, please get in contact.’

In fact, the original text of the ‘Manifesto’ was slightly different to this, as we amended it many times over the subsequent years. For example, ASH, which had been founded by the architect, Geraldine Dening, and myself, only became a Community Interest Company in September 2016; the percentage increase in housing we could add to estates was only established by our design proposals; and our emphasis on environmental sustainability came out of the lack of response to the social and economic costs of demolition from the architectural profession; but the gist of the text was the same.

Over the next seven years, ASH’s architectural work would not be limited to housing estates under threat of demolition, and we produced feasibility studies for the Patmore estate Co-operative, the Brixton Housing Co-operative, the Drive Housing Co-operative, the Brixton Gardens Community Land Trust, as well as visualisations for the Waltham Forest Civic Society. But our focus was on proposing design alternatives to the UK’s misnamed estate regeneration programme. Initiated in its current form in 1997 by the New Labour Government of Tony Blair, and continued under successive UK governments, Labour, Coalition and Conservative, in London ‘regeneration’ invariably means the demolition of the estate and its redevelopment as market-sale properties, with catastrophic consequences for the former council residents.

By the time we drew the work of ASH to an unofficial close in the summer of 2022, we had published some 200 articles, presentations and case studies on our website, and these had been visited over 230,000 times by 127,000 people from 179 countries. We had published 8 book-length reports, delivered more than 50 presentations to academic, art, design and architectural institutions, local authorities and the Greater London Authority; as well as giving hundreds of talks and interviews to campaign groups, journalists and students. We had held public meetings and hustings on subjects from the causes of the Grenfell Tower fire (July 2017) to changing policy on estate regeneration (June 2018). We exhibited at the Peer Gallery (2015), the Cubitt Gallery (2016), the Institute of Contemporary Arts (2017) and the Serpentine Gallery (2019). In the summer of 2019 we had a month’s residency at the 221A gallery in Vancouver, Canada, where we delivered a series of four lectures that we later published as a book, For a Socialist Architecture: Under Capitalism (2021). ASH’s work was the subject of a feature-length film, Concrete Soldiers (2017), and we appeared in the documentaries Dispossession: The Great Social Housing Swindle (2017) and What Went Wrong? Countdown to Disaster: Grenfell Tower Fire (2019). We also appeared numerous times as expert commentators on various news outlets, including RT UK News (although these were all removed when Ofcom revoked its UK licence in July 2022), Channel 4 News, Channel 5, ABC News and LBC Radio.

Most importantly of all, under our lead architect, Geraldine Dening, ASH produced design alternatives to the demolition of six London housing estates, including Knight’s Walk in Lambeth (2015), where we succeeded in stopping the demolition of half the homes; the West Kensington and Gibbs Green estates in West Kensington (2015-16), where our feasibility study, submitted as part of the residents’ Right to Transfer, helped save both estates from demolition; the Central Hill estate in Crystal Palace (2015-17); for which we produced a book-length case study, and at the time of writing the estate still stands; the Northwold estate in Hackney (2017), where our designs helped saved the estate from demolition; the Patmore estate in Wandsworth (2017-19), for which we produced a design vision of its future; and St. Raphael’s estate in Brent (2019-22), where our designs, again, helped save the estate from demolition. Through our design and community work, we estimate that ASH helped save 2,589 dwellings and (at an average of 2.7 people per home) the homes of around 7,000 residents from demolition by estate ‘regeneration’ schemes.

Our decision to pause ASH’s activities, therefore, might appear like a strange one; but it was occasioned by the response to our final study, Saving St. Raphael’s Estate: The Alternative to Demolition. In many ways the culmination of our design work, this had been produced by an 18-strong team of architects, architectural assistants, landscape architects, quantity surveyors, environmental and structural engineers, builders and researchers. Published in April 2022 with endorsements from a dozen architects and senior academics at some of the most eminent universities in the UK, we sent this book out to 160 of the individuals and institutions we thought might and should be interested in changing housing policy and practice in the UK and in particular in London, where ASH was based. These included Government departments, secretaries, ministers, agencies, boards, spokesmen and regulators; Greater London Authority boards, committees and panels; all 32 local authorities in Greater London plus the City of London; 27 non-governmental organisations; 19 housing associations; 32 architectural practices; 7 building industry professionals; 8 academic institutions, and 24 newspapers and journals. We didn’t bother sending our report to any developers, as these have neither an interest nor an obligation to change anything about the crisis that had accrued them such vast profits.

In response, we received nothing — not an email of acknowledgment, and not a single invitation to take up our offer to speak to their organisation about the findings from our book. It was at this point we realised that, after seven years of work, ASH had hit a brick wall. This book is partly about why we had. The short explanation, however, is that the individuals and organisations to which we had written had and have no interest in our alternatives to estate demolition and its contribution to the housing crisis, and were, to the contrary, interested in continuing, expanding and increasing the severity of this crisis. This book will explain why.

When ASH first came up with design alternatives to the demolition of council estates that were evidently and demonstrably socially beneficial, economically viable and environmentally sustainable, they were rejected outright by the councils implementing the demolition schemes, which were all run by Labour majorities. Not only that, but we soon found ourselves targeted as an organisation and as individuals by the Labour Party and its myriad subsidiaries. These included not just Labour councillors and members of the London Assembly, but also Labour activists, whom we came to realise exerted considerable control over what at the time was called the ‘housing movement’. In addition, after initially being welcomed as something of a much-needed social conscience to the poor reputation of architects, the architectural profession and its journals soon turned on us too. Eventually, so aggressive and destructive became this campaign that we were forced to close our social media accounts, which became platforms for online trolls sent to slander us. Worse, every time we were invited to speak at an event on the housing crisis, the organisers were similarly targeted until they relented and, as often as not, removed us from the list of speakers.

This campaign was partly a product of the messianic hysteria that surrounded the unlikely election of Jeremy Corbyn as Leader of the Labour Party in September 2015, 6 months after we had founded ASH. Indeed, the history of ASH in many ways parallels that of Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party, which ended in April 2020, a month into lockdown, and his failure to bring it into line with his professed socialist principles. What we found, instead, is that the Labour Party, London’s Labour Mayor (who had been elected in May 2016), and the Labour-run councils that dominated London then as now (21 of the 32 boroughs), were all more than happy to sacrifice the overwhelmingly working-class residents of council estates and collaborate with predatory developers if it gave them a chance at electoral power. And the Labour activists masquerading as housing campaigners worked actively to subordinate any and every resident campaign to save their homes from demolition to the electoral ambitions of the Labour Party. That meant relentless attacks on any organisation, including but not limited to ASH, that was not affiliated to the Labour Party and obedient to its commands. The result of this unofficial policy was that, across London, in the Labour-run boroughs in which the estate demolition programme was most widely implemented, residents were bullied into voting for the party whose councils were demolishing their homes and destroying their communities in the belief that, once Corbyn was elected Prime Minister, their estates would be saved.

I won’t go into the details of how this was done, which has perhaps become more familiar to the general public since March 2020 and the normalisation of the culture of slander, cancellation and no-platforming by which the UK public is bullied into compliance with the latest ‘crisis’ event; but I cite it here as one of the ways that those who profit from the housing crisis control how it is written about, and to whom and what it is attributed. What ASH quickly learned, and to our cost, is that this control is not limited to the investors, developers, builders, estate agents, housing associations, governments, municipal authorities and councils collectively responsible for implementing the housing crisis, but included, also, the individuals and groups who present themselves, under numerous self-designated ‘grass-roots’ organisations, as housing activists opposed to that crisis. Indeed, as equivalent corporate-funded organisations like Black Lives Matter, Extinction Rebellion and Just Stop Oil have subsequently demonstrated in relation to equally manufactured ‘crises’ today, control over public discourse, rather than giving voice to the silenced majority, is the primary role of activist organisations. At the time, these included the Radical Housing Network, Defend Council Housing, the Socialist Workers Party, the People’s Assembly Against Austerity, the Radical Assembly and Corbyn’s personal bodyguard, Momentum. Some of this very unpleasant story comes through in the articles I have reprinted in this collection, and perhaps one day the full story of ASH will be told; but that is not the subject of this book.

• • •

This book, which collects the most important articles that I, in my capacity as Head of Research for ASH, published on this subject, is about the UK housing crisis and the role of estate demolition schemes in reproducing it. Faced with the opposition to our proposals, it quickly became apparent that my role in ASH, as a non-architect, was to analyse the reason why. That meant reading and elucidating the often-impenetrable prose in which housing legislation is written; demonstrating what housing policy would mean in practice; exposing the economic motivations of its implementation and how these were realised; and documenting its effects not only on housing estate communities but on housing provision and affordability in the UK. This role made ASH unique, to my knowledge, among architectural practices, and gave our proposals, both architectural and policy-related, a weight and authority each would not have had on their own.

Published between October 2015 and November 2019 on the website of Architects for Social Housing, the articles collected in this book analyse the financing, legislation and policy behind the UK housing crisis, as well as the resistance to it. Their focus is the housing crisis in London, where wealth and poverty meet as nowhere else in the UK, and where the housing crisis, therefore, is most acute; but beyond that they look at the whole of the UK, to which housing poverty, precarity and homelessness is being exported on the London model. This makes these articles relevant beyond the London context, and even, hopefully, of use to those trying to understand the causes of the housing crisis in their own countries.

For the housing crisis was and remains a global phenomenon. Explanations of this crisis, therefore, which attribute it to local, municipal or national conditions, are fundamentally flawed. These latter include that certain cities are insufficiently dense and require the demolition and densification of their public housing; or that an influx of immigrants has placed a greater burden on the housing stock; or that bureaucratic red tape is stopping property developers from building the homes we need; or that there is insufficient land freed up by planning permission on which to build. These explanations are variously applied to cities with as different populations, economies, urban topographies, housing typologies and policies as London and Hong Kong, Berlin and Vancouver, Melbourne and São Paulo. As this book will argue, these are all incorrect in their assumptions, and, indeed, deliberately obfuscate the actual causes of the global housing crisis. The basic premise of this book, drawn from ASH’s seven years of work, is that the housing crisis is not a product of the failure of housing legislation and policy to house its citizens in safe, secure and affordable housing but, to the contrary, of the success of that legislation and policy in creating the conditions that produce the vast profits extracted from this crisis at every level of its production. The housing crisis, in other words, has been deliberately and carefully created. This book is about how and why.

As a collection of articles written over five years, it is also a record of how ASH discovered this seemingly paradoxical truth, which is not to be found, to my knowledge, in the numerous scholarly studies on the housing crisis written by academics who have never been near a council estate, but was produced by us through our practice working with estate communities to save their homes. Since this knowledge was produced incrementally, I have printed these articles largely, although not entirely, in their chronological order. They document, therefore, our first interventions in the housing movement in London, which at the time had formed around resistance to the estate regeneration programme; through the conclusions we drew from this about the causes of the crisis of housing affordability in the UK; to the increasingly detailed and investigative articles on the financing, legislation and policy driving that crisis, the devastating impact it was having on the British working class, and of the resistance to it, our own and that of other groups and residents not yet subordinated to the parliamentary aspirations of the Labour Party. There are numerous repetitions between these articles as this knowledge was acquired, but I have kept these here, not only because they bear repeating but because removing them would substantially change the articles.

This is not a hopeful book, therefore, and since we temporarily paused ASH’s activities in the UK, the housing crisis — which has been driven off the front pages of our press by a succession of other, equally manufactured crises — has only increased in severity. But in addition to the duplicities, deceptions, collaborations and betrayals that defined this period, something too of the excitement and comradeship of resistance also, I hope, comes through in these articles. Not every resident’s campaign of resistance we collaborated with was successful. Some, like Save Central Hill, after initial success, have found themselves targeted by councils and developers again. But what we came to designate as the ASH model of resistance, which delayed what would otherwise have been the summary process of consultation, demolition and eviction, cost the councils, housing associations and developers who sought to profit from the social cleansing of estate communities millions of pounds. It became a principal of our resistance that, notwithstanding the myriad excuses residents were given for the demolition of their homes and the destruction of their communities, the real motivation for estate regeneration is profit, and anything that could chip away at those profits would equally chip away at the motivation of those who stood to profit. To the achievements of ASH I listed above, therefore, must be added the financial loses we caused to the those who sought to dine on the carcass of the communities we helped save, even if these losses were accrued as profit by the lawyers, quantity surveyors, architects and other consultants they employed to overcome our resistance.

Finally, through our work ASH was able to contribute to changing housing policy. As I said, ASH’s practice is a unique combination of architectural design and analysis of legislation and policy. Together, this gave our practical proposals, whether that was design alternatives to the demolition of an estate or our alternatives to aspects of existing housing policy, stronger proof than if they had come from an academic study or architectural proposal alone. To promote our policy suggestions, we not only published articles, case studies and reports, but also delivered numerous papers and presentations; and, around local, municipal and national elections, we held hustings at which we sought to place housing policy at the heart of political debate, and tried to hold candidates to account for the housing policies of their parties.

Undoubtedly it has been forgotten, but when ASH began its practice, the idea of measuring the carbon cost of demolishing and rebuilding an estate versus its renovation and improvement was entirely new. Initially, it took us a while to explain to the environmental engineers who measured this cost for us why we had asked them to do it. And despite similar practices being used across the world, including in London, when we first suggested that, instead of demolishing them, we could build lightweight timber extensions on top of the existing council housing blocks, we were ridiculed by both councils and the architects they had employed to dismiss the threat this presented to the commissions they would earn from demolishing and redeveloping structurally sound buildings. And when we first targeted the architectural profession for its collaboration and complicity in estate demolition, exposing the cost to residents and the key role played by architects in the entirely duplicitous ‘consultation’ process, we were denounced as lacking in collegial loyalty to our fellow professionals.

A decade later, while municipalities, councils, developers and architects remain indifferent to the social and economic cost of demolishing the council homes of working-class residents and replacing them with properties for market sale, the environmental cost of doing so is now at the forefront of the regulation of the building industry. This, to be sure, is a double-edge sword, for fantastical claims about a ‘decarbonised’ future have been used to demolish council estates that, having been built in the 1960s and 1970s, don’t meet contemporary standards of thermal performance; but by drawing attention to the embodied carbon in an estate and the considerable waste incurred and pollution produced by demolishing it, we helped draw attention to one aspect — although not the most important — of the unsustainability of the estate regeneration programme.

Equally, by targeting architects employed in this programme at the prize ceremonies at which their complicity was rewarded, we oversaw a shift of opinion in the architectural press, if not necessarily the profession. This went from seeing such concerns as extraneous to the practice of architecture to something to which every architect and architectural journal is now expected at least to pay lip-service. This was largely short-lived, and as the annual jamborees of self-congratulation like the Stirling Prize have grown larger and wealthier, the main collaborators have drawn their wagons around the honeypot of estate demolition; but no-one in the architectural profession can any longer claim ignorance of the social and economic consequences of estate demolition for the people whose homes are demolished.

Through our analysis and criticisms of the succession of disastrous housing policies issued by the London Mayor, Sadiq Khan, we helped bring about changes to Greater London Authority policy to give residents a vote on the demolition of their estates. This, too, was a double-edged sword; and given the number of estates whose residents subsequently voted for demolition, raised questions about the transparency and probity of the consultation process and the promises residents are made about what will be built in their place. Finally, we contributed to the cessation of GLA funding for the replacement of homes for social rent that have been demolished as part of an estate regeneration scheme, and therefore helped reduce the profit motive for the developers behind such schemes.

More generally, through ASH’s costed design alternatives to the demolition of six London housing estates and our detailed analyses of what the social, economic and environmental costs of demolition would be to existing and future residents, we helped change the culture of the architectural profession, at least, away from demolition and redevelopment to making the retrofit of all existing housing, and not just council and housing association estates, the default option on any ‘regeneration’ scheme.

That said, and notwithstanding the local successes of ASH’s work, the crisis of housing affordability in the UK hasn’t improved and, indeed, continues to worsen. Some measure of this is the increase in the figures I quoted throughout these articles to the equivalent figures today, which corroborates the repeated warnings I issued in the 2010s of what was to come.

In 2015, when I wrote the first of these articles, the population of the UK was 65.12 million; ten years later, as I write this preface, it is projected to be 69.5 million in 2025, all of that increase coming from immigration. A quarter of that increase has been in London, the UK’s capital of immigration, where the population has risen from 8.86 million in 2015 to 9.84 million in 2025. Despite this increase in the demand for housing, the stock of local authority (council) housing in England has fallen from 1,643,262 in 2015 to 1,571,456 in 2022, a loss of nearly 72,000 council homes in a decade largely defined by the housing crisis. And despite the vast sums of public money used by successive UK governments to subsidise both the building and the buying of housing with billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money, the average price of a residential property in the UK in June 2015 was £272,000, and in June 2024 it was £288,000 — a reduction of £76,000 in today’s money when adjusted for inflation.[3] In June 2015, the average price of a residential property in London was £513,000; in August 2024 it was £531,000, a rather larger fall of £157,000 in today’s money. I would say, however, that this has more to do with the increasing unattractiveness of London and the UK in general as a place in which either to live or to invest, than with any change brought about by housing legislation.

Under the Right to Buy scheme, which was introduced by the Housing Act 1980 ostensibly to increase home ownership and in doing so has privatised over 2 million council homes, around 119,000 council homes were sold between 2015 and 2023, of which 109,000 are now being let out on the private rental market by buy-to-let landlords. As a direct result of this mass privatisation, the average rent on England’s private rental market was £948 per month in January 2015 and £1,576 per month in London; and in December 2024 it had risen marginally above inflation to £1,369 per month in England and £2,220 per month in London.

In addition to this sell-off of the UK’s public housing, in the 9 years between 2015 and 2024 some 38,393 homes for social rent, both local authority and housing association properties, have been demolished, overwhelmingly by the estate regeneration programme. In compensation for which, the total number of residential properties built in England in 2015 was 142,480, of which a mere 1,660 were built by local authorities; and eight years later, in 2023, that figure had only marginally increased to 161,800 residential properties, but of which, still, only 2,360 were built by local authorities. The remainder were built by private enterprises (123,600) and housing associations (35,860).

As an example of what this privatisation of housing provision has meant for the tenure of the properties being built, in the five years between 2017 and 2022 (the most recent data published by the Greater London Authority), the average number of residential properties approved by planning authorities in Greater London was 69,592 per year. Of these, 49,877 (72 percent) were designated as ‘market’, which means largely for market sale and then, under buy-to-let landlords, rented out on the private rental market; 8,479 (12 percent) were designated as ‘intermediate’, which means mostly for a variety of home-ownership schemes, including shared ownership, shared equity and rent-to-buy, as well as for intermediate rent; and, finally, 7,651 (9 percent) were designated as ‘low-cost rent’, which means for social rent and London affordable rent.

As a result of all this, in December 2016, an estimated 255,000 people were homeless in England; and by December 2024, eight years later, this number had risen to at least 354,000 people. In March 2015, there were 61,970 households living in temporary accommodation in England; in 2024 this figure had nearly doubled to 117,450 households, including 151,630 children. In 2015, 1.24 million households were on council housing waiting lists; in March 2024 it had risen to 1.33 million, and is predicted to pass 2 million by 2034. In London, there were 263,493 households on council housing waiting lists in 2015; and in 2025, despite local authority reductions in eligibility for such housing, there are 336,366 households. And despite the London Mayor promising, before his election to office in 2016, to build 50,000 new homes every year for the next decade, he hasn’t reached this figure even once, with the average number of dwellings completed 39,000 per year. Just 63.5 percent of adults in the UK’s supposedly ‘property-owning democracy’ owned their own home in 2015; and by March 2024 it had fallen to 50 percent of adults, 28 percent outright, 22 percent with a mortgage. Yet every parliamentary party’s housing policy is directed toward the chimera of home ownership, not the social housing so desperately and evidently needed. Having forced millions of residents onto the private rental market by these policies, the housing benefit bill in 2015/16 was £26 billion; and in 2025, despite all the changes and cuts to the benefits system, it is estimated to be £23.4 billion, largely because of the shortage of social housing and the consequent burden of paying ever higher market rents to private landlords.

As a further consequence, and the real success behind this decade of seemingly failed housing legislation and policy, in 2020/21, to take just one year, the Government spent £30.5 billion on housing; but only 12 percent of that was used to build or improve housing. The remaining 88 percent, £26.84 billion of taxpayer’s money, went into the pockets of private landlords as housing benefit. And as I said, that’s in just one year. Over the decade between 2013 and 2023, the Government’s Help to Buy equity loan scheme — another policy supposedly directed at home ownership — handed another £29 billion of taxpayers’ money to help purchase 340,000 properties, in the process further driving up the price of UK housing. Between 2015 and 2021, the Government has handed a further £20.7 billion to developers, housing associations and councils to build the myriad of tenure types under the deliberately misleading category of ‘affordable housing’ that is unaffordable to the mass of the population. Even with that caveat, between 2023 and 2026 the Government is predicted to spend five times more (£58.2 billion) on subsiding private landlords than on its entire affordable homes programme (£11.5 billion).

As a direct result of this public subsidy for private owners and property developers, the pre-tax profits of the four largest builders in the UK — Barret Developments, Taylor Wimpey, Persimmon Homes and the Berkeley Group — was £2.261 billion in 2015 (a more than fivefold increase from £416.9 million in 2011, when profits began to rise exponentially); yet in 2023, even after Brexit, two years of lockdown and the proxy-war in Russia, it was still £2.088 billion — though this is predicted to have declined to around £1.5 billion in 2024.

A further measure of how UK housing policy is directed toward increasing house prices and the value of property investments rather than reducing them, the estimated value of the housing stock in the UK in 2015 was £5.1 trillion, 63 percent of the UK’s entire net wealth of £8.1 trillion; and by 2024, after 10 years of housing legislation, the value of that stock had risen to £8.678 trillion, 71 percent of the UK’s net wealth of £12.2 trillion. With so much of the UK’s wealth invested in residential property, is it any wonder that legislation is directed to maintaining and increasing its value? This is especially true as the UK falls further into public debt brought about by successive Global Financial Crises, the first of which, in 2007, began as a housing crisis.

Housing legislation supposedly made into law to address the UK housing crisis over this decade included the Deregulation Act 2015; the Housing and Planning Act 2016; the Homelessness Reduction Act 2017; the Neighbourhood Planning Act 2017; the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018; the Tenant Fees Act 2019; the Affordable Housing Act 2021; the Building Safety Act 2022; the Leasehold Reform (Ground Rent) Act 2022; the Social Housing (Regulation) Act 2023; and the Leasehold and Freehold Reform Act 2024; as well as the numerous regulations amending earlier legislation. If their purpose was to provide the UK population with safe, healthy, habitable and secure housing in which we can afford to live and raise a family free of the greed of landlords and interest payments to banks, all this legislation has signally failed.

Perhaps the only aspect of the housing crisis that has improved is the fall in investment in UK property by companies registered in offshore financial jurisdictions. In 2016, there were more than 100,000 land titles in England and Wales registered to such companies. By 2022 this had risen to 138,000 properties; but following the sanctions against Russia this had fallen to 80,460 in 2023. And yet, in 2024 it was reported that 40 percent of the world’s dirty money is washed through the City of London and offshore financial jurisdictions like the Cayman and British Virgin Islands, and the vast majority of that is invested in property.

But as a result of this financialisation of the UK housing market, which has been invited and accommodated by housing legislation designed to inflate the value of UK residential property by making it a tax-haven for capital investment and the kind of financial speculation that created the US subprime mortgage crisis of 2007, in October 2015 some 600,179 residential properties in England were categorised as vacant, 203,596 of them as long-term (which means unoccupied and largely unfurnished for more than six months); and by October 2024, a decade later, this had increased to 719,470 vacant properties, 265,061 of them long-term.

All of which is to say, the crisis of housing affordability is not going away, is increasing in severity and reach, and will continue to force more and more people into housing poverty, precarity and homelessness. This alone would seem to corroborate my argument that the mass of housing legislation made into law, the housing policies imposed at every level of government, the practices of local authorities, housing associations and other landlords ostensibly to address this crisis, and the tens of billions of pounds of taxpayers’ money made available to councils, developers, builders, architects and investors, have not only done nothing to reduce the severity of the housing crisis but have, to the contrary, done the opposite, which is to maintain, increase and expand its reach.

The reasons for this haven’t substantially changed since 2015, although the 4 million immigrants who have settled in the UK over the past decade have further increased the burden on what little social housing the UK is building. To accommodate this influx, roughly 10 percent of the new affordable housing properties being built in England every year are going to tenants who were born abroad. As a result, in the 2021 Census, 20 percent of affordable housing in England had a head of household who was born overseas. In London, that figure more than doubles to 47.6 percent. An astonishing 10 percent of affordable housing in England and 17.5 percent of that in London had a head of household that had arrived here since 2021. Of the 793,000 residential properties for social rent in London in 2022, under the London Mayor some 377,000 had a head of household who was born in a foreign country, and 183,000, 23 percent, had a head of household who had entered the UK since 2021. Notwithstanding the burden this is placing on the UK taxpayer, the additional pressure immigration policy is placing on the UK’s social housing is as intentional as every other policy responsible for the housing crisis, and could be ameliorated by building the homes for social rent that remains the most in-demand tenure type of housing in the UK. This book is about why these homes aren’t being built, how UK housing legislation and policy is written not to meet housing need but to create it, and to what ends.

The reality is, homelessness is the threat and punishment that forces the working population into a lifetime of labour in order to pay off the loan on a sum of money the bank never paid them but merely purchased as a security when it issued them a mortgage on a property they will never own and whose price has been deliberately inflated for precisely this purpose. And that’s for the lucky ones. For the rest, which under 45 years of neoliberal housing policy is an expanding category of residents, the reward is to pay up to two-thirds of what’s left of their salary after government taxes in rent to a landlord who purchased the property with the help of government subsidies that were paid for with the taxes of their renters. Beneath this is the other expanding category of the homeless, who live in the growing number and forms of slum housing that is, perhaps, the most lucrative housing of all, and whose control over the lives of its residents is even greater than that of bankers and landlords over those of mortgagors and renters. It is for this reason that the so-called housing crisis, as I argue in this book, is not a crisis but one of the mechanisms by which finance capitalism accumulates greater wealth in the hands of finance capitalists while exercising greater control over those subjected to its mechanism. Indeed, it is for this reason that I spent seven years writing about this mechanism, and am spending several more making these articles available in book form at a time when the online world of digital texts is being subjected to greater censorship and control.

• • •

I said that ASH has drawn an unofficial and perhaps only temporary close to its activities in the UK; but that doesn’t mean we have stopped practicing. Confronted with corruption and a lack of political will for change at every level of the UK housing crisis, from its financing, legislation and policy to its implementation and even the supposed resistance to it, we moved to Hong Kong in 2024. Here, although under very different economic, geopolitical and policy conditions, there is also a housing crisis. But although we are new to all these, our sense is that the Hong Kong Housing Authority, while subject to similar financial pressures as London, unlike the Greater London Authority and its Mayor is genuinely trying to address the shortage, quality and affordability of housing for the residents of Hong Kong.

Crucial to this difference, it seems to me, is that, in Hong Kong, the Secretary for Housing, Winnie Ho, studied architecture at the University of Hong Kong and has 30 years’ experience as an architect in the Hong Kong Housing Authority. In the UK, in contrast, the latest Minister for Housing and Planning, Matthew Pennycook, studied international relations at the London School of Economics and has never had a job outside politics. As I show in this book, no matter which parliamentary party forms a government, UK housing policy is written by neoliberal think-tanks like Policy Exchange, Create Streets and the Institute for Public Policy Research and by estate agents like Savills, all of which have a financial interest in maintaining and expanding the crisis of housing affordability. When a Minister has no professional knowledge of his Ministry, as has been the case in the UK for as long as I can remember, and is in the job for a few months at most — and we have had fourteen such amateurs pass through this office over the past decade — he or she is in no position to question the policy recommendations of predatory professionals.

In the space of barely a year, ASH has already had a better response to our approaches from the housing authorities in Hong Kong than we had in seven years in London. Perhaps we will come to regret our present optimism, but when you work on the side of the working class pessimism is a class affectation of the politically compliant, and we have every hope of being able to influence policy on housing estate regeneration in Hong Kong for the better. That, however, is the subject of another book, which we will not be able to publish for several more years of practice and writing.

The Housing Crisis: Finance, Legislation, Policy, Resistance is the second volume in a new series titled the ASH Papers, which is collecting in book form the more important articles published on our website. The projected next two volumes will be titled, respectively, Case Studies in Estate Regeneration: Demolition, Privatisation and Social Cleansing, and Culture Wars: Art, Politics and Capitalism.

Simon Elmer is the author of The Housing Crisis: Finance, Legislation, Policy, Resistance (2025), from whose preface this article is taken. His recent books include Architecture is Always Political: A Communist History (2024), The Great Replacement: Conspiracy Theory or Immigration Policy? (2024), The Great Reset: Biopolitics for Stakeholder Capitalism (2023), The Road to Fascism: For a Critique of the Global Biosecurity State (2022), two collections of articles on the UK lockdown, Virtue and Terror (2020) and The New Normal (1920-21); and with Geraldine Dening, Saving St. Raphael’s Estate: The Alternative to Demolition (2022), For a Socialist Architecture: Under Socialism (2021) and Central Hill: A Case Study in Estate Regeneration (2018).

That was fascinating and moving. Thank you very much for the enlightening history of ASH and analysis of the housing crisis, which explanation reminds me of John Taylor Gatto’s analysis of education, in “Dumbing Us Down”, that it’s not failing at all, it’s doing exactly what it was set up to do, creating obedient citizens and compulsive consumers. Thank you very much for the work that you do. Best wishes.

LikeLike